Dueling Information Campaigns: The War Over the Narrative in Tigray

Overview

This case study focuses on competing information campaigns related to the active military conflict in the Tigray region of Ethiopia, which began in November, 2020. Amid the information and access constraints during the ongoing crisis, contesting narratives designed to influence international understanding of the conflict played out largely on . Employing a mixed methods approach, this case study details the strategies and tactics of two key online communities participating in these outward-facing advocacy campaigns: the Ethiopian government and its supporters, and Tigrayan organizers and their allies in the diaspora and in Ethiopia.

Background

Tensions between the Tigray region and Ethiopia’s federal government increased significantly when Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed dissolved the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), to form his Prosperity Party in 2019. The EPRDF coalition ruled Ethiopia for nearly 30 years, and was made up of four political parties representing regional ethnic groups. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) controlled many of the most powerful positions in this coalition. Abiy Ahmed was a long-serving member of the EPRDF, but came to power on a wave of popular protests and was initially celebrated as a reformist Prime Minister. His peace deal with Eritrea won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019. Since coming to office he has pursued a political agenda that challenges Ethiopia’s system of “ethnic federalism.” Tigrayans and some other minority ethnic groups worry that this “unitarist” vision will result in their marginalization.

On November 4, 2020, forces loyal to the TPLF attacked Ethiopian National Defence Forces (ENDF) in Tigray. TPLF leadership called the attack preemptive, saying they acted because of information suggesting the ENDF was preparing to attack them, a claim the ENDF denies.1 The central Ethiopian government launched a military response to the TPLF’s attack that day and declared a state of emergency in Tigray.2

The same day, November 4, the federal government shut down the internet and telecommunications across the region, creating an information vacuum.3 Journalists, aid groups, and researchers have struggled to access the region since.4 Telecommunications were restored at certain points during the conflict, but not consistently. The federal government declared a ceasefire and withdrew from Mekelle, Tigray’s capital, on June 28, 2021.5 At the time of writing in August, 2021, communications had not been restored to the region.6

Amid the information and access constraints, competing information campaigns emerged to frame the conflict for English-language Twitter. On one side, Tigrayans and their allies used Twitter to engage in online activism and to share information about events taking place in the region. In reaction to this movement, the Ethiopian government and its supporters launched counter information campaigns to discredit Tigrayan activists, framing the violence as fabricated, exaggerated, or caused by the TPLF. Both media campaigns are directed toward the international community.

This case study tracks the rise and evolution of both information campaigns. It is a complex case that interacts with the geopolitics of the Horn of Africa, historical trauma, activism, hate speech, misinformation, manipulation, and , all in the midst of an ongoing civil conflict.

It is important to bear in mind that the politics of information has a burdened history in Ethiopia. For most of its rule, the EPRDF censored free press and built a robust censorship and surveillance infrastructure designed to quell political dissent.7 Some Ethiopian and social media commentators that appeared independent during the EPRDF years were reportedly paid by the TPLF to spread pro-government messages online.8 At the same time, many media platforms that described themselves as independent had strong ties to opposition groups, reportedly pursuing political agendas under the auspices of journalism.9 Research suggests that the limited press freedom that characterized Ethiopia’s recent history has inflicted lasting damage on Ethiopia’s media landscape.10

Our analysis suggests that fear of poses an additional challenge in this context. “Fake news” functions as a kind of political bogeyman, allowing people to dismiss substantiated reports of atrocity crimes against Tigrayans as fabricated or overblown. The belief in an omnipotent TPLF disinformation campaign may also be politically useful for groups looking to consolidate new forms of power in Ethiopia. Research indicates disinformation accusations may make it easier to ban or discredit genuine online activism.11 By highlighting these dangers, we do not suggest that mis- and disinformation plays no role in this conflict — both campaigns have shared misleading, unverified, and false information, to varying degrees and effects. However, making careful distinctions among actors and the types of information being spread around this conflict may be one means of combating the kind of binary thinking that appears to be fueling polarization around this conflict.

Critically, all our interviewees described a year shaped by anxiety and fear for the future for their country, communities, and loved ones. Tigrayans are living in fear of collective punishment for crimes and corruption during the EPRDF years, and described feeling “gaslight” or “scapegoated” when other Ethiopians dismiss as propaganda credible reports of atrocity crimes against their families and communities.12 Ethiopians currently supporting the government told us that they fear that the TPLF is exaggerating claims of violence in Tigray to provoke international intervention, which they believe would foreclose the possibility of the democratic transition so many struggled for.13 Still others we spoke to feared communal violence across the country, which they believe deserves more media attention.14

To trace the online campaigns that have emerged around the Tigray conflict, we used mixed methods: data collection, interviews with campaign participants and organizers, and open source and secondary research. We describe these methods in detail in Appendix I. For more context about Ethiopia’s history, please see Appendix II, which will aid in interpreting these events, especially in understanding the different political positions around the wedge issue of ethnic federalism versus centralized political power.

- 1 See Appendix 1 for a detailed breakdown of reports of troop movement and political escalation during the days leading up to the conflict. See also: Declan Walsh, “‘I Didn’t Expect to Make it Back Alive’: An Interview With Tigray’s Leaders,” New York Times, July 3, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/03/world/africa/tigray-leader-interview-ethiopia.html.

- 2 Office of the Prime Minister-Ethiopia, “Federal Council of Ministers declares State of Emergency in Tigray Region,” , November 4, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/PMOEthiopia/posts/978946109263239.

- 3 Access Now (@accessnow), “BREAKING: The Government of Ethiopia Has Again Shut down the Internet. Mobile Network, Fixed-Line Internet & Landline Telephony Have Been Cut in Tigray, as PM @AbiyAhmedAli Declares a State of Emergency & Orders Military Intervention against Tigray People’s Liberation Front,” Twitter, November 4, 2020, https://twitter.com/accessnow/status/1323964706382643200.

- 4Simon Allison, “Blackout Makes It Hard to Report on Ethiopia’s Civil War,” Mail & Guardian, November 16, 2020, https://mg.co.za/africa/2020-11-16-blackout-makes-it-hard-to-report-on-ethiopias-civil-war/; “UNHCR Regional Update #4: Ethiopia Situation (Tigray Region), 25-27 November 2020 - Ethiopia,” ReliefWeb, November 28, 2020, https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/unhcr-regional-update-4-ethiopia-situation-tigray-region-25-27-november-2020; Simon Allison, “Blackout Makes It Hard to Report on Ethiopia’s Civil War;” “Demand Full Humanitarian Access into Tigray,” Amnesty International, 2021, ; Michael Oduor, “Ethio Telecom Restores Services to Parts of Tigray,” Africanews, December 2, 2020, https://www.africanews.com/2020/12/02/ethio-telecom-restores-services-to-parts-of-tigray-official/.

- 5Cara Anna, “Ethiopia Declares Immediate, Unilateral Ceasefire in Tigray,” Associated Press, June 28, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/ethiopia-tigray-cease-fire-2745f0941cafcfa8fbe4c9f945f0925d.

- 6Getachew Reda (@reda_getachew), “Statement of #theGovernmentofTigray on conditions for Negotiated #Ceasefire,” Twitter, July 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/reda_getachew/status/1411621680280113156?s=20; Declan Walsh, “Back from three weeks in Ethiopia, mostly in Tigray, where there was a communications blackout which meant I couldn't post updates from the ground. Story in today's paper, but here are some images and thoughts on what I saw,” Twitter, July 12, 2021, https://twitter.com/declanwalsh/status/1414611238047391746?s=20.

- 7Kimiko de Freytas-Tamura, “‘We are Everywhere’: How Ethiopia Became a Land of Prying Eyes,” New York Times, November 5, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/05/world/africa/ethiopia-government-surveillance.html.

- 8Endalkachew Chala, “Leaked Documents Show That Ethiopia’s Ruling Elites Are Hiring Social Media (And Watching Porn),” Global Voices, January 20, 2018, https://globalvoices.org/2018/01/20/leaked-documents-show-that-ethiopias-ruling-elites-are-hiring-social-media-trolls-and-watching-porn/.

- 9Justin Lynch, “The Tragedy of Ethiopia’s Internet,” Vice News, February 1, 2016, https://www.vice.com/en/article/d7ypxx/the-tragedy-of-ethiopias-internet.

- 10Abraham Tesfalul Zere, “Social Media in Exile: Disruptors and Challengers from Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Sudan” (Ohio University, 2020), https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_olink/r/1501/10?clear=10&p10_accession_num=ohiou160397346197175.

- 11Arthur Larok, “Modified Activism After Ethiopia’s New Dawn,” Carnegie Europe, October 24, 2019, https://carnegieeurope.eu/2019/10/24/modified-activism-after-ethiopia-s-new-dawn-pub-80148.

- 12Interview by authors.

- 13lnterview by authors.

- 14Interview by authors.

Stage 1: Campaign planning

Tigrayan diaspora campaign:

When the conflict began on November 4, the internet watchdog organization Netblocks reported an internet network disruption in the Tigray region from 1am local time.1 Immediately after, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed announced on Facebook and Twitter that a “red line” had been crossed and that a "law enforcement” operation was underway to apprehend TPLF leadership.2 English-speaking Tigrayans in the diaspora encouraged supporters to take to Twitter, circulating instructions and videos on WhatsApp describing how to use the platform to raise awareness about the conflict. Thousands of Tigrayans in Ethiopia and the diaspora joined Twitter in the following days, according to an analysis of 90,000 tweets.3 Interviewees also confirmed that many had joined Twitter for the first time in order to participate in online activism.4

One of the most successful examples of activist mobilization in terms of volume of participants is the group Stand With Tigray, founded in the US. “On November 4th, when we heard about the war, we froze,” Lwam Gidey, a US-based undergraduate student originally from Tigray, and the co-founder of Stand With Tigray, told the authors in a phone interview.5 After the Prime Minister’s announcement, Gidey tried to contact her family in Tigray. “We found that there is no telecommunications and we couldn’t reach them,” she said.6 “It was really scary.”

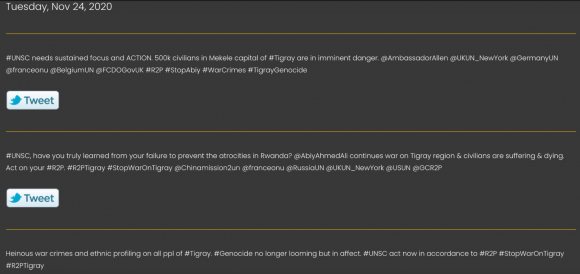

The next day Gidey and her sister began to build a website to raise awareness about the conflict. They launched it November 6, and organized “copy-and-paste” Twitter campaigns via the website. (See figure 1 below).

- 1“Internet Disrupted in Ethiopia as Conflict Breaks out in Tigray Region,” NetBlocks, November 4, 2020, https://netblocks.org/reports/internet-disrupted-in-ethiopia-as-conflict-breaks-out-in-tigray-region-eBOQYV8Z.

- 2“‘The Last Red Line’: Ethiopia Nears Civil War as PM Orders Military into Restive Tigray Region,” France 24, November 4, 2021, https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20201104-the-last-red-line-ethiopia-nears-civil-war-as-pm-orders-military-into-restive-tigray-region.

- 3Claire Wilmot, “What’s Happening in Ethiopia?”, Washington Post, November 17, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/11/17/ethiopias-cracking-down-tigray-activists-are-spreading-news/.

- 4Interview by authors.

- 5lnterview by authors.

- 6Interview by author.

Figure 1: An example of a copypasta Twitter campaign hosted on the Stand With Tigray website in November 2020. Source: https://web.archive.org/web/20201113065541/https://www.standwithtigray….

“We don’t know anyone political, we don’t have connections. We’re just students,” Gidey said. “So I did some research about how best to build a website, and on November 6 we decided that we would call it ‘Stand With Tigray.’ We wanted to call on everyone who was concerned about what was happening to come and stand with us, to end the war and to open up access to Tigray.”1

By the following week, new accounts tweeting in support of Tigray—many using Stand With Tigray hashtags—were responsible for about a quarter of all tweets in English about the conflict.2

As of August 2021, Stand With Tigray has about 20 regular volunteers who organize campaigns and streamline messaging, according to Gidey. Dozens of others are semi-regular, contributing on an as-needed basis. “As more and more people found out about our platform, they would email us wanting to get involved. So now we have more people helping write tweets, people who focus on infographics, and some people who help write and edit tweets and letters,” said Gidey.3 Stand With Tigray does not pay their regular or occasional volunteers, as they are currently self funded. They applied for non-profit status in the US in July, 2021.4

The government and its supporters often describe Tigrayan campaign participants as “pro-TPLF” or members of the TPLF. This is a complicated but important distinction. According to interviews and data analysis, participants in Tigrayan Twitter campaigns may be best understood along a continuum—on one side are Tigrayans and allies who do not identify with any , like Stand With Tigray, but are engaging in anti-war and humanitarian activism. Further along the continuum are activists who support the TPLF politically (or the Tigray Defence Forces (TDF) tactically).5 This category has grown after months of fighting. At the far end of the continuum are public members of the TPLF, though they account for a smaller proportion of users.6 Many participants told us that participating in online campaigns was one way of feeling like they were “doing something” to support their families in Tigray.7

This case study focuses primarily on Stand With Tigray and Omna Tigray because our analysis showed that they play key roles in Tigray Twitter campaign networks. Stand With Tigray operators told us that they have tried to keep their advocacy apolitical.8 But the conflict is political in nature, and operators and participants of some advocacy groups appear to have taken a more overtly political stance as the conflict has progressed.

A major that divides the two campaigns is the degree of political power that should be concentrated in regional governments vis-a-vis the federal government. Many participants in Tigrayan campaigns see Ethiopia’s version of “ethnic federalism” as a means of preserving “unity” in Ethiopia rather than as a tool for secession, as its critics charge.9 They, like activists from some other ethnic groups, such as the Oromo, worry that without a political arrangement that gives significant power to regional governments, majoritarian politics will leave no space for them to express their cultural identities or pursue regional political interests.10 Government supporters often blame ethnic federalism for entrenching divisions among Ethiopia’s many different ethno-linguistic groups.11

Pro-government campaign:

In response to pro-Tigrayan campaigns, Ethiopian state actors and networks of non-government supporters launched their own campaigns to influence international audiences. The most active participants in these networks promote a concept of Ethiopian “unity” that Abiy has pursued since forming the Prosperity Party.12 A major, sustained hashtag campaign in pro-government circles is #UnityForEthiopia.

Major online players in this category include Ethiopian government officials, a coalition of diaspora advocacy groups, individuals and organizations who feel the war is just or necessary, and individuals with ties to the Eritrean government, according to our network analysis and interviews. These participants can also be understood along a continuum of political affiliation and involvement.

We do not have insight into the planning phase of the pro-government response to the pro-Tigray campaign. However, by December, Tigrayan activists had significantly expanded the frequency and volume of their campaigns, which prompted government supporters to organize in response. According to our analysis, about a quarter of accounts that started organizing to combat Tigrayan narratives in December had joined Twitter in July 2020. This uptick in pro-government online activity coincided with a series of protests that emerged in the aftermath of the murder of musician and political activist Hachulu Hundessa, who played a crucial role in inspiring youth protests across the Oromia region in the leadup to Abiy’s appointment as Prime Minister.13 Other government supporters used older social media accounts that had been dormant for some time but began to re-engage in political discourse in July of 2020. With the onset of the conflict in November, these accounts turned their focus to what was going on in Tigray.

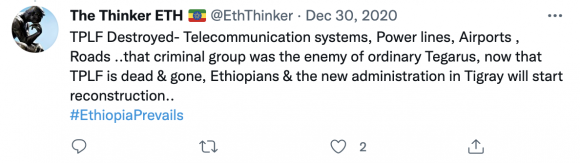

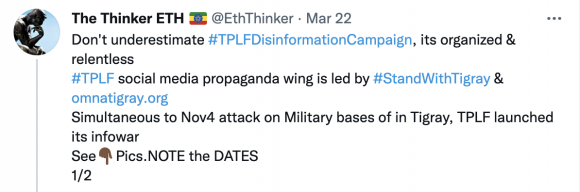

Other participants in this campaign joined Twitter independent of any organized campaign to combat what they described as TPLF disinformation. One early participant said that they joined Twitter in November to counter TPLF “fake news,” and that they believed tweets from Tigrayan activists were part of the TPLF’s strategy to derail Abiy’s political transition and restore themselves to power.14 Participants in pro-government campaigns have different political leanings and degrees of political involvement, but they share a common foe—the TPLF.

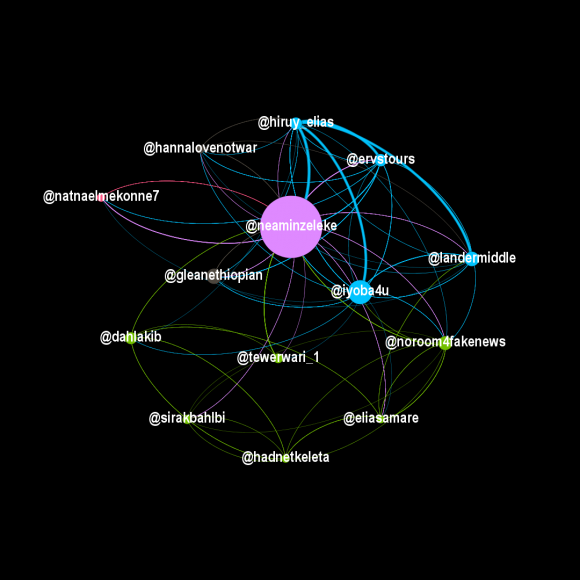

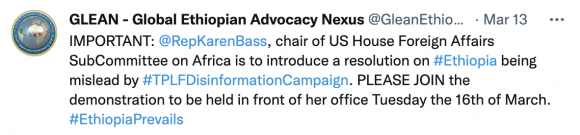

On December 15, groups and individuals who felt Abiy’s actions in Tigray were justified or were being misrepresented organized a meeting on the situation for American policymakers and members of prominent think tanks, according to one of the organizers of the meeting.15 During the meeting, they discussed the need to counter what they saw as the TPLF’s manipulation of the conflict narrative in international discourse, and decided to form an advocacy coalition of their own, known as the Global Ethiopia Advocacy Nexus (GLEAN).16 Glean has become one of the largest organizing platforms for those currently supporting the government, according to our network analysis.17 Key operators of GLEAN maintained that their organization is not aligned with any political party, despite historic ties between operators and Ethiopian political groups. They said they see Abiy as a bulwark against the TPLF and currently support him for that reason. They told us this support is not ideological, but contingent on his actions.18

GLEAN is led by Neamin Zeleke, a long-time member of the Ethiopian opposition during the EPRDF. GLEAN is a coalition made up of four main organizations. The first three are the Ethiopian and American Development Council based in Colorado, Advocates for Ethiopia based in Los Angeles, and an organization called Voters Voice, which consists of younger activists across the US, according to Zeleke.19 “GLEAN is a platform of civic organizations established to mobilize Ethiopians who were not part of our political movement,” said Zeleke.20

The fourth and perhaps the most central is the Ethiopian Advocacy Network, which was established as a communications group by members of an armed political opposition group known as Ginbot Sabat (G7), founded in 2008.21 G7 was made up of members from a political party that made unprecedented gains against the EPRDF during Ethiopia’s violently disputed 2005 elections.22 The aftermath of those elections saw severe government crackdowns on opposition figures. State security forces killed nearly 200 protesters and arrested an estimated 30,000 opposition supporters.23

“As far as some opposition groups were concerned, 2005 was the moment when the prospects of peacefully competing with the EPRDF and the TPLF disappeared,” said William Davison, Senior Ethiopia Analyst at the International Crisis Group in a phone interview. “After that, Ginbot 7 was created, and some members of the Ethiopian opposition started their alliances with President Isaias Afwerki of Eritrea. It’s the bitterness caused by that history, but particularly the experience of 2005, that is partly driving some of the events we’re seeing today.”

Zeleke served as the head of G7’s Foreign Affairs wing until 2018.24 From 2015 and 2018, he spent about half his time in Eritrea, where he says he trained insurgents for Ginbot 7 in politics and leadership.25 After Abiy came to power Ginbot 7 suspended operations.26 Some of G7’s former leaders went on to form the Ethiopian Citizens for Social Justice party, also known as EZEMA.27

Zeleke also helped found and expand Ethiopian Satellite Television and Radio (ESAT), a diaspora-based channel that broadcasts in Amharic and English and is opposed to the EPRDF.28 During Zeleke’s time at ESAT, reports indicate he was the subject of surveillance by the Information Network Security Agency (INSA)—a state intelligence agency that Abiy helped to establish in the EPRDF.29 Individuals associated with ESAT play significant roles in Ethiopian politics.30

Zeleke is also no stranger to the role of online advocacy in promoting political change. Drawing inspiration from online activism during the Arab Spring in 2011, he organized online campaigns against the EPRDF. “We organized a movement which means ‘Enough’ in Amharic, to do similar things on social media,” he said.

Despite Zeleke’s history of political involvement, he maintains that GLEAN is politically independent, self-funded, and does not work formally with the Ethiopian government.31 He had taken a break from activism and politics when Abiy started enacting reforms, but returned to prevent what he calls “ethnonationalism” from threatening the political transition.32

GLEAN has an editorial team and strategic documents outlining two “layers” of online action, according to Zeleke. The first focuses on —GLEAN members actively sought out to recruit accounts with many followers to their cause. The second coordinates messaging and shares information. This takes place mainly in Twitter “rooms,” WhatsApp groups, and a workplace management platform called Flock. On these platforms, operators and participants discuss communication strategies and write tweets for campaigns, according to Zeleke.33

“We [GLEAN] created a synergy that attracted more new and young dynamic people who are now in various work groups and focus teams, doing letter campaigns, digital media, editing, organizing, and doing advocacy and outreach,” he said.34

- 1Interviews conducted by authors.

- 2Claire Wilmot, “What’s Happening in Ethiopia?”

- 3Interview conducted by authors.

- 4Interview by authors; copies of 501(c) application reviewed by the authors.

- 5 Current reporting and analysis suggests that the TPLF enjoys significant popular support in Tigray. See: “Ethiopia’s Tigray War: A Deadly, Dangerous Stalemate," Briefing No. 171, Crisis Group, April 2, 2021, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/ethiopia/b171-ethiopias-tigray-war-deadly-dangerous-stalemate; Reuters Staff, “Ethiopia Sees War Ending, EU Complains of Partisan Aid Access,” Reuters World News, December 4, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-ethiopia-conflict-idUKKBN28E140.

- 6Getachew Reda, former communications minister under the EPRDF, now “advisor to the president of Tigray State," is the most influential high-profile member of the TPLF on Twitter, according to our network analysis. His tweets do get picked up and shared by participants in major Tigrayan activist groups, though the content of his tweets (which sometimes claim unverified battlefield successes by the TDF or refute claims of TDF violence) do not usually spark Twitter activist campaigns by the networks we analyzed. However, some members of Tigrayan networks do openly support figures like Getachew Reda. A major node in pro-Tigrayan activist networks (though not a central campaign organizer of either StandWithTigray or Omna Tigray) appears to have encouraged Mr. Reda to take to Twitter back in June of 2020.

- 7Interviews by authors.

- 8lnterview by authors.

- 9 “Ethiopia: Ethnic Federalism and its Discontents," Crisis Group, September 2009, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/ethiopia/ethiopia-ethnic-federalism-and-its-discontents; Interview by authors; Yemane G. Meskel (@hawelti), “‘TPLF Regime Had Pursued Dual Agenda in Ethiopia: I) Maintain Its Monopoly of Political/Economic Power through Subtly-Crafted, Institutionalized Ethnicity; Ii) Opt for Secession - Residual Plan B- in the Event Its Stranglehold on Exclusive Power Was Threatened or Became Untenable,’” Twitter, March 30, 2021, https://twitter.com/hawelti/status/1376924163663921152.

- 10Awol Allo, “How Abiy Ahmed’s Ethiopia-First Nationalism Led to Civil War,” Al Jazeera, November 25, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2020/11/25/how-abiy-ahmeds-ethiopia-first-nationalism-led-to-civil-war.

- 11Addisu Lashitew, “How to Stop Ethnic Nationalism From Tearing Ethiopia Apart,” Foreign Policy, February 11, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/02/11/ethiopia-how-stop-ethnic-nationalism-conflict-constitution/.

- 12Katharine Houreld and Maggie Fick, “Analysis: How Attempts to Unify Ethiopia May Be Deepening Its Divides, Say Analysts,” Reuters, November 27, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ethiopia-conflict-unity-analysis/analysis-how-attempts-to-unify-ethiopia-may-be-deepening-its-divides-say-analysts-idUSKBN2870PU.

- 13“Hachalu Hundessa - Ethiopia’s Murdered Musician Who Sang for Freedom,” BBC News, July 2, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-53238206.

- 14Interview by authors.

- 15Interviews conducted by author.

- 16“Votervoice Phone Campaign - Act Now!,” Global Ethiopian Advocacy Nexus (GLEAN), 2021, https://www.gleanethiopia.com/.

- 17“About Us,” Global Ethiopian Advocacy Nexus (GLEAN), 2021, https://www.gleanethiopia.com/about/.

- 18lnterviews by authors.

- 19Interviews conducted by authors.

- 20Interview by author.

- 21 “Official Site for Ginbot 7: Movement for Justice, Freedom and Democracy,” Ginbot 7, accessed June 17, 2021, https://www.ginbot7.org/program-3/; Joshua Hammer, “Once a Bucknell Professor, Now the Commander of an Ethiopian Rebel Army,” New York Times, August 31, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/04/magazine/once-a-bucknell-professor-now-the-commander-of-an-ethiopian-rebel-army.html.

- 22 There was a brief period leading up to the 2005 elections where the EPRDF allowed competitive elections and a free press. The result was a much closer election than the EPRDF anticipated, with opposition groups winning all seats in Addis Ababa and dramatically increasing their share of parliamentary seats—from 12 to 174. The EPRDF officially won 371 seats, though opposition parties contested those figures and pushed for re-votes in many areas. International observers also criticized the election for intimidation and irregularities.

- 23 “Ethiopian Protesters ‘Massacred,’” BBC News, October 19, 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/6064638.stm; “Ethiopia: Ethnic Federalism and Its Discontents,” International Crisis Group.

- 24ESAT News, “Berhanu Nega Would Be Based in Eritrea Until Freedom Achieved in Ethiopia: Neamin Zeleke,” TesfaNews, September 21, 2015, https://tesfanews.net/berhanu-nega-to-staye-eritrea-until-freedom-in-ethiopia/.

- 25Douglas Mpuga, “Ethiopian Opposition Group Threatens Armed Resistance,” VOA News, accessed via Internet Archive, July 25, 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20160308170950/http://www.voanews.com:80/content/ethipias-opposition-group-threatens-armed-resistance/2878413.html; Hammer, “Once a Bucknell Professor, Now the Commander of an Ethiopian Rebel Army;” Interview by the authors.

- 26Abdur Rahman Alfa Shaban, “Ethiopia’s Ginbot 7 Dissolves, Transforms into New ‘united’ Party,” Africanews, October 5, 2019, https://www.africanews.com/2019/05/10/ethiopia-s-ginbot-7-dissolves-transforms-into-new-united-party//.

- 27Hammer, “Once a Bucknell Professor, Now the Commander of an Ethiopian Rebel Army;” ESAT News, “Berhanu Nega Would Be Based in Eritrea Until Freedom Achieved in Ethiopia: Neamin Zeleke.”

- 28 “Ethiopia: The Ethiopian Satellite Television media group (ESAT), including objectives and activities in Canada, particularly in the Kitchener-Waterloo area; reports of surveillance by Ethiopian authorities (2012 - March 2016),” Refworld, April 1, 2016, https://www.refworld.org/docid/58944cbe4.html.

- 29Bill Marczak, John Scott-Railton, and Sarah McKune, “Hacking Team Reloaded? US-Based Ethiopian Journalists Again Targeted with Spyware,” The Citizen Lab, March 9, 2015, https://citizenlab.ca/2015/03/hacking-team-reloaded-us-based-ethiopian-journalists-targeted-spyware/.

- 30 For example, former secretary-general of G7, Andargachew Tsige, suggested in a TV interview that he helped facilitate the relationship between Eritrean President Isaiahs Afwerki and Abiy that resulted in the peace deal. Tsige currently serves as CEO of ESAT. The station maintains that it is independent and not-for-profit. Reports indicate it is funded by private donors, though it is unclear who these donors are.

- 31lnterviews conducted by authors.

- 32Interviews conducted by author.

- 33lnterview by authors.

- 34lnterviews by author.

Stage 2: Seeding campaign across social platforms and web

Online campaigns responding to the conflict have coincided with a significant uptick in Twitter use in Ethiopia. Prior to the conflict, Facebook consistently dwarfed Twitter’s approximately 7 percent share of Internet traffic in the country, according to data from StatCounter.1 As the conflict developed, Twitter use skyrocketed, and by March of 2021 Twitter’s share of internet traffic in the country had surpassed Facebook’s, rising to 44 percent, according to analysis conducted by the DFR Lab.2

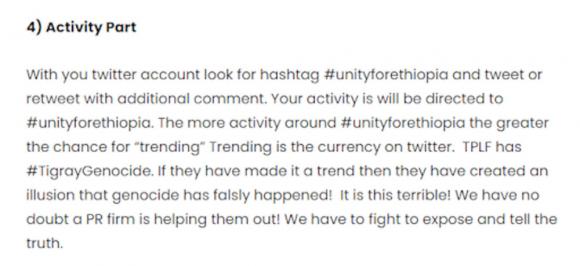

At this stage, a two-way relationship developed between social media campaigns and other forms of media. According to tweets, both sides sought to make their hashtags trend, an example of gaming the algorithm. In the screenshot below (figure 2), UnityForEthiopia, a pro-government account, describes hashtag trending as Twitter’s “currency.”

- 1@DFRLab, “Ethiopian Diaspora Groups Organize Click-to-Tweet Tigray Campaigns amid Information Scarcity,” Medium, April 23, 2021, https://medium.com/dfrlab/ethiopian-diaspora-groups-organize-click-to-tweet-tigray-campaigns-amid-information-scarcity-7e8d7ed73e2f.

- 2@DFRLab, “Ethiopian Diaspora Groups Organize Click-to-Tweet Tigray Campaigns amid Information Scarcity.”

Figure 2: A screenshot from the website created to host UnityForEthiopia’s hashtag campaigns, January 7, 2021. Source: www.unityforethiopia.net/archive

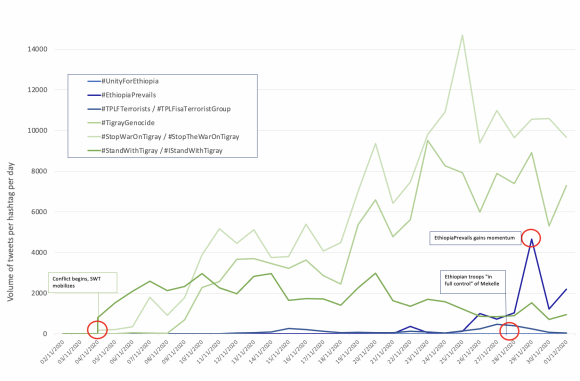

Figure 3: Total volume of tweets per hashtag over time, during the seeding phase. Green trend lines represent pro-Tigray hashtags, whereas the blue trend lines represent pro-government hashtags. Both sides aimed to make their hashtags achieve trending status on Twitter. Twitter's firehose API accessed via AKTEK.

Tigrayan diaspora campaign:

In early November, Tigrayan activists began using Twitter to create and promote hashtags such as #StopTheWarOnTigray, #TigrayGenocide, and #IStandWithTigray, which became part of “copy-and-paste" campaigns promoted on sites like Stand With Tigray (see figure 4 below). These campaigns were responsible for very large volumes of tweets in November, at the earliest stages of the conflict (See figure 3 above for an analysis of tweet volume per hashtag). Moreoever, the use of the word “genocide” in Tigrayan campaigns became a flashpoint for pro-government campaigners responding to the accusation.

Figure 4: Example of a campaign tweet from Stand With Tigray urging participants to use specific hashtags and who to target in their mentions. Source: https://twitter.com/SWTigray/status/1339078254410387457

During the initial information vacuum, Tigrayan campaign participants and operators spread some unverified rumors. Some of these rumors were first posted by TPLF-officials. A prominent example of the spread of false information early in the conflict is the rumour that the Tekeze dam was bombed in early November, which appears to have originated with TPLF leader Debretsion Gebremichael on Tigrayan television networks, which could have been an intentional effort to seed a false narrative.1 There was no evidence the dam was bombed. When telecommunications improved and more reporting became available in late November, media reports began to form the basis of their hashtag campaigns and hearsay or demonstrable false information became less common, according to our analysis. Summaries of reports were circulated as part of copy-and-paste and click-to-tweet campaigns, often tagging accounts perceived to have global influence (see figure 3 above).

Activists took advantage of emerging information and international press to inform their campaigns. For example, following Amnesty International’s report on the Axum massacre, released February 26,2 pro-Tigrayan Twitter accounts amplified it using the hashtag #AxumMassacre. The report confirmed rumours that had been circulating for months—that Eritrean soldiers had massacred hundreds of Tigrayan civilians in the historic city of Axum between November 19 and 29, 2020. According to our data, #AxumMassacre was tweeted nearly 140,000 times in one day in late February, 2021 (see figure 5 below).

- 1Reuters Staff, “Ethiopia Denies Bombing Tigray’s Tekeze Power Dam,” Reuters, November 13, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ethiopia-conflict-dam-idUSKBN27T1HM.

- 2“Eritrean Troops Massacre Hundreds of Civilians in Axum, Ethiopia,” Amnesty International, February 26, 2021, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/02/ethiopia-eritrean-troops-massacre-of-hundreds-of-axum-civilians-may-amount-to-crime-against-humanity/.

Figure 5: Graph depicting the number of tweets about Amnesty International’s Axum report. The blue trend line represents tweets using #AxumMassagre, a pro-Tigrayan hashtag, and the red trend line represents tweets using either #FakeAxumMassacre or #AmnestyUsedTPLFSources, two pro-government hashtags. Twitter's Firehose API accessed via AKTEK.

Pro-government campaign:

From late November onward, pro-government networks promoted hashtag campaigns, while also sharing slogans, government statements, and government-backed fact checks. They also spread media reports that supported their narrative of the conflict, as well as content that accused Tigrayan activists (without evidence) of being part of a massive TPLF disinformation campaign.

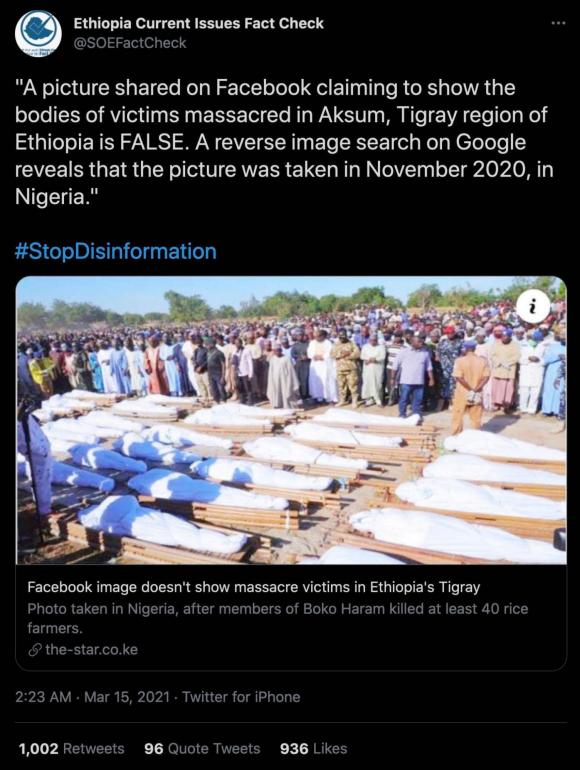

On November 11, 2020, an account called the State of Emergency Fact check (SOEFactCheck) appeared on Twitter.1 Soon after, the government’s spokesperson sent journalists an email urging them to follow the account, stating, “get the latest and fact-based information on the State of Emergency and Rule of Law Operations being undertaken in Tigray Region by the FDRE Federal Government on the official social media accounts.”2 Identical statements were shared by the official account of the Prime Minister’s office.3 The SOEFactCheck account issued government statements and updates on the conflict’s progression, as well as corrective statements in response to media reports and activism (see figure 6 below for example).4

On November 25, the SOEFactCheck account called out an error in a BBC report about the conflict. “We would like to alert all that PM @AbiyAhmedAli has never said these quoted words and hold @BBCMonitoring responsible for spreading disinformation. The tweet has been deleted 4 hours after spreading something that was never said. @BBCWorld.”5 In this case, the BBC had misquoted the Prime Minister. Its Twitter account later wrote, “We have deleted an earlier tweet on Ethiopia which was based on a video clip broadcast on Fana TV this morning which we misreported. We are reviewing what went wrong and offer our sincere apologies for the error.”6

Mistakes by major news outlets strengthened the “disinformation” narrative central to the pro-government campaign. Government supporters also began to capitalize on any example of unverified or false information spread by Tigrayan activists as evidence of TPLF disinformation.

After the ceasefire, the SOEFactCheck account name was changed to the “current issues” fact check.7 It continues to issue statements, many of which are focused on critical media coverage.8

- 1Ethiopia Current Issues Fact Check (@ETFactCheck), “Https://T.Co/ZeE8lC3KfC,” Twitter, November 12, 2020, https://twitter.com/ETFactCheck/status/1326755221905797120.

- 2Email correspondence with authors and journalists.

- 3 Office of the Prime Minister - Ethiopia (@PMEthiopia), “Get the latest and fact based information on the State of Emergency and Rule of Law Operations being undertaken in Tigray Region by the FDRE Federal Government on the official social media accounts: Facebook Page: Twitter: @SOEFactCheck,” Twitter, November 11, 2020, https://twitter.com/PMEthiopia/status/1326392800649338880?s=20.

- 4 Ethiopia State of Emergency Fact Check@SOEFactCheck, “On the Basis of the Decision of the House of Federation and the Council of Ministers Regulation ‘Concerning the Provisional Administration of the Tigray National Regional State’, Dr. Mulu Nega Has Been Appointed as the Chief Executive of the Tigray Regional State,” Twitter, November 13, 2020, https://twitter.com/SOEFactCheck/status/1327118135057584128; Ethiopia State of Emergency Fact Check (@SOEFactCheck), “ENDF Takes Full Control of Axum, Adwa and the Surrounding Areas of Adigrat.,” Twitter, November 20, 2020, https://twitter.com/SOEFactCheck/status/1329832359655583750.

- 5Ethiopia State of Emergency Fact Check (@SOEFactCheck), “We would like to alert all that PM @AbiyAhmedAli has never said these quoted words and hold @BBCMonitoring responsible for spreading disinformation. The tweet has been deleted 4 hours after spreading something that was never said. @BBCWorld,” Twitter, November 25, 2020, https://twitter.com/SOEFactCheck/status/1331595269855711233?s=20.

- 6BBC Monitoring (@BBCMonitoring) “We have deleted an earlier tweet on Ethiopia which was based on a video clip broadcast on Fana TV this morning which we misreported. We are reviewing what went wrong and offer our sincere apologies for the error,” Twitter, November 25, 2020, https://twitter.com/BBCMonitoring/status/1331607855343034369?s=20.

- 7Ethiopia Current Issues Fact Check (@ETFactCheck), Twitter, https://twitter.com/ETFactCheck.

- 8Ethiopia Current Issues Fact Check (@ETFactCheck), “Highlighting the unfair and orchestrated international media attacks on Ethiopia: a country of over 100 million,” Twitter, August 11, 2021, https://twitter.com/ETFactCheck/status/1425381901632745478?s=20.

Figure 6: Example of an SOE fact check tweet. Source: https://twitter.com/SOEFactCheck/status/1371346305730088962

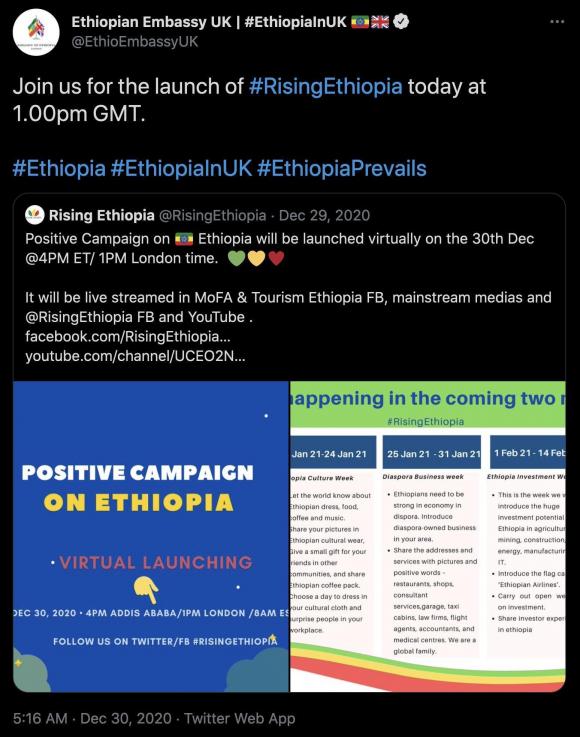

Initially, pro-government campaigns mimicked Tigrayan campaigns, and set up to host click-to-tweet campaigns.1 One major hashtag campaign launched early on was #EthiopiaPrevails, which first appeared on Twitter on November 15, alongside #UnityForEthiopia, which predates the conflict but has been a consistent hashtag used by government supporters. As the conflict progressed new hashtags appeared, such as #TPLFisTheCause, which were picked up and circulated by official government accounts, Ethiopian ambassadors (see figure 7 below), and some media outlets.2

- 1Unity for Ethiopia: Home, https://www.unityforethiopia.net/.

- 2 Billene ቢልለኔ Aster Seyoum (@BilleneSeyoum), “In 2018 & 2019 Alone TPLF Recruited and Trained 47,173 & 37,373 Militia Members Respectively, Illegally Commanding an Irregular Militia Force of the More than 170,000 Members Preparing Them to Attack Unseat the Federal Government #TPLFisTheCause…” Twitter, February 10, 2021, https://twitter.com/BilleneSeyoum/status/1359582835649183749; Ethiopia Current Issues Fact Check (@ETFactCheck), “ይህ ገጽ ከዚህ በኋላ ትግራይን ጨምሮ በመላው ኢትዮጵያ ወቅታዊ ሁኔታዎች ላይ ያተኮሩ መረጃዎችን የሚያጣራና የሚያጋራ ይሆናል። This page will now focus on addressing current issues in Ethiopia including Tigray,” Twitter, July 9, 2021, https://twitter.com/SOEFactCheck/status/1413409732736471044?s=20; Billene ቢልለኔ Aster Seyoum (@BilleneSeyoum), “Discussion on the Rule of Law Operation in Tigray Https://T.Co/Rd0w6Iivqg Context Is Always Critical in Any Analysis and Reporting on #Ethiopia. #EthiopiaPrevails #EndTPLFImpunity #JusticeForMaikadra,” Twitter, November 25, 2020, https://twitter.com/BilleneSeyoum/status/1331498382645469184.

Figure 7: Example of the Ethiopian embassy in the UK using one of the pro-government hashtags that began circulating at the beginning of the conflict. Source: https://twitter.com/EthioEmbassyUK/status/1344225829165936640

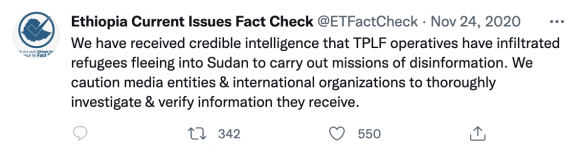

Another key tactic of pro-government campaigners was to undermine witness credibility. This tactic was first observed in online discourse as early as late November, but the narrative deepened and gained momentum after a cascade of critical media reports in early 2021. Disturbing reports from international media based on refugee testimony in Sudan in November1 prompted a response by the SOE Fact Check, which issued a statement claiming that refugees being interviewed by international media were TPLF operatives (see figure 8 and 9 below).2

- 1“Heartbreaking Stories from Refugees Fleeing Ethiopia Violence,” UN News, November 19, 2020, https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/11/1078132; Mohammed Amin, “Tigray Refugees Recount the Horrors of Ethiopia’s New Conflict,” The New Humanitarian, November 19, 2020, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2020/11/19/ethiopia-tigray-conflict-sudan-refugees.

- 2 Ethiopia State of Emergency Fact Check (@SOEFactCheck), “We Have Received Credible Intelligence That TPLF Operatives Have Infiltrated Refugees Fleeing into Sudan to Carry out Missions of Disinformation. We Caution Media Entities & International Organizations to Thoroughly Investigate & Verify Information They Receive,” Twitter, November 24, 2020, https://twitter.com/SOEFactCheck/status/1331261456617234432.

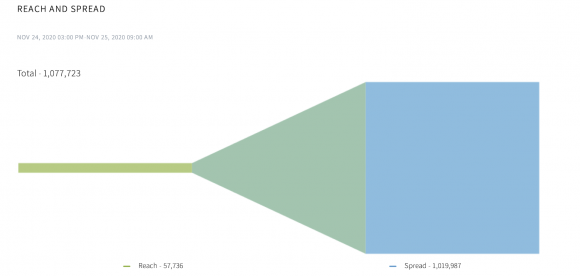

Figure 8: The SOEFactCheck account’s initial tweet seeding the narrative about refugees and journalists’ sources being infiltrated by the TPLF. Source: https://twitter.com/SOEFactCheck/status/1331261456617234432

It was picked up and circulated by government support networks, quickly reaching an audience that exceeded anything the “fact check” account had produced to that point. The government provided no evidence to substantiate these claims. It subsequently claimed that all refugees were young men, and therefore TPLF militants.1 UNHCR data on refugee demographics showed 45 percent were children and 43 percent were women.2 The government later took steps to prevent refugees from accessing routes into Sudan.3 These messages served to pre-emptively undermine the credibility of reporting on the degree of violence and civilian suffering recounted by non-government sources.4

The belief that the TPLF are posing as victims of violence to misinform the world became a central theme in pro-government discourse throughout the conflict.5 The most notable example of this came in the aftermath of Amnesty International’s report on the massacre of Tigrayan civilians in Axum. Pro-government accounts pushed the notion that TPLF had infiltrated the media and biased the report, gaining traction with hashtags like #FakeAxumMassacre and #AmnestyUsedTPLFSources. Although they achieved fewer overall tweets than the opposing Tigrayan hashtags sharing the content of the report, our analysis shows that pro-government accounts tend to have higher follower counts than Tigrayan accounts and are therefore able to reach a larger audience with fewer tweets (see figure 9 above).

Government supporters also shared information from state-affiliated media outlets as part of their campaigns. Information spread by government supporters was also sometimes traded up the chain and circulated by government officials and state-owned media. The Ethiopian state plays a major role in the media landscape in the country, directly owning at least a third of all broadcast media.6 Moreover, some media outlets that appear privately owned are actually funded by parastatals managed by regional governments, according to a report by the European Institute of Peace.7

Efforts to undermine critical reporting were also employed. Following Amnesty’s Axum report, for example, the state-affiliated Ethiopian News Agency (ENA) interviewed an investigative journalist who claimed that one of Amnesty’s witnesses was named Michael Berhe, and that he had not been in Axum at all – claiming that he was really a man based in Boston pretending to be a priest.8 That same day, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church Archdiocese of New York confirmed to FANABC—Ethiopian state TV—that Berhe was not a priest, but a man working as an interpreter in Boston.9 Researchers with Amnesty say they never spoke to Berhe, and that he was not one of the witnesses in the report.10 Nevertheless, the “fake priest” , which began on state media made its way to Twitter,11 resulting in government supporters incorporating the hashtags #ShameOnAmnesty and #AmnestyUsedTPLFsources in their click-to-tweet campaign (see figure 10 below for an example).12

A blog post citing the “fake priest” narrative was even shared in a (now deleted) tweet by the official Ministry of Foreign Affairs account.13 Leaked government documents from early March show that Ethiopia’s Foreign Affairs Ministry was instructed to explore options to have him arrested and tried for crimes against the Ethiopian state.14

- 1 Office of the Prime Minister - Ethiopia (@PMEthiopia), “Reports Indicate That Refugees in Sudan Are Mostly Male, as Opposed to Women and Children. Who Are These Male Youth? If the Youth Are Part of Those Who Massacred Innocent Civilians in Maikadra, Then They Need to Brought to Justice. #PMAbiyResponds #EthiopiaPrevails,” Twitter, November 30, 2020, https://twitter.com/PMEthiopia/status/1333352269920817153.

- 2“Sudan Eastern Border: Update on Daily New Arrivals from Ethiopia,” UNHCR Operational Data Portal (ODP), accessed August 20, 2021, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/dataviz/144.

- 3Nic Cheeseman and Yohannes Woldemariam, “Ethiopia’s Perilous Propaganda War,” Foreign Affairs, April 8, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/africa/2021-04-08/ethiopias-perilous-propaganda-war; Samuel Gebre and Claire Wilmot, “A Glimpse into the Future of Government Propaganda,” The Mail & Guardian, December 8, 2020, https://mg.co.za/africa/2020-12-08-a-glimpse-into-the-future-of-government-propaganda/.

- 4 Abdi Latif Dahir, “‘I Miss Home’: In Tigray Conflict, Displaced Children Suffer,” New York Times, December 20, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/20/world/africa/tigray-ethiopia-sudan-refugees.html; Will Brown, “‘Please, We Need Help’: Searching for Their Families, Ethiopian Refugees Mass on Sudanese Border,” The Telegraph, November 25, 2020, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/11/25/please-need-help-searching-families-ethiopian-refugees-mass/.

- 5GLEAN - Global Ethiopian Advocacy Nexus (@GleanEthiopia), “The #TPLFisaTerroristGroup agents in @AmnestyEARO destroyed @amnesty's reputation by releasing a report based on unsubstantiated claims hoping people won't read beyond the disturbing headline they used to misinform the world. #EthiopiaPrevails @UN_HRC @mbachelet @POTUS,” Twitter, February 28, 2021, https://twitter.com/GleanEthiopia/status/1366011810034442242?s=20.

- 6“Fake News Misinformation and Hate Speech in Ethiopia: A Vulnerability Assessment,” European Institute of Peace, pg.6, pg.9, April 12, 2021, https://www.eip.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Fake-News-Misinformation-and-Hate-Speech-in-Ethiopia.pdf.

- 7 “Fake News Misinformation and Hate Speech in Ethiopia: A Vulnerability Assessment,” European Institute of Peace.

- 8“Amnesty Int’l Witness Not Priest but Imposter, Says Investigative Journalist,” Ethiopian News Agency, February 27, 2021, https://www.ena.et/en/?p=22049. The source for this claim appears to be a YouTube channel run by former ESAT journalist Dereje Habtewold.

- 9“Archdiocese of EOC Says Imposter Amnesty International Witness Not Follower of Church,” Fana Broadcasting Corporate, February 27, 2021, https://www.fanabc.com/english/archdiocese-of-eoc-says-imposter-amnesty-international-witness-not-follower-of-church.

- 10 Jean-Baptiste Gallopin (@jbgallopin), “Dude. We Didn’t Talk to the Guy,” Twitter, February 26, 2021, https://twitter.com/jbgallopin/status/1365368353452421130.

- 11 Ministry of Foreign Affairs Ethiopia (@MFAEthiopia), “#Ethiopia: Lies, Damn Lies, #Axum and the #West,” Twitter, accessed via web archive, March 5, 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/20210305162451/https://twitter.com/mfaethiopia/status/1367870896938029056.

- 12“Amnesty International Is Not Willing To Use Credible Ethiopian Source!,” Rising Ethio, February 26, 2021, https://risingethio.com/amnesty-international-is-not-willing-to-use-credible-ethiopian-source/.

- 13 Ministry of Foreign Affairs Ethiopia (@MFAEthiopia), “#Ethiopia: Lies, Damn Lies, #Axum and the #West.”

- 14 Zecharias Zelalem (@ZekuZelalem), “But This Leaked Doc (Translation Included) Reveals That on March 3, the @mfaethiopia’s International Legal Affairs Director Yanit Abera Habtemariam, Was Instructed to Explore Options to Have Michael Berhe Extradited & Tried for Crimes against the Ethiopian State. @AmnestyEARO Https://T.Co/22NOVgvw7r,” Twitter, April 1, 2021, https://twitter.com/ZekuZelalem/status/1377657787732344836.

Figure 10: Example of the “fake priest” narrative circulating in pro-government networks. Source: https://twitter.com/eliasamare/status/1365846893025058816

In reality, Berhe does work as an interpreter in Boston but he never spoke with Amnesty, nor has he ever claimed to be a priest. He became the subject of this controversy by agreeing to take part in a clearly labelled re-enactment video directed by the SWT Campaign, where volunteers read dramatized scripts based on testimony from Tigrayan victims of violence reported in the media, according to interviews with the SWT campaign organizers.1 Somehow, possibly because the video was released immediately before the Amnesty report and because it discussed the Axum massacre, the two were linked in government supporter circles.

There is also evidence that false personas were used to spread pro-government messaging. For example, one particular impersonator account known as “George Bolton UN,” who described himself as a “Political analyst, humanitarian, diplomacy, former United Nations,” gained significant traction in pro-government circles (figure 11 below). Bolton’s tweets in support of the Ethiopian government were picked up by a former ESAT journalist before making their way to multiple Ethiopian state-affiliated media outlets.2 The account is now suspended.

- 1 “We felt like we were doing really good with the art and the costumes and stuff, but we didn’t imagine that the Ethiopian Foreign Ministry would respond to our video,” said Lwam Gidey in an interview conducted by the authors. “We wanted the re-enactment video to be a voice for victims, that was our goal. But it was also to humanize the conflict—we wanted people to see that these victims are human beings and they have families, they have stories, and cultures.”

- 2Zecharias Zelalem (@ZekuZelalem), “Meanwhile...Former ESAT Journalist Dereje Habtewold Is among Those Duped, Sharing the Screenshot and Amplifying the Message Yesterday to His 130k Facebook Followers. The Power of AI......Is on Par with That of Balding Middle Aged White Male Retirees in Suits. Https://T.Co/HhzTr0oDoQ,” Twitter, March 9, 2021, https://twitter.com/ZekuZelalem/status/1369207643752050690; Zecharias Zelalem (@ZekuZelalem), “Despite This....the @PressEthio’s English, Amharic and Tigrigna Language Facebook Pages...Which Combined Have about 400,000 Followers...Currently Have This Fabricated Account’s Tweet Pinned to the Top of Their Pages. Tax Payer Funded Media, Let Me Remind You. Https://T.Co/9tVKRxF8MK,” Twitter, March 9, 2021, https://twitter.com/ZekuZelalem/status/1369184551575109632.

Figure 11: Screenshot from the now-deleted twitter account @GboltonUK. Source: https://web.archive.org/web/20210309194951/https://twitter.com/gboltonun.

Stage 3: Responses by industry, activists, politicians, and journalists

The extent to which Tigrayan or pro-government campaigns influenced international discourse is unclear. Both click-to-tweet campaigns tagged US and other international policymakers and media in their tweets, but the majority did not engage.

International media outlets such as Al Jazeera1 and France 242 invited campaign operators and participants from both campaigns to participate in live discussions alongside journalists. Journalists and researchers were accused of partisanship, and both campaigns sought to incorporate research and reporting favourable to their narratives into their campaigns.

From February onward however, reporting from reputable news sources and human rights organizations lent support to claims that atrocity crimes were being committed in Tigray.

Pro-government campaigns sought out bloggers, journalists, and academics sympathetic to their narrative to combat the effects of these reports. In March, Zeleke said GLEAN was working on assembling an op-ed and writer’s team that would include academics and veteran activists. “We are working on research and development to focus on the past 27 years of TPLF crimes,” he said.3

It is unclear whether political adoption occurred directly from these campaigns. Some minor political actors globally have adopted the language of genocide to describe the conflict, though it is unclear whether this language came from the pro-Tigray social media campaigns that have urged the use of that term.4

The Ethiopian government believes that of the Tigrayan activist campaign has taken place, however. When asked what evidence the government is using to assess the existence, prevalence, and effects of TPLF disinformation online, the Prime Minister’s spokesperson, Billene Seyoum, said by email that “thousands of Twitter accounts claimed ‘genocide’ as early as November 11, 2020, when Rule of Law operations began on November 4, 2020.” Understanding this Twitter activity as “activism,” she added, “rather than an organised disinformation campaign is problematic, as the community being influenced have taken on that [genocide] narrative without evidence to that effect.”5

Genocide is a legal determination that has not been formally made in relation to this conflict. News reports and U.S. diplomatic sources suggest that ethnic cleansing has taken place in parts of Tigray, however.6 Other groups in Ethiopia also use the claim of genocide to draw attention to violence against their communities.7

In late March, the Ethiopian government confirmed reports that Eritrean troops were involved in the conflict and were committing atrocity crimes—allegations that had been circulating since December 2020.8 Several high-profile Eritrean Twitter accounts joined the pro-Ethiopian government Twitter campaigns at this time (see figure 12 below).9 For example, #ScapegoattingEritrea became a prominent hashtag in the aftermath of human rights reports or media reports detailing Eritrean troops committing atrocities against civilians.10

- 1“Ethiopia: What is starvation stalking Tigray?” Al Jazeera Stream, January 30, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/program/the-stream/2021/1/30/will-a-humanitarian-crisis-destroy-tigray.

- 2“Which Way for Ethiopia? Abiy cracks down on regional revolts ahead of elections,” France 24, June 3, 2021, https://www.france24.com/en/tv-shows/the-debate/20210503-which-way-for-ethiopia-abiy-cracks-down-on-regional-revolts-ahead-of-elections.

- 3Interview conducted by authors.

- 4Mick Wallace (@wallacemick), “There's little doubt but #AbiyAhmedAli would not dare speak in these terms if he did not already have the support of World Powers - He's no longer hiding his desire for Genocide against the people of #Tigray… Quote Tweet,” Twitter, July 19, 2021, https://twitter.com/wallacemick/status/1417106315650928641?s=20.

- 5Billene Seyome, email correspondence with Claire Wilmot, June 29, 2021.

- 6“In Pictures: Land Dispute Drives New Exodus in Ethiopia’s Tigray,” Al Jazeera, March 31, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2021/3/31/land-dispute-drives-new-exodus-in-ethiopias-tigray; Declan Walsh, “Ethiopia’s War Leads to Ethnic Cleansing in Tigray Region, U.S. Report Says,” New York Times, February 26, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/26/world/middleeast/ethiopia-tigray-ethnic-cleansing.html; In contrast to genocide, ethnic cleansing is not a legal category, but emerged to describe efforts to render particular areas ethnically homogenous during the conflict in the former Yugoslavia; Reuters Staff, “Ethiopia Rejects U.S. Allegations of Ethnic Cleansing in Tigray,” Reuters, March 13, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-ethiopia-conflict-idUSKBN2B50ES.

- 7OromoGenocide and AmharaGenocide have also been used in online campaigns.

- 8Up until this point Eritrean military involvement in the Tigray region was plausibly deniable. At the end of January, Associated Press reported an increase of diplomatic pressure being leveraged at high levels by the United States for Eritrea to withdraw its troops from Ethiopia. See: “Ethiopia PM Abiy Ahmed admits Eritrea forces in Tigray," BBC, March 23, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-56497168.

- 9 In addition to Twitter activity by the Eritrean diaspora and government supporters, several articles on the conflict were published on English-language Eritrean news sites. In Eritrea, however, there is no media that can be considered separate from the state, according to research and reporting. A number of frequent authors on Eritrean media platforms are also central nodes in Eritrean Twitter campaigns, particularly those that overlap with Ethiopian networks.

- 10Awit (@EriZara3), #EU’s Hypocrisy is beyond measure. As if it isn’t tacitly blessing rights abuses worldwide & financed & enabled #TPLFcrimes in #Ethiopia #Eritrea & #Somalia for 3decades, here it is #ScapegoatingEritrea. Deplorable @EU_Commission @Haavisto #EritreaPrevails #TPLFLies #Axumfiction,” Twitter, March 22, 2021, https://twitter.com/EriZara3/status/1374034012210094085?s=20.

Several of the individuals behind these accounts have links to Eritrea’s ruling party, the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ), and the young wing in the diaspora.1 Some accounts in the Eritrean networks list shabait.com as their website in their Twitter bios, which is the website of the Eritrean Ministry of Information, and have had their work shared by the Eritrean Minister of Information.2 Zeleke said that the interactions with Eritrean social media campaigns are largely informal. “There are some issues where we have common interests and others that are not common, but there is cooperation and communication,” he said.

- 1Mike ኤርትራዊ (@EllamellaMg), “Bidhho tour Frankfurt Germany #Eritrea #IStandwithEritrea #YPFDJ,” Twitter, December 4, 2016, https://twitter.com/EllamellaMg/status/805521085840183297?s=20; Mike ኤርትራዊ (@EllamellaMg), “#Eritrea #YPFDJ #PFDJ wdbna,” Twitter, April 19, 2021, https://twitter.com/EllamellaMg/status/1119189163113353216?s=20.

- 2#InvestInEritrea (@DahlaKib), https://twitter.com/DahlaKib; Simone K Hagos (@tewerwari_1), https://twitter.com/tewerwari_1; Yemane G. Meskel (@hawelti), “Red Sea Institute offers refreshing perspectives on important Eritrean issues through meticulous research & objective/dispassionate analysis,” Twitter, August 26, 2014, https://twitter.com/hawelti/status/504273072044924929?s=20.

Stage 4:

and reports from groups were the most effective attempts at mitigating the impacts of the government’s media campaign. From February, media and rights groups reported that massacres, conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV), and significant amounts of destruction had taken place in Tigray, and that civilians were facing extreme levels of suffering.1 International pressure on the Ethiopian government to allow for unfettered humanitarian access and independent investigations increased during this period, particularly after the Axum massacre.2

On February 24, the Prime Minister’s Office announced that journalists from seven international media outlets would be permitted to access the region.3 However, after granting access, several journalists, fixers, and translators working with foreign media were arrested before being released without charge.4 Several foreign journalists were subsequently expelled from the country.5 After the TDF recaptured Mekelle at the end of June, 15 journalists were arrested, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.6 Arrests, attacks, and of journalists has been a consistent feature of the conflict—a significant turn of events for a government that was initially celebrated for its commitment to press freedom.7 In August, at the time of writing, another internet and communications blackout persisted across Tigray.8

Mitigating Each Other

The competing campaigns attempted to use mitigation efforts against each other, employing tactics such as calling on their participants to engage in community mitigation, mass reporting (flagging) accounts, accusing the opposing campaign of disinformation, as well as appearing to cut off access to sites when possible.

Allegations of TPLF disinformation became a central feature of the Ethiopian government’s official communications at this stage. In late February, prior to the release of Amnesty International’s report on the Axum massacre, the Prime Minister’s Office issued a statement that warned of "overt and covert misinformation campaigns” by the “criminal clique”9 TPLF, which it claimed was using its “well-financed networks abroad” to use digital and other forms of media to portray exaggerated or misleading accounts of the conflict. A day later, Stand With Tigray’s web traffic dropped to zero within Ethiopia, suggesting that the site had been blocked in Ethiopia.10 Omna Tigray’s site was also inaccessible in Ethiopia on March 22, and access disruptions began several days earlier, on March 19, according to site stats shared by Omna Tigray members. Both organizations have encouraged participants within Ethiopia to use VPNs to access their sites and campaigns, according to operators from both Stand With Tigray and Omna Tigray.11

Tigrayan activist networks reported spending more time pushing back against efforts by government supporters to undermine their activism and critical reporting of atrocities being committed in Tigray. “I would say that for every breaking news story that came out about atrocities in Tigray there was some counter-story that we had to spend time to debunk” said one activist, who wished to remain unnamed.12

“It’s exhausting,” said a woman who organizes campaigns with Omna Tigray. “I lost my cousin in a massacre in my hometown by Eritrean soldiers, and when I was talking about that online, government supporters were telling me that the massacre was fake. There is some kind of emotional struggle—you know you’ve lost someone, but people are telling you ‘it’s just fake news.’”13

Calls to identify inauthentic accounts

The rapid growth in Twitter activity generated by both campaigns led to accusations that participation was artificially inflated by the use of automated accounts. In December, voices critical of the TPLF and those targeted by “click-to-tweet” campaigns began to call for investigations into automated “bots” and other forms of inauthentic behaviour (see figure 13 below for an example).14

- 1Buildings belonging to NRC destroyed in Ethiopia's Tigray,” Norwegian Refugee Council, February 8, 2021. https://www.nrc.no/news/2021/february/buildings-belonging-to-nrc-destro….

- 2Laeticia Bader, “Interview: Uncovering Crimes Committed in Ethiopia’s Tigray Region,” Human Rights Watch, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/12/23/interview-uncovering-crimes-committ…; “Ethiopia: Tigray Region Humanitarian Update,” Situation Report (Ethiopia: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, November 21, 2020), https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/ethiopia-tigray-region-humanitari…; Jeffrey James, “Ethiopia’s Tigray Conflict and the Battle to Control Information | Abiy Ahmed News | Al Jazeera,” Al Jazeera, February 16, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/2/16/ethiopias-tigray-conflict-and-….

- 3Prime Minister’s Office Statement, Ethiopia, February 24, https://twitter.com/PMEthiopia/status/1364553457802297344/photo/2; David Pilling, “FT Translator and Others Released in Ethiopia,” Financial Times, March 3, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/5fc591d4-c39d-41cc-b777-8a4227b6b8ee.

- 4Reuters Staff, “Three Workers for Foreign Media Arrested in Ethiopia’s Tigray Region,” Reuters, March 2, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ethiopia-conflict-journalists-idUSKC….

- 5Bloomberg Africa (@BBGAfrica), “Ethiopia deported Simon Marks, a journalist who had been reporting for Bloomberg News and other media organizations about developments in Africa’s second-most populous nation including a civil war in the northern Tigray region,” Twitter, May 23, 2021, https://twitter.com/BBGAfrica/status/1396399779517812738?s=20.

- 6CPJ Africa (@CPJAfrica), “Today is day three that 15 journalists who were arrested last week are being held incommunicado in #Ethiopia. Their lawyer, Tadele Gebremedhin, has told @pressfreedom that he & family members remain in the dark. We urge authorities to immediately disclose their whereabouts,” Twitter, July 5, 2021, https://twitter.com/CPJAfrica/status/1412119518617522177?s=20.

- 7“At Least Six Ethiopian Journalists Arrested in Past Six Days,” Reporters without borders (RSF), November 13, 2020, https://rsf.org/en/news/least-six-ethiopian-journalists-arrested-past-s…; Salem Solomon, “Ethiopian Journalist Attacked in Her Home, Questioned on Tigray Connections,” Voice of America, February 12, 2021, https://www.voanews.com/press-freedom/ethiopian-journalist-attacked-her…; “New Era for Ethiopia’s Journalists,” Reporters Without Borders (RSF), April 4, 2019, https://rsf.org/en/news/new-era-ethiopias-journalists.

- 8Declan Walsh, “On the Scene: A Turnabout in the Tigray War,” New York Times, July 2, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/07/02/world/africa/ethiopia-ti…

- 9 Office of the Prime Minister - Ethiopia (@PMEthiopia), “Updates on Tigray Region #PMOEthiopia Https://T.Co/B3uccBVwBc,” Twitter, February 24, 2021, https://twitter.com/PMEthiopia/status/1364553457802297344.

- 10SWT was averaging about 3000 visits per day from Ethiopia, according to the website’s stats counter, and plummeted to zero on February 25.

- 11Interviews conducted by authors.

- 12Interviews conducted by authors..

- 13Interviews conducted by authors...

- 14Bronwyn Bruton (@BronwynBruton), “Request for Assistance: Looking for Evidence of #TPLF Disinformation Campaigns. This Means -- Fake Accounts, Identical Tweets Coming from Multiple Users, Etc. - Not Just One Person Making Stuff up/Exercising Poor Judgment. Tweet/DM Me. Thanks!,” Twitter, January 11, 2021, https://twitter.com/BronwynBruton/status/1348689523224489984.

Figure 13: Tweet by Neamin Zeleke alleging the use of bots by pro-TPLF organizers to mislead the public. Source: https://twitter.com/NeaminZeleke/status/1343424717185822720

Investigations found no evidence of the use of automation in either campaign.1 Twitter defines mass copy-and-paste campaigns (which it calls “copypasta”) as a form of platform manipulation and sometimes limits visibility of these tweets or suspends accounts that participate too frequently.2

In the spring of 2021, the authenticity of older accounts with larger followings involved in the campaigns was also called into question. Participants created accounts claiming to be diplomats, UN officials, or foreign affairs experts. These accounts reportedly used images generated by artificial intelligence to impersonate experts, such as the "George Bolton" figure referenced above. members of different races and communities.3 Examples of these accounts can be found in both campaigns, but they had a greater role and impact in pro-government networks, according to our analysis. Some account operators changed their allegedly AI generated photos when confronted on Twitter,4 but others maintained the persona.5

Mass Twitter reporting from both sides

Around December 2020, campaign operators and participants began mass reporting the other side’s accounts on Twitter. Conversations in a group hosted by government-supporting activists show that members encouraged each other to go through the follower lists of groups like SWT and OmnaTigray to find people to report.6 Accounts in Tigrayan networks were also subject to and hacking threats and attempts, some of which were successful, according to Tigrayan activists and discussions observed on Twitter and in a pro-government telegram group.7

We also observed members of the Tigrayan networks encouraging followers to report government supporting accounts to Twitter.8 Tigrayan activists confirmed that they engaged in mass reporting of adversarial users, with some of the effort organised on Twitter itself. Mass reporting did disrupt government campaign networks—several key “nodes” were taken down for weeks, which reduced the reach of their campaigns, but supporters engaged with Twitter Support to reinstate them.

Platform mitigation

Based on discussions observed on the platform, interview testimony, as well as videos released by Stand With Tigray, it appears Twitter began to take a more active approach to suspending accounts engaging in copy-and-paste campaigns or tweeting too frequently in February and March.9 We reached out to Twitter to ask whether its strategy or tactics for moderating content around Ethiopia had changed since the start of the conflict. A Twitter spokesperson did not answer the question directly, but said that the company is “continuously working to address inauthentic and harmful behaviour” everywhere through its policies.10

Content moderation appears to have occured on other social media platforms too: the Ethiopian government was linked to inauthentic accounts on Facebook, which were removed on June 12. Facebook stated it had removed a “network of accounts, pages, and groups in Ethiopia for coordinated inauthentic behaviour,” which it linked to INSA.11 The network was primarily sharing information in Amharic, and focused on “current events” in Ethiopia, but Facebook assessed that this activity “was not directly focused on the Tigray region or the ongoing conflict in Tigray” but sought to promote Abiy’s Prosperity Party more broadly.12

- 1Claire Wilmot, “What’s happening in Ethiopia;” Alexi Drew and Claire Wilmot, “What’s happening in Tigray," Washington Post, February 5, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/02/05/ethiopias-digital-ba….

- 2Twitter Comms (@TwitterComms), “We’ve seen an increase in ‘copypasta,’ an attempt by many accounts to copy, paste, and Tweet the same phrase. When we see this behavior, we may limit the visibility of the Tweets,” Twitter, August 26, 2020, https://twitter.com/TwitterComms/status/1298810494648688641?s=20.

- 3Geoffrey York and Zecharias Zelalem, “Tigray Conflict Sparks a War of Fake Tweets and Intense Propaganda,” The Globe and Mail, April 1, 2021, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/world/article-tigray-conflict-sparks-a-….

- 4Zecharias Zelalem (@ZekuZelalem), “She Certainly Is Beautiful. If Only She Actually Existed. The Individual Who Runs the @LanderMiddle Account Purchased a Fake Generated Face, via an Avatar Developer Website. The Person Tweeting Could Be as Bearded as Me. Read about It from @NYTimes. Https://T.Co/OuKqbb3acg Https://T.Co/9CCq16cfNK,” Twitter, January 12, 2021, https://twitter.com/ZekuZelalem/status/1348863453625253889?s=20.

- 5“Dr. Ir. Middle Lander (@LanderMiddle)” Twitter, accessed June 30, 2021, https://twitter.com/LanderMiddle.

- 6Among the targets of these mass reporting campaigns were prominent Ethiopian and foreign journalists covering the conflict, researchers and analysts, as well as major activist nodes in the Tigrayan advocacy networks.

- 7Wedi Se'are Mekonnen (@himbashagos), “To the a**hole who hacked my account, altered my profile info., & cleared my 300+ Tigray posts, karma will come back to you full force. You didn't break my spirit. I am back & ready to post about the #TigrayGenocide. Even if I have to start from scratch. - 4/8/2021,” Twitter, April 9, 2021, https://twitter.com/himbashagos/status/1380376133544210434?s=20; Yirga GebreMedhin Tsegay(HaHu) (@DailyHaHu), “Yesterday they tried to hack my Facebook account, but they can't & Today My Account has been disabled. I have submitted a review for @Facebook. ኣይኮነን ፌስቡክ ሂወትና ቀቲሎም ከም ዘይስዕሩና ኣይተረድኦምን!! ክንዕወት ኢና። #Tigray will prevail!!” Twitter, April 14, 2021, https://twitter.com/DailyHaHu/status/1382286433562603521?s=20.

- 8SAS#FreeTigray! (@2010ySas), “How foolish could be to report this? Don't you feel shame to accelerate #TigrayGenocide? @Twitter, should to take actions in suspending his account. This is 21st century, #Tigray people's life matters and your master is a war criminal @AbiyAhmedAli. @MOusmanova,” Twitter, February 22, 2021, https://twitter.com/2010ySas/status/1364005364497145859?s=20; Ethiopia ፐwєєተร (@Ethiopia_Abebe) An Amhara/Eritrean spy pretending to be a white woman to discredit the #TigrayGenocide awareness campaign. #1⃣ All Tegaru please do not reply, retweet, or like this fake account. #2⃣ Report it as spam/fake account and block immediately!” Twitter, June 25, 2021, https://twitter.com/Ethiopia_Abebe/status/1408435726757339140?s=20.

- 9SWT Media, ትዊተር ኣካዊንትኩም ዝዕፀወሉ 5 ምክንያታት | 5 Reasons Why Your Account Gets Suspended on Twitter | #TweetForTigray ( , 2021), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i2r1io6rO7A&t=156s; Iyoba 🇪🇹 🟩🟨🟥 🇪🇹(@iyoba4u), “We Urge @Twitter to Kindly Lift the Suspension of @assefa_h’s Twitter Account, Who Is Fighting for Human Rights and Freedom of Speech. Thank You Cc: @jack @TwitterSupport @Twitter @TwitterSafety @TwitterAPI @TwitterEng @nickpickles @yoyoel @Policy @TwitterGov,” Twitter, March 11, 2021, https://twitter.com/iyoba4u/status/1370102379820032006; Iyoba 🇪🇹 🟩🟨🟥 🇪🇹(@iyoba4u), “No Suspicious Activities Were Made by This Blocked Account, @Betty_Moges, May Be Reported Intensionally by Some Groups. Please Unblock It. Cc: @jack @TwitterSupport @Twitter @TwitterSafety @TwitterAPI @TwitterEng @nickpickles @yoyoel @Policy @TwitterGov,” Twitter, February 8, 2021, https://twitter.com/iyoba4u/status/1358882600899723267; Iyoba 🇪🇹 🟩🟨🟥 🇪🇹(@iyoba4u), “@EthiopiaPrevai1 @UnityForEthio @Lion_King_ET @TwitterSupport @NeaminZeleke @HannaLoveNotWar @LanderMiddle No Suspicious Activities Were Made by This Blocked Account, @UnityForEthio, May Be Reported Intensionally by Some Groups. Please Unblock It. Cc: @jack @TwitterSupport @Twitter @TwitterSafety @TwitterAPI @TwitterEng @nickpickles @yoyoel @Policy @TwitterGov,” Twitter, February 8, 2021, https://twitter.com/iyoba4u/status/1358822939643289600.

- 10Email directly with authors.

- 11On this basis, Facebook removed 65 Facebook accounts, 52 pages, 27 groups, and 32 accounts for violating its policy. Nathaniel Gleicher, “Removing Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour from Ethiopia," About Facebook (blog), June 16, 2021, https://about.fb.com/news/2021/06/removing-coordinated-inauthentic-beha…; Nathaniel Gleicher, “Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior Explained,” About Facebook (blog), December 6, 2018, https://about.fb.com/news/2018/12/inside-feed-coordinated-inauthentic-b….

- 12On this basis, Facebook removed 65 Facebook accounts, 52 pages, 27 groups, and 32 instagram accounts for violating its policy. Nathaniel Gleicher, “Removing Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour from Ethiopia," About Facebook (blog), June 16, 2021, https://about.fb.com/news/2021/06/removing-coordinated-inauthentic-beha…; Nathaniel Gleicher, “Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior Explained,” About Facebook (blog), December 6, 2018, https://about.fb.com/news/2018/12/inside-feed-coordinated-inauthentic-b….

Stage 5: Adjustments by campaign operators

Once a significant volume of evidence made crimes committed by Ethiopian and allied forces harder to deny, the government committed to conducting its own investigations while continuing to promote its narrative about TPLF disinformation.1 At the same time, government supporters sought out and shared content that supported their beliefs that reports of atrocities and impending humanitarian crises were overblown or fabricated. These included op-eds, self-published , and reports of opaque origins.

Tigrayan campaign increasingly relying on international press and NGOs

When Tigrayan campaigners spread unconfirmed information about events on the ground, pro-government campaigners pointed to these instances as proof that Tigrayan activists were intentionally spreading disinformation. Relatively early on, many Tigrayan campaigners operators adjusted their strategy to avoid spreading false information.

“We quickly learned that sharing [unconfirmed information] was a mistake and that false information would be used to undermine our movement so we tried to not share anything unless it was reported by trustworthy sources, like international media,”2 said a Tigrayan campaign operator in Toronto.