Constitutional Vote In Chile Targeted By Coordinated Hashtag Campaign Before Election

Overview

A month after Chile erupted in violent, nationwide protests over chronic social and economic inequality in October 2019, its president and political parties negotiated a plan to end the crisis: The country would replace its 1980 constitution, written during Chile’s Pinochet dictatorship, with a new, more democratic constitution. They scheduled a referendum for the following year in which Chileans would decide whether to approve that plan. Soon afterward, a right-wing campaign began on , spreading hashtags that rejected the idea of a new constitution along with a torrent of misinformation about the October 2020 vote that left some Chileans confused about the goals of a new constitution – and the likelihood of it passing.

Background

In October 2019, Chile erupted in months of furious nationwide protest. Millions of Chileans took to the streets to demonstrate their anger over inequality and other social fractures in the South American country, long considered an oasis of stability in the region. The government of President Sebastián Piñera responded to these demonstrations with force.1 According to a February 2020 from the Chilean National Institute of Human Rights, 3,765 people were wounded during Chile’s demonstrations. Of those, 445 had eye injuries; 34 of them lost at least one of their eyes. Over 10,000 people were arrested.

Chile’s “estallido social”2 – or “social outburst,” as Chileans dubbed the protest movement – was in large part a reaction to how the country of 19 million was modelled during the right-wing military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990). Chile’s 1980 Constitution, written behind closed doors by Pinochet’s inner circle,3 established a free market economy based on U.S. neoliberal economic ideals, privatized social services like healthcare,4 labor rights,5 and education, and even commodified natural resources. As part of this constitution, Chile became, and remains, the first and only country in the world to privatize water.6 By late October 2019, Chilean protesters had coalesced around a demand to scrap that constitution entirely – one of the last remnants of Pinochet's dictatorship.7

On Nov. 15, 2019, a month after protests began, a wide spectrum of Chilean political parties in parliament came to an agreement with the president on a plan to address the crisis: The country would hold a constitutional convention, electing delegates from each party who would convene to draft a new constitution.8 A referendum, or popular vote, was called for April 26, 2020. It would ask Chilean voters to make a simple choice: a) “Approve” (Apruebo) or b) “Reject” (Rechazo) the drafting of a new constitution. If approved, this would be the first step in a years-long constitutional process.9

The Rechazo side’s electoral campaign was publicly helmed by several figures from the Chilean Republican Party, which represents the extreme of Chile’s right wing. Its two most visible faces were José Antonio Kast,10 controversial founder of the Republican Party, and Gonzalo de la Carrera,11 then a Republican mayoral candidate (now congressman-elect). The Apruebo electoral campaign was led by a leftist coalition of political parties.12

The response from Chilean voters to the referendum, which was later postponed to Oct. 25, 2020, because of the coronavirus pandemic, fell along partisan lines. Conservatives lined up behind the Rechazo vote, while progressives and many centrists fell into the Apruebo camp. Campaigning occurred on TV, at rallies and public meetings, in street demonstrations, which persisted in Chile for months after the referendum agreement, and online. In the lead up to the vote, both public protests and opinion polling indicated substantial popular support for “approving” the constitutional convention.13

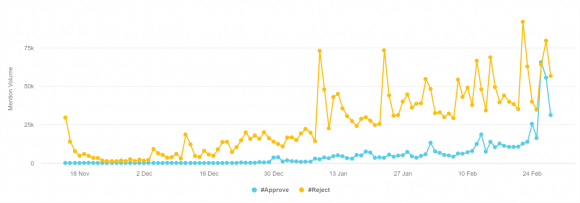

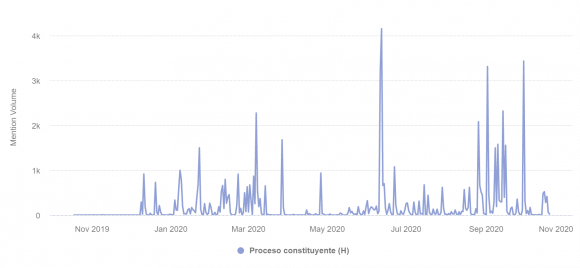

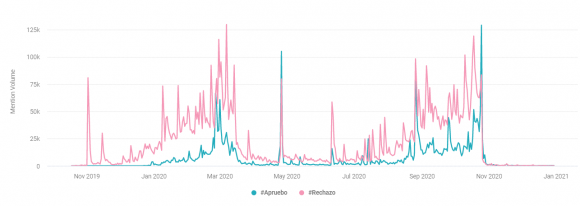

Online, however, the Rechazo option was far more prominent, according to our social media monitoring around Chile’s referendum process. Starting on the very day of the decision to hold the vote, on Nov. 15, 2019, tweets in support of Rechazo far outpaced those supporting Abruebo. On average, hundreds of daily tweets about Chile’s constitutional process mentioned “Apruebo” in November and December 2019, while an average of roughly 10,000 tweets a day on that topic mentioned “Rechazo.”

- 1 El Mostrador, “A 4 meses de inicio del estallido, INDH actualiza cifras de víctimas de violencia y alerta que persisten los casos de lesiones oculares,” El Mostrador, February 8 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/VT8Q-9R4D.

- 2 Amanda Taub, ‘‘Chile Woke Up’: Dictatorship’s Legacy of Inequality Triggers Mass Protests’, New York Times, November 3 2019, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/J7XL-FLPF.

- 3 Valdis, Juan Gabriel. Pinochet's Economists: The Chicago School in Chile (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

- 4 Elena S.Rotarou and Dikaios Sakellariou, “Neoliberal reforms in health systems and the construction of long-lasting inequalities in health care: A case study from Chile,” Health Policy, May 2017, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/ATW7-GR8H.

- 5 Paul W. Posner, “Labour market flexibility, employment and inequality: lessons from Chile”, New Political Economy, 2017, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/YR72-VJPC.

- 6 “ESTUDIO IDENTIFICA A CHILE COMO EL ÚNICO PAÍS CON EXPRESA PROPIEDAD PRIVADA DE DERECHOS DE AGUA,” Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, March 29 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/Q2EV-E49Y.

- 7 Claudia Heiss and Patricio Navia, “You Win Some, You Lose Some: Constitutional Reforms in Chile’s Transition to Democracy”, Latin American Politics and Society, 2007, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/7EMB-798J.

- 8 Jennifer M. Piscopo and Peter Siavelis, “Chile puts its constitution on the ballot after year of civil unrest,” The Conversation, October 20, 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/7L7N-EFJ9

- 9 “Chile puts its constitution on the ballot after year of civil unrest” The Conversation, October 20 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/N2GK-H68J.

- 10 Loreto Concha, José Antonio Kast y Plebiscito: “Es incompatible decirse de derecha y votar Apruebo (…) Esta vuelta de chaqueta, este camuflaje con la izquierda, nos tiene con un país más pobre, con más violencia, con más déficit fiscal y con más riesgo”, Duna FM 89.7, October 21 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/X7LF-FUBF.

- 11 “Realizan nueva manifestación a favor del Rechazo: Hubo críticas a Lavín y a la franja electoral”, CHV Noticias, September 26 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/68LM-MKEZ.

- 12 Carlos Reyes P., “Carteles, banderazos y videos: El despliegue por el Apruebo y el Rechazo en el primer día de campaña para el plebiscito del 25 de octubre”, 26 August 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/4BCW-9HQW.

- 13 El Mostrador, “Encuesta Agenda Criteria confirma que la mayoría de los electores de Piñera están por el Apruebo,” September 3 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/DX6J-HXJD.

The already large gap on Twitter representations of the two sides expanded dramatically in January 2020, with “Rechazo” mentions rising to roughly 50,000 daily, compared with approximately 2,000 or 3,000 mentions of “Apruebo.” This discrepancy persisted, almost without exception, until the day of the vote on Oct. 25, 2020, in which the Apruebo side handily triumphed.

This disproportionate online activity promoting Rechazo in 2020 was the result of a coordinated media manipulation campaign that flooded Twitter with messages and hashtags attacking Chile's constitutional convention and sometimes spreading false claims about its alleged consequences for the country. This, in turn, dictated the Twitter trending topics in Chile, led misinformation to spread across other platforms with broader reach in Chile, like WhatsApp and , and may have influenced the traditional media’s coverage of the upcoming referendum.1

All this distorted the reality of what was truly happening in the country, which was a groundswell of support for a new constitution.

This case study documents the far right’s digital campaign against Chile’s 2020 constitutional assembly. It is based on analysis using the social media monitoring tool Brandwatch Analytics of more than 18 million pieces of internet content, namely Twitter posts and web publications, internet forums, and .

- 1 Shannon C McGregor and Logan Molyneux “Twitter’s influence on news judgment: An experiment among journalists,” Journalism, October 5 2018, Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/K7Z2-CCA9

Stage 1: Manipulation campaign planning and origins

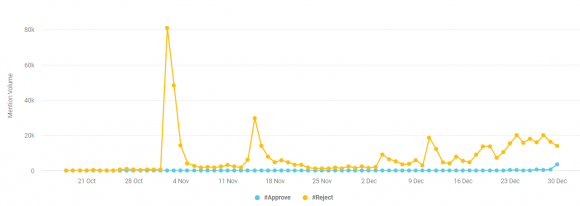

The first signs of a media manipulation campaign in Chile’s constitutional process came in November 2019. On Nov. 2, we observed a sharp spike in posts using the hashtag #noalaasambleaconstituyente (“no to the constituent assembly”), primarily among the leaders and supporters of Chile’s Republican Party. By the end of that day, 55% of the 187,380 total Twitter mentions of the constitutional convention used that one hashtag.

This date had no particular significance in the current political debate. On Nov. 2, 2019, politicians were still discussing how to address protesters’ demand to abolish the Chilean Constitution, with parties on the left pushing for a referendum and those on the right opposing the idea.

Despite right-wing opposition, Chile’s major political parties and President Piñera agreed on Nov. 15, 2019 to hold a constitutional convention. That day, another anti-referendum hashtag erupted on Twitter. This time, it adopted a catchphrase first used to rally Chilean voters in the 1989 plebiscite that ultimately ended Pinochet’s government: #vamosadecirqueno (“We will say no”). This was an example of viral sloganeering – a tactic of creating short, catchy phrases intended to deliver persuasive, disruptive messaging. Tweets using #vamosadecirqueno often also included #noalaasambleaconstituyente. As before, the accounts promoting these hashtags were primarily members and leaders of the Republican Party.1

Party founder Kast was top among those actively tweeting and retweeting both Rechazo hashtags. Kast openly celebrates Pinochet’s dictatorship. His firm stance against migration once led him to propose digging a trench along Chile’s northern border to keep migrants out, earning him comparisons to former US president Donald Trump and Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro. Another major amplifier of the #noalaasambleaconstituyente campaign on Twitter was Rojo Edwards, who at the time was Kast’s spokesman. He is now a Republican senator-elect.2

In 2017, Kast ran for president as a far-right fringe figure, and received some 8% of the vote. But in 2019 he attracted media attention and support on the right for leading the crusade against the protests and then the effort to rewrite Chile’s constitution. In 2021 Kast became a leading contender in the country’s presidential election; he finished first place in the initial round of the election in November, pitting him against the left-wing second-place finisher, Gabriel Boric, in Chile's Dec. 19, 2021, presidential runoff. 3

- 1 DiegoPatriota (@dgalarce), “Otros no caeremos en el jueguito marxista. La Constitución No Era tema en este gobierno. SEA LO QUE SEA QUE QUIERAN CAMBIAR #VamosADecirQueNO. 88% acá está indicando lo mismo,” Twitter, November 11 2019, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/7LTW-X6HQ.

- 2 “Rojo Edwards fue elegido senador por la Región Metropolitana,” 24 Horas, November 21 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/7PZN-6AYX.

- 3 Eduardo Thomson and Valentina Fuentes, “Chile’s Kast Beats Top Leftist Contenders in Presidential Poll,” Bloomberg, November 5 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/8ZAC-XTKN.

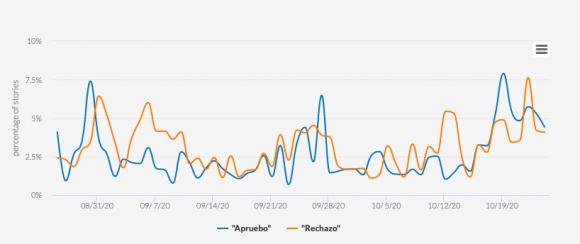

Figure 2. Total hashtags associated with the Apruebo and Rechazo campaigns (October - December 2020). Supporters of Chile’s constitutional convention were talking on Twitter, too, but their hashtags rarely saw sharp spikes like Rechazo’s did. Source: Brandwatch Analytics. Archived on perma.cc, https://perma.cc/VCL6-NZB8. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

These first two relatively short-lived Twitter hashtag campaigns set the groundwork for the central media manipulation campaign documented in this case study: the creation and use of the hashtag #YoRechazo in 2020 to oppose the referendum and spread misinformation.

Several groups of right-wing Twitter users came together in a networked faction to promote this campaign. One was a loose network of “patriot” Republican accounts on Twitter that had previously focused on attacking other high-profile social issues in Chile such as migration in 2018.1 For example, @DianaChehade, @_angelamo and @_cacotorres were active promoters of both anti-migration and anti-referendum chatter on Twitter, along with 833 other accounts that participated in both campaigns.

Other accounts promoting the Rechazo’s campaign message online were Twitter users already publicly identified as opposing the constitutional process, such as @FridaSiKahlo – a self-identified “anti-communist” – and @Coquiangelica, a nationalist, pro-life figure. But many participants in the early online activity decrying Chile’s constitutional assembly were small, and in some cases new, Twitter accounts that demonstrated irregular and coordinated activity.2 They used the same set of words to describe themselves in their Twitter bios: “patriota” (patriot), “anti-zurdos” (anti-leftist), or “pinochetista” (Pinochetist), and tweeted at extremely high volume, often posting hundreds of tweets a day. These accounts also had similar, and predictable, tweeting habits: The account they most retweeted was José Antonio Kast, and they interacted heavily with the Twitter user @Francis2583052, an anonymous account with 44.5K followers.

This online army of right-wing activists, newly created “patriot” accounts, and prominent Republican Party leaders would serve as the main network promoting the #YoRechazo campaign in the leadup to the October 2020 referendum.

We have no insight into the planning of this campaign, and cannot conclude who exactly was behind it. However, we know that the same far-right Chilean politicians who led the official Rechazo electoral campaign – Kast, de la Carrera, and Edwards – along with a handful of other prominent Republicans, were the most significant amplifiers of Rechazo’s online messages, too.

Notably, these influential Republicans were rarely the first accounts to tweet the hashtag. Instead, in a pattern we observed over months of social media monitoring, a Rechazo hashtag or message would originate with a seemingly random account promoting the Republican Party – often one of those small, new accounts with few followers. That tweet would quickly be retweeted by Kast, de la Carrera, Edwards or another Republican influencer online, resulting in it getting substantial pickup. This behavior distanced Republican politicians from the online manipulation campaign promoting their cause.

- 1Ignacio Loyla R., “La “post verdad” en redes sociales: ¿nos han hecho creer que los chilenos somos racistas?” CIPER, October 7 2018, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/L5VH-QGZ8.

- 2 Patricio Durán, Tomás Lawrence, and Juan Esteban Fernández, “La red social Twitter y el proceso constituyente: el caso de las cuentas anómalas”, Ciper, October 17 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/E3BN-LDHF.

Stage 2: Seeding the campaign across social platforms and web

As anti-referendum tweets continued to circulate1 in late 2019 and into early January 2020,2 they occasionally included the hashtag #YoRechazo3 – ”I reject.”

In January, that hashtag began to circulate more widely, specifically in reference to the referendum, initially rising on Jan. 64 with a handful of widely circulated Pro-Rechazo tweets including #YoRechazo.5 Then, on Jan. 8 at 8:37 a.m. an account presenting itself as affiliated with Republican Party supporters, @PRepublicanoCL, issued a call for a “megatuitazo” – which roughly translates to “mega tweetathon” – to be held at 7:00 pm that evening, to promote the hashtag #YoRechazo: “Let’s go Chilenos for that #Megatuitazo!,” said the post. “Today we’re revving our engines to support #YoRechazo !!”

The @PRepublicanosCL account is styled as if it were an official Republican Party Twitter account, featuring a profile picture of party leader Kast against a Chilean flag, but there is no evidence that it is. Nor does it have a large following: around 4,700, at the time of writing this case. We do not know who runs this account.

- 1 Regia Pam (@Regia_Pam), “Los orcos creen que con una nueva constitución se les arregla la vida. La izquierda jamás tendrá la estatura que merecen. Son delincuentes incendiarios, que han destruido y saqueado. No tienen dignidad. #RechazoNuevaConstitucion #YoRechazo @sebastianpinera,” Twitter, December 25 2019, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/MK3K-ANT9.

- 2AlePsx (@Ale_Astudillo), “Por fin una buena Noticia, se pusieron los pantalones Favor Difundir #SoyDeDerecha #YoRechazo @joseantoniokast @cata_1910 @VeronicG__ @2Iluminada @albertoplaza @tere_marinovic @chechohirane @carreragonzalo”, Twitter, January 6 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/6DGB-6FA6.

- 3 Ibid.

- 4 Ibid.

- 5 Elsa (@@ElsaBueno3), “Domingo 26 de abril votarás: #YoRechazo #RT,” Twitter, January 6 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/FSZ9-G35J.

Figure 3. Tweet from an account that presents itself as affiliated with the Chilean Republican Party calling their partisans to do a tweetathon using the hashtag #YoRechazo. The tweet reads, “Let’s go Chileans on this MEGATUITAZO!, today we’re revving our motors to support #YoRechazo !!” Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/KUT6-W36P. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

The megatuitazo call to action was retweeted only 297 times, with 13 quote tweets, but those retweeters include influential figures in online Chilean right-wing circles. The megatuitazo plan was retweeted, for example, by @CoquiAngelica, the account of Gloria Naveillan, a right-wing activist who is now a Republican congresswoman-elect; she has 35K followers. @Makeka, a pro-Pinochet blogger and one of the first participants in the early Rechazo hashtag campaigns, also retweeted the megatuitazo call-out to her 18.7K followers. Many other Republican Party partisans joined the campaign that day.

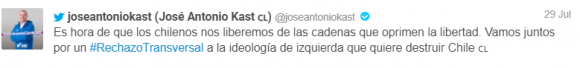

But by far the most influential participant in the megatuitazo, according to our analysis of Twitter data, was Kast. He tweeted1 or retweeted the hashtag #YoRechazo six times2 as part of the “megatuitazo” on Jan. 9, 2020, saying in one message, “We are the resistance, we are many, we are more.”3 That tweet received 9,505 likes and 4,077 retweets – more engagement than any other #YoRechazo tweet that day. Kast was also one of just three elected politicians – and the only one from his party – to promote #YoRechazo that day.

By the night of Jan. 9 there were 83,330 tweets using the hashtag #YoRechazo, and #YoRechazo was a Twitter trending topic in Chile. This is an example of a media manipulation tactic called “gaming an algorithm.”

The megatuitazo campaign, issued by an anonymous and relatively small Republican-identifying account,4 united opponents of Chile’s referendum behind a single slogan. Before Jan. 9, Chileans expressing their distaste for a new constitution used a variety of terms to convey that view, often simply the word “no.” After the successful Jan. 9 hashtag campaign, the Chilean right lined up behind the term “rechazo.”

The Rechazo campaign continued throughout 2020, with ebbs and flows, including other “tuitazos''– Tweetathons – that would lead to spikes in online activity. For example, on Aug. 26, after a Tuitazo, there were 97,035 mentions of Rechazo-related hashtags, compared to a rolling average of 25,604 daily over the week prior. The term “rechazo” was used in combination with many other words indicating opposition to the referendum. These included: #RechazoRetirodeFondos, #RechazoNuevaConstitución, #RechazoIzquierdaMiserable, #RechazoCrece, #RechazoSinMiedo, #Rechazoganasivotamos, #Rechazoganazapateando, #Rechazoeslibertad, #LaCalleRechaza, #RechazotuOportunismo, #RechazoEstafaConstituyente, among many others. Kast continued to be the most active promoter of such hashtags throughout 2020, according to our analysis of Twitter data

- 1 José Antonio Kast Rist (@joseantoniokast), “Somos la Resistencia. Somos muchos. Somos más. En silencio y con humildad. Sigamos trabajando por Chile! #YoRechazo,” Twitter, January 9 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/GJ2X-ZQYN.

- 2 José Antonio Kast Rist (@joseantoniokast), Twitter, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/2QHQ-SPN4.

- 3José Antonio Kast Rist (@joseantoniokast), “Somos la Resistencia. Somos muchos. Somos más. En silencio y con humildad. Sigamos trabajando por Chile! #YoRechazo,” Twitter, January 9 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/GJ2X-ZQYN.

- 4 Republicanos#AtréveteConKast (@PRepublicanoCL), “Vamos Chilenos por ese #MEGATUITAZO!, vamos hoy calentando motores apoyando #YoRechazo !!” Twitter, January 8th 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/T5XE-23S5.

Figure 4. Callis for a tuitazo (“tweetathon”) or megatuitazo (“mega tweetathon”) between Oct. 18, 2019 and Oct. 25, 2020. These calls all came from the #YoRechazo camp; #YoApruebo never held a tweetathon to promote its cause online. Source: Brandwatch Analytics. Archived on perma.cc, https://perma.cc/5FDW-KSUP. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

The second most engaged figure in the #YoRechazo online campaign, according to our research, was a Chilean economist and former Pinochet minister named Sergio Melnick. Melnick continuously spread the #YoRechazo hashtag throughout 2020, along with misinformation1 about Chile’s constitutional process.2 Between October 2019 and October 2020, Melnick insinuated 116 times, according to our Brandwatch analysis of Twitter, that scrapping the Pinochet-era constitution would turn Chile into either Venezuela or Cuba (a common scare tactic of the Latin American right,3 and a wedge issue in the region). To make this point clear, he frequently ended his tweets with the mash-up “Chilezuela.” 4

Among other right-wing figures who participated in the online anti-referendum campaign was congressional representative Sergio Bobadilla, who identified himself as “Congressman Rechazo” (for unknown reasons, he has since changed his Twitter handle from @Bobadillarecha1 to @dipuBobadilla).5 Bobadilla tweeted Rechazo hashtags 321 times from October 2019 to October 2020, and frequently promoted the false Chile-Venezuela connection.6

Rojo Edwards, then Kast’s spokesman, also played a key role in pushing many of the Rechazo hashtags. He also called for the referendum to be cancelled because of COVID;7 but in general we did not observe him pushing misinformation. Congressman-elect Gonzalo de la Carrera – a visible leader of Rechazo street marches, whose campaign slogan is “uniting the right” – and the libertarian columnist Teresa Marinovic were also influential campaign participants for Rechazo online, according to our analysis. Marinovic is now a member of the constituent assembly that will rewrite Chile’s constitution.

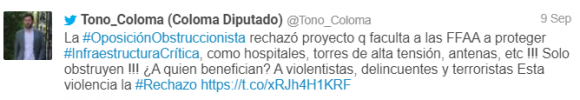

The main observable outcome of the Rechazo campaign strategy was political adoption of the concept “Rechazo” – rejection – by many far-right politicians. The hashtag #YoRechazo had occasionally been seen on Twitter in Chile in the months prior to the megatuitazo hashtag campaign. After Jan. 9, however, it became ubiquitous in right-wing political debate, and its usage broadened substantially to apply not only to the constitution but to many unrelated right-wing causes. The following tweets show the concept of “rejection” applied to everything from infrastructure to leftism.

- 1 Sergio I. Melnick (@melnicksergio), “Nueva trampa de la izquierda: El plebiscito tiene sólo dos opciones, rechazo y apruebo. Resulta que el rechazo recibe LA MITAD de financiamiento que el apruebo.. ¿es justo?....obviamente que no. La izquierda hace trampas #RECHAZO”, Twitter, September 9 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/P5LA-FGSP.

- 2 Sergio I. Melnick (@melnicksergio), “Para cambiar una constitución, el mínimo de participación es de 65% del padrón y con voto obligatorio por cierto,” Twitter, August 17 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/HJE3-MMQL.

- 3 Tom Phillips and Dom Phillips, “The new Venezuela? Brazil populist Bolsonaro's scare tactic gains traction,” The Guardian, October 11 2018, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/L7MB-VMVD

- 4 Sergio I. Melnick (@melnicksergio), “Con el actual defiit fiscal, el populismo, y la corrupción de instituciones claves... YA ESTAMOS. Con nueva constitución vamos a Chilezuela” Twitter, July 11 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/U23B-BQGC.

- 5 Diputado Sergio Bobadilla (@dipuBobadilla), “Sólo una cosa mas: Soy el #DiputadoDelRechazo Y trabajamos todos los días por el Chile grande y fuerte del #Rechazo Ya tuvimos miedo. Hoy rabia por ver como destruyen el país y por los abusos de los violentistas y sus defensores. Somos más. Si vas a votar #Rechazo ganamos,” Twitter, October 8 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/Q3GB-C3A6.

- 6 Diputado Sergio Bobadilla (@dipuBobadilla), “Ahora q todo el mundo sabe que el dictador Nicolás Maduro es un violador de los DDHH y un genocida q ha cometido crímenes contra la humanidad, el #Rechazo crece La izquierda chilena cumple la orden de Maduro: hacer constitución bolivariana Mejor #Rechaza. El #RechazoSalvaChile,” Twitter, September 16 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/Q3GB-C3A6.

- 7 Rojo Edwards Senador RM (@RojoEdwards), “Si se prohiben aglomeraciones de mas de 500 personas x #coronavirus, me imagino que por el mismo motivo se tendra que suspender el Plebiscito.#RechazoNuevaConstitución #coronaviruschile,” Twitter, March 13 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/G22W-DTWL.

Figure 5. Tweet from Chilean presidential candidate José Antonio Kasreading, “It’s time for Chileans to liberate ourselves from the chains that oppress liberty. Together let’s go for a #RechazoTransversal (“crosscutting rejection”) of the leftist ideology that wants to destroy Chile.” Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/QL4Q-MGCW. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

Figure 6. Tweet from then-Kast spokesman Rojo Edwards using the hashtag #RechazoRetiroDeFondos (“reject funds withdrawal”) to allege cronyism and political corruption in leftist Chilean politics. archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/PWV3-7V4P. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/PWV3-7V4P. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

Figure 7. Tweet by the right-wing Chilean congressman Antonio Coloma using the hashtag #Rechazo to attack his political opponents’ stance on infrastructure projects. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/SSU6-JKL9. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

Many tweets using the #YoRechazo hashtag also spread misinformation1 about the constituent process. One common example was the false claim that Chile’s new constitution would abolish the right of private property. During the Jan. 9 megatuitazo, this unfounded rumor – which previously2 had appeared sporadically online3 at low volume4 – was mentioned 1,755 times alongside the hashtag #YoRechazo. It later appeared in a TV ad for the Rechazo campaign5 (minute 4:09), paid for by the conservative foundation Ciudadanos por Chile. The private property false claim, an effort to connect the Chilean left with the socialist regime in Venezuela, proved resonant: It continued to spread on Twitter, Facebook, and Whatsapp up until the October 2020 plebiscite. After January 2020, tweets including the hashtag #YoRechazo frequently also included the words “Venezuela,” “Chilezuela,” “Maduro” or “Chávez.”

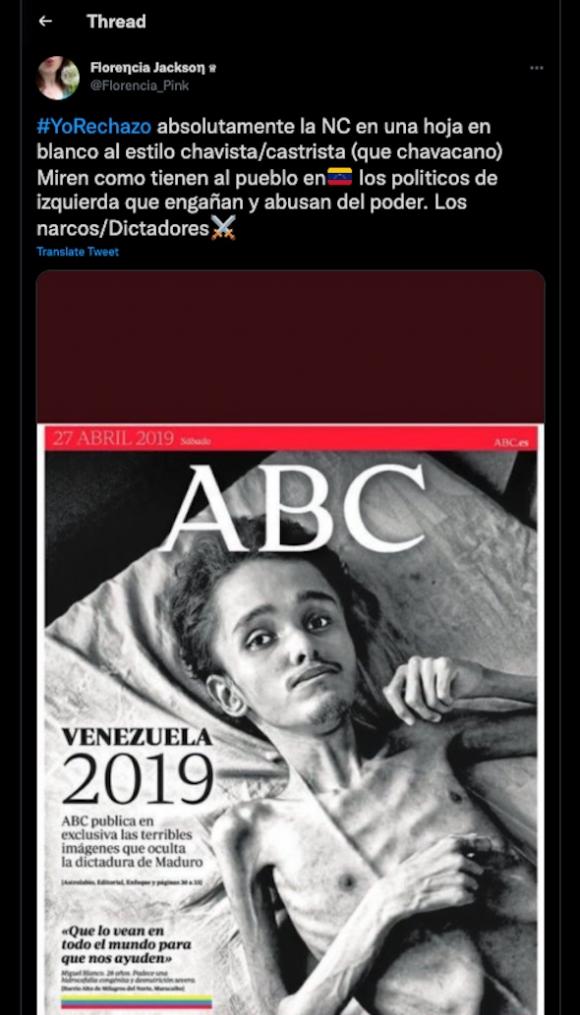

Another example of misinformation spreading through the Rechazo hashtag involved the use of recontextualized media. A prominent example of this originated during the first megatuitazo on Jan 9, 2020, when the influential right-wing Twitter account @Florencia_Pink (32.5K followers) posted a picture from the newspaper ABC of a malnourished Venezuelan child and wrote that she "rejects absolutely” (#YoRechazo absolutamente) the new constitution because it was a “Chavist/Castroist” project.

- 1Sergio I. Melnick (@melnicksergio), “Nueva trampa de la izquierda: El plebiscito tiene sólo dos opciones, rechazo y apruebo. Resulta que el rechazo recibe LA MITAD de financiamiento que el apruebo.. ¿es justo?....obviamente que no. La izquierda hace trampas #RECHAZO” Twitter, September 9 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/P5LA-FGSP.

- 2 Verónica Welkner (@@VeronicaWelkner) “No. Una nueva constitución es sólo para crear una Asamblea Constituyente al estilo chavista y poder coartar las libertades básicas como la libertad, la vida y la propiedad privada, es un engaño de la ultra izquierd,” Twitter, October 29 2019, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/QUU4-GMWJ.

- 3 Pancho de la Cerda (@pancho_cer), “Lo peor es el fin de la propiedad privada y perdida absoluta de la libertad ,pasó en Rusia 1917, en China 1949, Alemania Oriental, Polonia, Checoslovaquia, Rumania, Corea del Norte, Vietnam, Albania, Letonia, Lituania, Ucrania, Cuba 1959, etc,” Twitter, October 20 2019, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/MWE5-Q3UP.

- 4 www.lexjuicios.cl (@lexjuicios) “Una nueva constitución arreglada con trampas ocasionará la pérdida de la propiedad privada, así también las libertades individuales.” Twitter, October 29 2019, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/WY8S-XU3M.

- 5 “Emisión Franja Electoral 25 de septiembre Tarde (segunda Cedula) NOT YET RATED” CNTV, September 24 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/Q8TV-SKBP.

Figure 8: Tweet from account @Florencia_Pink reads: “#YoRechazo (I reject) absolutely the NC (new constitution) a blank page in the Chavist/Castroist style” and refers to leftists that “lie and abuse power.” Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/X2EA-VQTP. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

The tweet connecting constitutional reform in Chile with Venezuela-style poverty was retweeted 389 times, mainly by right-wing accounts, including by the long-time right-wing online figure @Makeka and @CostaPardaa, an anonymous pro-Kast account with 30.9K followers. Florencia_Pink’s image has since reached 201,282 people, according to Twitter data accessed via Brandwatch.

The anti-socialist false claims were spread with the #YoRechazo hashtag along with other misinformation, such as claims that a certain kind of ID was necessary to vote. 1

The #YoRechazo campaign wasn’t the only camp trying to rally voters online through campaign messaging. The Apruebo campaign was actively promoting their choice in the referendum using the Twitter hashtag #YoApruebo and slogans like “Si po, Apruebo” (“Of course, I approve”), but without much coordination. The Apruebo camp did not hold megatuitazos, and its hashtags and slogans did not see online spikes on random days that did not correspond with news regarding the constitutional process.

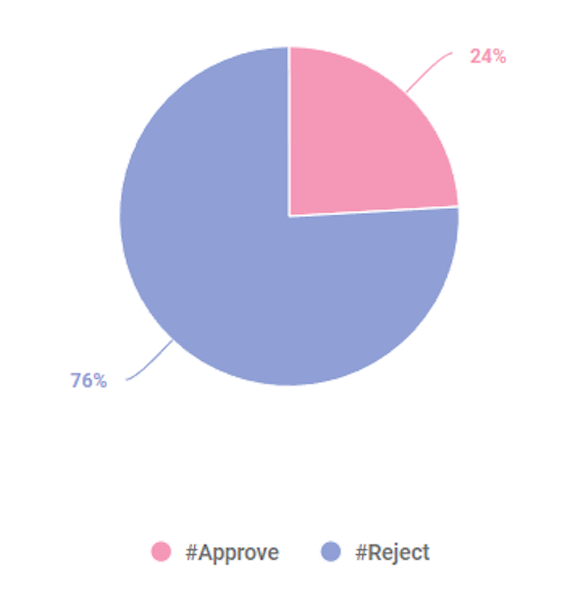

The more coordinated aspects of the Apruebo campaign played out on the streets of cities across Chile, in the mass protests that had not ceased since October 2019. Yet this grassroots movement never gained much traction online compared to Rechazo. Throughout 2019 and 2020, the Rechazo camp’s campaign hashtagging far outpaced the efforts of the #YoApruebo camp. #YoRechazo was often mentioned more than four times as much as #YoApruebo.

- 1 Servicio Electoral (@ServelChile), “¿Aún tienes dudas si podrás votar con tu Cédula de Identidad y Pasaporte vencidos? Recuerda que para este 25 de octubre podrás votar con tus documentos vencidos hasta en 12 meses. #Plebiscito2020 #Servelmáscerca #EligeElPaísQueQuieres” Twitter, September 10 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/E3QR-JYST.

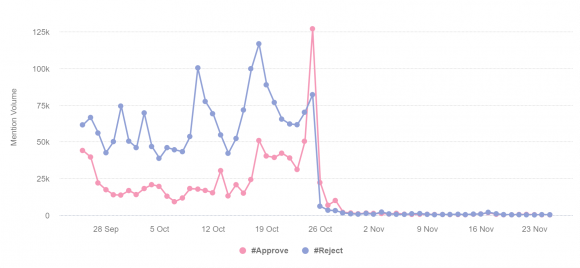

Figure 9. Number of mentions using hashtags related to Rechazo and Apruebo between November 2019 and January 2021. Source: Brandwatch Analytics. Archived on perma.cc, https://perma.cc/G23E-P7PF. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

On two specific days in 2020, the Apruebo hashtag gained more visibility than the Rechazo campaign online. The first was April 26, 2020 – the day the referendum had initially been scheduled, before the pandemic hit. That day, Apruebo mentions spiked from a rolling average of 2,229 tweets daily to a high of 102,837. The second peak for Apruebo was Oct. 25, the day the referendum was actually held, when mentions rose from a rolling average of 41,374 a day to reach a total of 125,543. On the days most critical to the constitutional process, online support for the Apruebo actually appeared to reflect public opinion. At all other times, Rechazo’s online media manipulation campaign drowned out the Apruebo camp online.

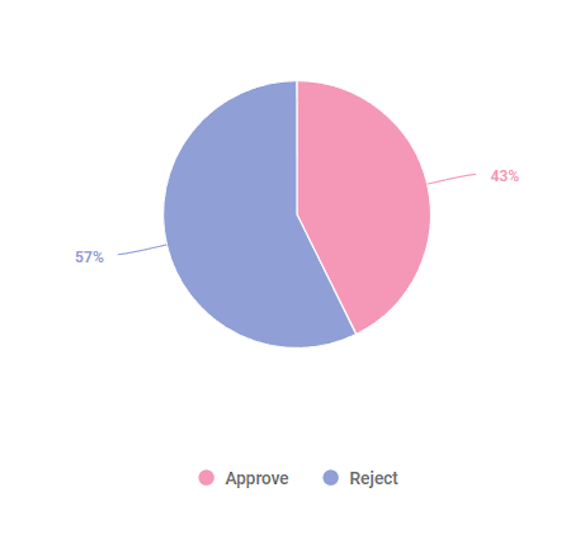

Figure 10. Pie chart showing the use of Apruebo vs Rechazo hashtags between Oct. 18, 2019 and Oct. 25, 2020. Though polls and a majority of politicians and voters in Chile supported the Apruebo vote, Rechazo was significantly more visible online. Source: Brandwatch Analytics. Archived on perma.cc, https://perma.cc/5DZT-9KGG. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

The Rechazo campaign achieved peak exposure on social media on March 7, 2020, the day of a large street protest against the referendum. In part, that peak of online mentions is because a Rechazo protester allegedly attacked a well-known TV reporter;1 images of his bloodied face were circulated online. Violence often acts as a catalyst for media coverage and online conversation.2 But the Rechazo’s online peak that day also seemed to demonstrate a more organic, broad-based show of online support for the cause. There were a total of 129,459 mentions using the “Rechazo” hashtag, made by 26,092 users – not just a small group of super-active users as had previously been the case. Rechazo appeared to be garnering more real world support.

Soon after, Covid ushered in an era of prolonged lockdowns and curfews across Chile.3 The referendum was postponed, and the right-wing campaign against it paused temporarily as Chile’s government prohibited election campaigning (by law, political campaigns in Chile may promote their cause for only two months before an election). The Rechazo hashtag reignited on Aug. 26, 2020, when campaigns were allowed to relaunch.

Around the same time, mainstream polls like Cadem showed the “Apruebo” option was far more popular with the Chilean people, with 75% of those polled saying they were for a constitutional rewrite and 17% against.4 Agenda Criteria, another poll published in September 2020, showed similar results.5

There was one aberration: On Sept. 5, 2020, an Argentinian publicity and marketing firm called Numen published projections favoring the Rechazo camp, with 53% of those polled reporting they were against and 47% saying they were for the Apruebo.6 On the first day, the poll received little play online: just 708 mentions by 474 users on Twitter. Of these 474 accounts, 94 – or 20% – demonstrated what we considered to be "anomalous" characteristics. We defined as “anomalous” accounts that tweeted at extremely high volume; shared identical right-wing identifiers in their bio (“patriota,” “pinochetista” etc); used the same words to characterize the Rechazo’s opposition (“ultraleftists,” “corrupt politicians,” “Chavist,” and “coup,” among others); and which repeatedly tweeted at, retweeted posts from, and were retweeted by the same set of political accounts, namely those of Kast, Melnick, and de la Carrera.

But Numen’s poll soon gained traction. On Sep. 6 the results of this small, foreign-run poll were published (in print) by El Mercurio, Chile’s main newspaper and one of its biggest media conglomerates. El Mercurio is known for its alignment with right-wing parties.7 In the 1980s and ’90s, it supported Pinochet’s dictatorship and according to CIA documents played a role in destabilizing the socialist regime of Salvador Allende, which was overthrown by Pinochet.8

- 1Leonardo Casas, “Desmanes en marcha del Rechazo: golpean a periodista Rafael Cavada” Biobio Chile, March 7 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/H6PT-ZK9W.

- 2 Joan Donovan and Danah Boyd, “Stop the Presses? Moving From to in a Networked Media Ecosystem,” American Behavioral Scientist 65, no. 2 (February 1, 2021): 333–50, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/S97Y-498N.

- 3 Reuters, “Chile announces nationwide nightly curfew, coronavirus cases hit 632”, National Post, March 22 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/XVJ6-5394.

- 4Sebastián Labrín and Sebastián Rivas, “Los votantes del plebiscito bajo la lupa”, La Tercera, September 19 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/9PVA-RWBG.

- 5 “Encuesta Agenda Criteria confirma que la mayoría de los electores de Piñera están por el Apruebo”, El Mastador, September 3 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/93ES-G2C5.

- 6Defensoría Judicial de Carabineros (@EduardoMadari13), “TWITASO AHORA #RECHAZOCRECE Según última Encuesta NUMEN de Argentina. 16.000 personas, la mando a hacer Gonzalo de la Carrera 53% votaría rechazó y un 47% apruebo. Pero como los del Rechazo creen que van a perder, sólo un 22% iría a votar. Si revertimos esto el Rechazo Gana”, Twitter, September 5 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/R38X-2MZD.

- 7Sofía Del Rio, “Encuesta CHILE Septiembre 2020”, September 18 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/TTE5-9JDU.

- 8Francisca Skoknic, “El rol de Agustín Edwards antes y después del 11 de septiembre de 1973”, CIPER, September 10 2013, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/FKV2-HLCL.

Figure 11. El Mercurio, the biggest newspaper in Chile, was the only one that published the dubious results of a poll by an Argentine PR firm finding that the Rechazo side would win the referendum. Source: El Mercurio. Archived on perma.cc, https://perma.cc/ZJ6N-AXL5. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

Between Sep. 5 and Sep. 6 there were 4,429 mentions of the poll on Twitter, notably by Kast, de la Carrera,1 and the right-wing congressman Antonio Coloma, who had 32.4K Twitter followers in mid-December 2021, at the time of writing. In this case, rather than amplify tweets by smaller accounts by retweeting, the politicians directly promoted Numen’s pro-Rechazo poll results to their large audience of followers. Kast tweeted that “polls are starting to show that the Rechazo is growing”2 and Coloma tweeted, “If all of the rechazo vote, we can win.”3

The other polls4 – and Chilean pollsters – suggested this couldn’t possibly be true.5

- 1 Gonzalo de la Carrera DIPUTADO (@carreragonzalo), “Según ultima Encuesta 53% votaría rechazó y un 47% apruebo. Pero como los del Rechazo creen que van a perder, sólo un 22% iría a votar. En cambio un 53% de los del Apruebo irán a votar. Si revertimos esa falsa sensación de que gana el Apruebo , el Rechazo podría imponerse!”, Twitter, September 5 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/77SV-UFC8.

- 2 José Antonio Kast Rist (@joseantoniokast), “Las encuestas empiezan a mostrar que #RechazoCrece y la izquierda se indigna por los que pacíficamente salen a caminar por veredas respetando las normas sanitarias. Por un lado no quieren suspender el Plebiscito, por otro, quieren ponerle un bozal a las personas y censurarlos,” Twitter, September 6 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/3NRB-B4TB.

- 3Coloma Diputado (@Tono_Coloma), “Depende de nosotros !!! Si todos los del #Rechazo vamos a votar el 25 de octubre podemos ganar, PERO si por miedo nos quedamos en la casa, no tenemos opción. El 25 de octubre nos jugamos los próximos 40 años. Tal como paso en el Brexit, tal como paso en Colombia…,” Twitter, September 6 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/4MZW-57VX.

- 4 Sebastián Labrín and Sebastián Rivas, “Los votantes del plebiscito bajo la lupa”, La Tercera, September 19 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/6STG-CVDC.

- 5“Encuesta Agenda Criteria confirma que la mayoría de los electores de Piñera están por el Apruebo”, El Mostrador, September 3 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/U6DU-V7GK.

Stage 3: Response by industry, activists, politicians and journalists

On Sept. 15, 2020, Fernando Cerimedo, CEO of the PR firm Numen Publicidad, was asked about the surprising results of his poll by a reporter on Duna,1 a Chilean local radio station. He said the client who had requested his company conduct the published poll was a group of Chilean entrepreneurs financing the “Rechazo” campaign.2 When pressed by a Duna reporter on the identity of these people, he added that an earlier, unpublished Numen poll conducted for the research purposes of the Rechazo camp had been commissioned by Gonzalo de la Carrera himself;3 de la Carrera later admitted to commissioning “a poll” from a “foreign firm.”4 De la Carrera was working with Numen and paid for at least one poll. It is not established that he paid for the published poll that showed Rechazo winning.

Meanwhile, the “Rechazo” campaign continued to garner a tremendous amount of mainstream media exposure as part of intense, ongoing coverage of the referendum process. According to our analysis of digital media stories published in the week prior to Chile’s referendum, these articles mentioned the word “Apruebo” 11,199 times and “Rechazo” 15,016. A Media Cloud search of all news sources in Chile – which includes print, digital, radio and TV – likewise shows Rechazo coverage dominating in the two-month campaign period before the vote.

- 1Felipe Alcaíno, “Fernando Cerimedo y encuesta sobre Plebiscito: “No es que gana el Rechazo, hay diferencia en la amplitud de los datos,” Duna FM 89.7, September 15 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/79WT-2U5W

- 2Radio Duna (@RadioDuna), “ #NadaPersonal | @FerCerimedo_ARG y encuesta argentina sobre el Plebiscito: "Entiendo que fue un grupo de empresarios de Chile que están aportando a la campaña del Rechazo," Twitter, September 16 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/PN99-QZ2E

- 3Felipe Alcaíno, “Fernando Cerimedo y encuesta sobre Plebiscito: “No es que gana el Rechazo, hay diferencia en la amplitud de los datos,” Twitter, September 15 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/79WT-2U5W

- 4 SALUD NATURAL #Rechazo (@SaludNatural_1), “Patriotas Gonzalo de la Carrera nos dice: La última encuesta del Comando del Rechazo gana por un 53 % El problema es que los medios de comunicación han convencido que perderá el Rechazo y la gente les cree y no quiere ir a votar por miedo al contagio. Vamos a votar! #YoRechazo,” Twitter, September 5 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/3B73-G2JC

Figure 12. Pie chart showing total number of mentions in news sites between 18 Oct. 2019 and 24 Oct. 2020. Source: Brandwatch Analytics. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/B4KN-ZXVR. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

Figure 13. Analysis of a dataset of all stories published in the two months prior to the referendum in Chilean print, radio, digital and TV news outlets shows that Rechazo coverage dominated Apruebo on most days. Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/ZDP6-VTV9. Source: mediacloud.org. Credit: Media Cloud and Highcharts.com.

Rechazo was getting substantially more page time than Apruebo, despite the fact that it was lagging in most polls. The media’s disproportionate focus on the Rechazo campaign did not reflect public opinion in Chile, based on opinion polling at the time.1

Few of these articles in mainstream Chilean outlets like El Mercurio and La Tercera examined the online aspect of the Rechazo campaign, according to our research. Instead journalists did standard election coverage: They wrote about when and where the Rechazo’s official campaign events were held,2 or why voters planned to vote for or against a new constitution.3 Other stories highlighted potential problems with the upcoming referendum, but few talked about misinformation or manipulation online. Instead, these stories discussed whether there would be violence at the polls and if it was safe to vote during a pandemic.4 This indicates that the mentions of Rechazo in the press at this time were largely not skeptical but were rather amplifying the narratives of the Rechazo campaign.

At this time, many Chilean reporters were not covering the power of social media to distort perceptions of reality (with rare exceptions, like this story, from the magazine Pulso, about going after the candidates in the 2017 Chilean presidential race).5 The mainstream media’s “both sides” coverage of the referendum, combined with the Rechazo’s dominance on social media, gave the impression that Rechazo was a significantly more competitive option at referendum than it was.

The Rechazo’s online campaign tactics received virtually no scrutiny before the vote. The only example of about the online campaign was a Sep. 13, 2021, story published by the authors of this case study in the Center for Journalism Research, (or CIPER, a Chilean non-profit investigative news site).6 In it, we documented over a ten-week period a “digital guerrilla campaign” in which the Rechazo had achieved what we called “agenda capture” (copamiento de la agenda) in Chile, showing how an online network had managed to game Twitter’s algorithms to create the impression that many people disliked and opposed Chile’s constitutional convention, despite its positive polling.

A media manipulation campaign of this sort had never been uncovered before in Chile. To write about it we had to create an entirely new vocabulary that would communicate with a Chilean audience. Our efforts had some reach: The Twitter post from CIPER promoting that story reached about 500,000 people, according to our analysis of Twitter data.

On Oct. 25, 2020, the vote finally took place: With 50.9% of the electorate casting ballots – a percentage point higher than Chile’s last presidential election, in 2017 – Chileans voted 78.3% to 21.7% to ditch their Pinochet-era constitution and write a fresh one. The Apruebo win led to the creation of a Constitutional Convention,7 to which 155 delegates representing the diversity of Chile’s population in terms of gender, ideology and ethnicity, were later elected in May 2021.8 They convened for the first time to begin their work drafting a new constitution in June of 2021.9

- 1Sebastián Labrín and Sebastián Rivas, “Los votantes del plebiscito bajo la lupa,” La Tercera, September 19 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/T55P-GN8Q

- 2 “Banderazos, caravanas y juegos online: comandos del Apruebo y Rechazo cierran campañas en el último día de legal,” La Tercera, October 22 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/7JBB-F56L.

- 3 Sebastián Labrín and Sebastián Rivas, “Los votantes del plebiscito bajo la lupa,” La Tercera, September 19 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/T55P-GN8Q.

- 4 Valentina Durán, “Plebiscito en pandemia: las estrategias y dificultades de una campaña atípica,” La Tercera, October 24 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/8WUQ-RQ9G.

- 5 PULSO, “La desatada guerra presidencial de los " ", "trolls" y "fakes," La Tercera, October 16 2017, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/2UZB-H64M

- 6 Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence, “Guerrilla digital contra la Convención Constituyente,” CIPER Chile (blog), September 13, 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/2DZM-W4RN.

- 7Jennifer M. Piscopo and Peter Siavelis, “Chile Abolishes Its Dictatorship-Era Constitution in Groundbreaking Vote for a More Inclusive Democracy,” The Conversation, October 26, 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/3MZH-Z7TA.

- 8Marcela Ríos Tobar, “Chile’s Constitutional Convention: A Triumph of Inclusion,” UNDP, June 3, 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/W8YS-3APQ.

- 9 “Proceso Constituyente,” Gobierno de Chile (Gob.cl), accessed December 16, 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/W92Q-EWMP.

Stage 4:

The barrage of misinformation failed to win the election for Rechazo, but it succeeded in muddying the waters before the referendum in Chile, creating a confusing and disorienting electoral environment in the months before the vote. It became so difficult for Chileans to tell what was real and what was false regarding the upcoming referendum that the Chilean Electoral Service on Aug. 10, 2020, launched a service to combat misinformation1 on its Twitter account2 and on its webpage. The agency had never done this for any other vote. The decision was made just before the election campaigns were to relaunch post-pandemic lockdown.

According to the Chilean Electoral Service’s director Patricio Santamaría, in the newspaper El Mostrador, the unprecedented step was necessary because social media was making “fake news fly faster and reach many more people.” He said democracy “can’t be stopped” by the “fake news that is affecting the electoral system worldwide.”3

Critical press of the Rechazo campaign’s online tactics began just weeks before the vote.

On Oct. 13, 2021, in El Mostrador, the journalist Felipe Saleh published an article alleging that the Rechazo campaign was using a “digital army” of bots “not to win the election but to interfere and steer the political discussion.”4 The article included interviews with political scientists and academics who gave their views of the Rechazo’s online campaign. In it, one sociologist referred to Kast as “an expert of the old school bot-based digital campaign,” essentially accusing him of running the #YoRechazo media manipulation campaign and of using inauthentic accounts as part of it.

It was not the first time Kast had been accused of using bots. In April 2019, Kast – a two time presidential candidate – was accused of using bots to manipulate an early Twitter poll for the 2021 presidential election.5 The political scientists in charge of the poll concluded that they had “funded suspicions of irregular activity” and eliminated Kast from the online voting.

On Oct. 17, the authors of this case published another investigation in CIPER based on the social media monitoring we had conducted over the past year of Chile’s constituent process.6 In it, we documented that the vast majority of the Rechazo camp’s online messaging had been promoted by accounts meeting our definition of "anomalous."

The 999 accounts that met these criteria posted a total of 391,000 messages using the hashtags of the Rechazo campaign between Oct. 18, 2019 and Oct. 13, 2020. That meant that “2% of authors generate more than 10% of Rechazo mentions,” we wrote. These were behind every spike in the Rechazo campaign’s online presence, every time #YoRechazo became a Twitter trending topic. We cannot determine with certainty whether they were bots or authentic accounts – a distinction that is notoriously difficult to make, especially given that most tools used to identify bots work best in English.

Starting in October 2019 and early 2020, a few Chilean and newly created fact-checking organizations worked to fact-check and debunk demonstrably false claims frequently being spread along with the #YoRechazo hashtag – such as the claim that a new constitution would abolish private property or turn Chile into Venezuela, and misinformation about voting requirements in the referendum. In April 2020, three non-profit organizations – the women’s rights group Corporación Humanas, the pro-democracy think tank Fundación Espacio Público, and the human rights NGO Observatorio Ciudadano – teamed up with Chile’s Universidad Diego Portales to create Contexto, a website that debunked, among other misinformation, the Rechazo TV ad claiming that a new constitution would endanger the right of private property, among other efforts.7

Fast Check, a Chilean fact-checking website created in 2019, also marked the same ad with a label of “FAKE” on Oct. 8 2020.8 The Fast Check post quoted a Chilean constitutional lawyer, Rodrigo Pérez Lisicic, calling that idea “a fallacy.”

Decodificador Chile – a relatively new platform born in April 2020 – debunked the fake Rechazo-affiliated claim about Chileans losing their right of private property,9 among other rumors.10

Chilean fact-checkers struggled to effectively mitigate the spread by the campaign, like the image of the starving child accompanied by text claiming that a new constitution would plunge Chile into Venezuela-like poverty and crisis like Venezuela.

Though Twitter and Facebook routinely remove some fraudulent accounts in Chile, the companies claim they do not have the capacity to remove every single one of these accounts.11 Very few of the anomalous accounts that helped spread fake news around Chile’s referendum were removed: 169 of the 999 accounts we considered anomalous during the #YoRechazo campaign were either suspended or no longer exist. We can find no apparent logic to why these 169 accounts went offline while others remain active.

Two days after the 2020 referendum, the publicity firm Numen publicly reassessed its findings in favor of Rechazo. On Oct. 27, a small media outlet called Diario La Segunda reported in a short column that Numen’s CEO Cerimedo, in a thread posted to his Twitter account, had attributed the surprising results of the poll to an error in calculation.12

In his posts, Cerimedo wrote that “our error of analysis and calculation was because we didn’t take into account the variables of the plebiscite and we used formulas of cases where voting is mandatory.” In Chile, voting is optional; in Argentina, where Numen is based, voting is required. Aside from the column in La Segunda, this correction was only picked up by the website 24horas.13

- 1 “El combate del Servel contra la desinformación y las noticias falsas,” Servicio Electoral de Chile, October 23 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/TP2Y-APB9.

- 2 Servicio Electoral (@ServelChile), “Para el #Plebiscito2020 asegúrate de informarte por las redes sociales oficiales del #Servel y http://servel.cl y http://plebiscitonacional2020.cl Que no te desinformen. #Servelmáscerca #EligeElPaísQueQuieres,” Twitter, March 9 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/Z5J3-LCVA.

- 3 José Olavarría, “Con mascarilla, lápiz azul y sin miedo: el manual anti fake news para votar en el plebiscito del 25-O” El Mostrador, October 23 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/Z5J3-LCVA.

- 4Felipe Saleh, “El "ejército digital" del Rechazo y la estratégica apuesta por la gran batalla en redes para abril,” El Mostrador, October 13 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/YTZ8-WAFW.

- 5Andrés Muñoz, “Acusado de "meter bots": J. A. Kast es eliminado de encuesta presidencial de Twitter,” La Tercera, April 18 2019, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/DN5X-6WJN.

- 6Patricio Durán, Tomás Lawrence and Juan Esteban Fernández, “La red social Twitter y el proceso constituyente: el caso de las cuentas anómalas,” Ciper, October 17 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/E3BN-LDHF.

- 7Valentina Matus Barahona, “Franja del Rechazo señala que una nueva Constitución pone en peligro el derecho de propiedad,” Contexto, 13 Oct 2020, archived on https://perma.cc/Q3MJ-PM64

- 8Elías Miranda, “‘Si la Constitución es concebida bajo la igualdad colectiva, pones en peligro tu derecho de propiedad’: #Fake,” Fast Check CL (blog), October 8, 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/GA5S-GSJT.

- 9Camila Silva PyL, “La convención constitucional pone en riesgo el derecho de propiedad,” Decodificador Chile, September 28 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/V6JD-L9FM.

- 10Camila Silva PyL, “Marcela Cubillos: “Diputados constitucionales le costarán a todos los chilenos $9.500.000 mensuales,” Decodificador Chile, September 23 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/QZ4Y-PPL3.

- 11Cat Zakrzewski, Gerrit De Vynck, Niha Masih and Shibani Mahtani, “How Facebook neglected the rest of the world, fueling hate speech and violence in India,” The Washington Post, October 24 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/3PLQ-J2VV.

- 12Juan Pardo Escámez (@Chilesoc), “#Plebiscito2020 #25Octubre #Chile #Encuesta En el capítulo de "excusas inaceptables" hoy en @La_Segunda NUMEN se enteró "por la prensa" que el voto era voluntario... se ve que era un trabajo muy profesional... Un poquito de pudor…,” Twitter, October 27 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/U6QQ-RLVQ.

- 13“Empresa Numen tras proyectar un 41,9% para el "Apruebo": "Analizamos y proyectamos los datos con voto obligatorio," October 28 2020, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/SRD5-JMEM.

Stage 5: Adjustments by manipulators to new environment

The day after the referendum, social media mentions of Rechazo dramatically fell off. Most of the misinformation about the constituent assembly that had accompanied the #YoRechazo hashtag also stopped spreading after Oct. 25, 2020.

Figure 14. Number of mentions using hashtags related to Rechazo and Apruebo one month prior and one month after the Oct. 25 plebiscite. Source: Brandwatch Analytics. Archived on perma.cc, https://perma.cc/4YVP-3SWJ. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

For example, we found no evidence that the Rechazo campaign operators relaunched their efforts during the May 2021 election of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention.

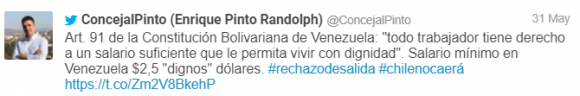

However, this was not the end of the Rechazo campaign. On July 4, 2021 – the day that the newly elected Constitutional Convention first met – the campaign relaunched using a similar strategy as before: , promoted by the same core group of hyper partisan pro-Republican accounts, such as @Francis25830 or @FridaSikahlo. 1299 accounts of the 3929 that spread the hashtag #RechazodeSalida on Jul. 04, also had previously posted the #YoRechazo on Jan. 09. The campaign adapted to the new political situation by adopting a new hashtag: #RechazodeSalida (#RejectintheExit). This was a reference to yet another referendum that will be held in Chile once the new Constitution is written, in which Chileans will vote whether to adopt the new document or not.

Figure 15: A tweet by @ConcejalPinto reads (translated into English): “Art. 91 of the Bolivarian Constitution of Venezuela: “every worker has the right to a salary sufficient to let him live with dignity.Minimum wage in Venezuela is $2.5 “dignified” dollars. #rechazodesalida #chilenocaerá." Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/Q8AL-LTL4. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

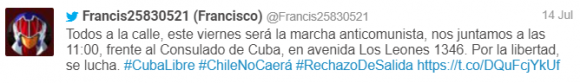

FIgure 16: A tweet by @Francis25830521, a major anonymous account in the #YoRechazo campaign, read (translated into English): “Everyone to the streets, this Friday will be the anti-communist march, we’ll get together at 11:00 in front of the Cuban Consulate, at 1346 Ave. Los Leones. For liberty, we fight.#CubaLibre #ChileNoCaerá #RechazoDeSalida.” Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/2NN6-8UUR. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

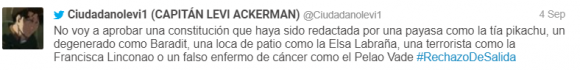

Figure 17. A tweet by @carreragonzalo reads “Que ingenuidad la de gran parte de Chilevamos al despejarles la pista para que la izquierda desmantele la institucionalidad. A quién le favorece acabar con @Carabdechile ? Solo a los anarco delincuentes. #RechazoDeSalida,”Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/227R-MVJ3. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

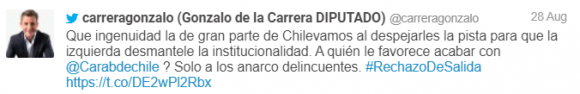

Figure 18: A tweet by @Ciudadanolevi1 reads: “No voy a aprobar una constitución que haya sido redactada por una payasa como la tía pikachu, un degenerado como Baradit, una loca de patio como la Elsa Labraña, una terrorista como la Francisca Linconao o un falso enfermo de cáncer como el Pelao Vade #RechazoDeSalida” Archived on Perma.cc, perma.cc/PET9-DJZ9. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

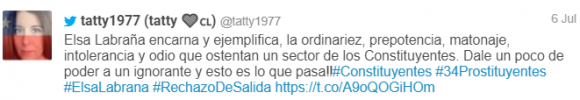

Figure 19: A tweet by @tatty1977 reads “Elsa Labraña encarna y ejemplifica, la ordinariez, prepotencia, matonaje, intolerancia y odio que ostentan un sector de los Constituyentes. Dale un poco de poder a un ignorante y esto es lo que pasa #Constituyentes #34Prostituyentes #ElsaLabrana #RechazoDeSalida,” Archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/MU4A-B9LF. Credit: Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence.

With this tactical redeployment, the coordinated campaign entered its third year in Chile, with a new target: the constitutional convention itself. Its left-wing members, particularly the Indigenous president of the convention, Elisa Loncón,1 have been the subject of intense , misinformation2 and death threats3 on Twitter, as documented by the online outlet Contexto.4 We found 580 out of the 1,842 accounts that published the hashtag #DestituciónadeElisaLoncón (“Fire Elisa Loncón”) in 2021 had also engaged in the #YoRechazo mega tweetathon on Jan. 8-9, 2020.

And though Rechazo lost the election, the same right-wing narrative promoted by #YoRechazo about the perils of change in Chile persists in national conversations about democracy. It also dramatically bolstered the public profile of José Antonio Kast.

The most successful false narratives spread to undermine the constitutional process have become central to Kast’s 2021 presidential campaign. These include the Chile-Venezuela scare tactic; Kast frequently mentions that Cuba and Venezuela are allies of his leftist opponent, Gabriel Boric.5 He also capitalized on the property rights misinformation, which he helped turn into an unexpected in Chile’s 2021 election by repeatedly defending Chileans’ supposedly threatened right to private property.6 We say unexpected because there is no chance, nor was there ever any indication, that Chile’s new constitution, if adopted, would abolish private property.

On Dec .19, 2021, Kast lost to the 35-year-old leftist Gabriel Boric in the runoff of Chile's two-round presidential election, which saw unusually high turnout. Kast received 44 percent of the vote to Boric's 56 percent.

- 1Eva Ontiveros, “Elisa Loncón: From poverty to PhD to writing Chile's constitution,” BBC World Service, July 11 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/G7KF-82BV.

- 2“Piñera confirms police protection for Elisa ‘Loncón’ after threat report and becomes TT | Special,” Newsbeezer, July 18 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/7W6B-3TG5.

- 3Ibid.

- 4Valentina Matus BarahonaPatricio Durán, “Las cuentas detrás del hashtag que pide la destitución de Elisa Loncón,” Contexto, July 29 2021, archived on Perma.cc, perma.cc/3CYB-33NA.

- 5José Antonio Kast Rist (@joseantoniokast), “La @OEA_oficial condena con fuerza las elecciones ilegítimas del Dictador Ortega en Nicaragua. No hay elecciones democráticas cuando los candidatos opositores están en la cárcel. Es el mismo manual de Cuba y Venezuela, los aliados del Partido Comunista y Gabriel Boric,” Twitter, November 13 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/CT2X-ESHC.

- 6José Antonio Kast Rist, “Atrévete Chile,” 2021, archived on Perma.cc, https://perma.cc/8KZ4-9FEG

Conclusion

This case demonstrates that an official campaign hashtag used to promote a ballot choice can verge into media manipulation territory when it involves a call to game the algorithm, highlighting the blurry line between legitimate digital political campaigning and questionable online practices. It also points to the often invisible way online conversations can influence media coverage–and the importance of journalists being trained to monitor for and identify irregular online activity surrounding key events like elections. The coronavirus pandemic is also a salient factor in this case. The length of time between the announcement of Chile's referendum and the actual vote created opportunity for people to reach voters in many ways; using Twitter and an electoral process open to political campaigning, some used that opportunity to influence the vote through media manipulation.

This case has been updated to reflect the final results of Chile's 2021 presidential election and to correct Gabriel Boric's age.

Cite this case study

Patricio Durán and Tomás Lawrence, "Constitutional Vote In Chile Targeted By Coordinated Hashtag Campaign Before Election," The Media Manipulation Case Book, February 1, 2022, https://casebook-static.pages.dev/case-studies/constitutional-vote-chile-targeted-coordinated-hashtag-campaign-election.