Targeted Harassment: The Spread of #CoronaJihad

Overview:

In the spring of 2020, a viral slogan purporting that Muslims were purposely spreading COVID-19 in India was disseminated online using recontextualized videos. India’s ruling eventually adopted the term, allowing it to spread even further, leading to harassment before critical press and efforts by social media platforms dampened the campaign. Based on the evidence and pattern of activity, #coronajihad was likely not a campaign crafted and executed by a single set of operators, but rather one in which individuals participated organically, with influencers helping to spread the spread the slogan in the early stages.

STAGE 1: Manipulation Campaign Planning and Origins

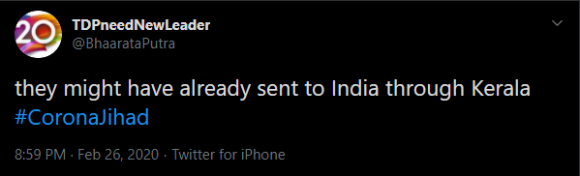

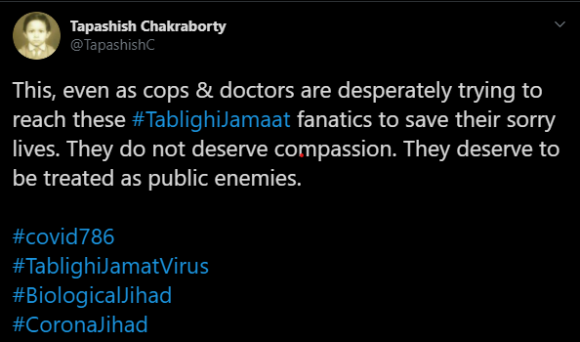

The hashtag #Coronajihad first appeared on Twitter on February 26, 2020, where it was used to speculate that Pakistan had sent COVID-19 to India.1 The phrase has generally been used pit two identity groups against each other, to convey the idea that Muslims are weaponizing the coronavirus to target Hindus.”2 The term’s emergence initially coincided with Tablighi Jamaat, a Muslim missionary movement that held its annual congregation in New Delhi in early March.3 Of the 4,400 cases of COVID-19 in India by April 7, around 30% were traced back to the gathering, and over 27,000 Tablighi Jamaat members and their contacts were quarantined in 15 states.4 Though “the available data does not support the speculation” that the blame for the coronavirus epidemic in India lies mainly with Tablighi Jamaat,5 the convening was branded across social media as a “superspreader” event and directly correlated with the simultaneous rise in Islamophobic rhetoric and hashtags such as #BanTheBook, #Quranovirus, #BiologicalJihad, #MuslimVirus, #MuslimDistancing, and #Jihadivirus.6 Though content blaming Muslims for the spread of coronavirus was first posted to Twitter by Indian Hindu nationalists, it was also amplified by global Islamophobic individuals and groups, many of whom were based in the West.7

- 1TDPneedNewLeader (@BhaarataPutra), “they might have already sent to India through Kerala #CoronaJihad,” , February 26, 2020, https://twitter.com/BhaarataPutra/status/1232847731938349056.

- 2Billy Perrigo, “Coronavirus Exacerbates Islamophobia in India,” Time, April 3, 2020, https://time.com/5815264/coronavirus-india-islamophobia-coronajihad/

- 3“Tablighi Jamaat: The Group Blamed for New Covid-19 Outbreak in India,” BBC, April 2, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-52131338.

- 4Akash Bisht and Sadiq Naqvi, “How Tablighi Jamaat Event Became India’s Worst Coronavirus Vector,” Al Jazeera, April 7, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/07/how-tablighi-jamaat-event-became-indias-worst-coronavirus-vector/.

- 5Hannah Ellis-Petersen and Shaikh Azizur Rahman, “Coronavirus Conspiracy Theories Targeting Muslims Spread in India,” The Guardian, April 13, 2020, sec. World news, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/13/coronavirus-conspiracy-theories-targeting-muslims-spread-in-india.

- 6“Coronajihad,” EQUALITY LABS, accessed October 5, 2020, https://www.equalitylabs.org/coronajihad.

- 7 Burhan Wazir, “Islamophobic , Hate Speech Swamps Social Media during Pandemic,” Rappler, May 22, 2020, https://r3.rappler.com/technology/features/261719-islamophobic-disinformation-hate-speech-social-media-coronavirus-pandemic-coda-story.

STAGE 2: Seeding Campaign Across Social Platforms and Web

Aided by targeted harassment and trolling methods, a cascade of recontextualized and decontextualized videos, , and posts began flooding social media networks in late March, falsely claiming to portray Muslim men trying to infect others with coronavirus.1 On March 28, a 2018 video that showed Muslims licking plates (with the true intention of promoting zero food waste) was shared on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. The text accompanying the video accused Muslims of trying to spread the virus in various places across the country.2 On April 1, a video of a Sufi tradition was shared on with a false claim that it showed Muslims at the Tablighi Jamaat congregation intentionally sneezing on each other to spread the virus.3 On April 2, an old video from February showing a person spitting on cops was rebranded as a video of a Muslim spitting to intentionally infect cops,4 leading to the common use of the hashtag #spittingjihad in addition to #coronajihad. And on April 3, a video from Thailand was shared with a title claiming that a Muslim man from the Delhi congregation was caught intentionally coughing on somebody; in reality, there was no evidence that the person had ever attended the Delhi congregation.5 Images blatantly comparing the Tablighi Jamaat (and Indian Muslims generally) to terrorists or venomous snakes became widespread on social media as well.6

From March 28 to April 3, 2020, the viral slogan #CoronaJihad spread rapidly on Twitter, appearing in almost 300,000 tweets potentially seen by 170 million users.7 On March 31, usage of the term peaked, appearing over 20,000 times that day on Twitter.8 According to a by Equality Labs, the conversations have since generated more than 700,000 points of engagement, including likes, clicks, shares and comments, and the majority of users creating and sharing such content are young men between the ages of 18 and 34, based in India or the US.9 In addition to Twitter, the term “coronajihad” was used on Facebook, receiving over 694,000 interactions on 6,643 posts between February 1 to September 23, 2020.

- 1Shweta Desai and Amarnath Amarasingam, “#CoronaJihad: COVID-19, Misinformation, and Anti-Muslim Violence in India,” ResearchGate, May 2020, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341651003_CoronaJihad_COVID-19_Misinformation_and_Anti-Muslim_Violence_in_India.

- 2The Quint, “Muslims Viral Video Fact Check | Old Video Shared as Muslim Men Licking Utensils to Spread COVID-19,” The Quint, April 3, 2020, https://www.thequint.com/news/webqoof/video-of-muslims-licking-plates-to-spread-covid-19-its-a-tradition-fact-check.

- 3Pooja Chaudhuri and Pratik Sinha, “Video of Sufi Ritual Falsely Viral as Mass Sneezing in Nizamuddin Mosque to Spread Coronavirus Infection,” Alt News (blog), April 1, 2020, https://www.altnews.in/video-of-sufi-ritual-falsely-viral-as-mass-sneezing-in-nizamuddin-mosque-to-spread-coronavirus-infection/.

- 4Pooja Chaudhuri, “Coronavirus: Video of an Undertrial in Mumbai Falsely Viral as Nizamuddin Markaz Attendee Spitting at Cop,” Alt News (blog), April 2, 2020, https://www.altnews.in/coronavirus-video-of-an-undertrial-in-mumbai-falsely-viral-as-nizamuddin-markaz-attendee-spitting-at-cop/.

- 5Rosy (@rose_k01), “CCTV Footage shows This MuIIаh INTENTIONALLY coughed on Mans face!! Then he goes around touching stuff. Such VILЕ minded people😡😡 Stay away from these Сrееру people #TJKMKB #TablighiJamatVirus #CoronaJihad #CoronavirusPandemic #COVID2019india,” Twitter, April 3, 2020, accessed via http://archive.is/A3Gq7.

- 6Desai and Amarasingam, , “#CoronaJihad: COVID-19, Misinformation, and Anti-Muslim Violence in India.”

- 7Burhan Wazir, “Exclusive: Islamophobic Disinformation and Hate Speech Has Swamped Social Media during the Coronavirus Pandemic,” Coda Story (blog), May 21, 2020, https://www.codastory.com/disinformation/exclusive-islamophobic-disinformation-and-hate-speech-has-swamped-social-media-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic/.

- 8Author’s own analysis based on Twint data from Jan 1, 2020 to May 22, 2020.

- 9Wazir, “Exclusive: Islamophobic Disinformation and Hate Speech Has Swamped Social Media during the Coronavirus Pandemic.”

STAGE 3: Responses by Industry, Activists, Politicians, and Journalists

An outcome of this campaign was that it muddied the waters about how COVID-19 was spread in India during the spring of 2020. It took place within the context of a rise in anti-Muslim hate crimes. Officials from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the current ruling political party of India, adopted and amplified the narrative linking coronavirus to Islamic terrorism. On April 1, party representatives singled out the Tablighi Jamaat gathering, accusing it of being the single largest source of the virus spread in India, calling it “coronaterrorism”1 and a “Talibani crime.”2 “Tablighi Jamaat people have started to spit on workers and doctors in quarantine centers,” tweeted BJP Delhi leader Kapil Mishra. “Clearly, their intention is to kill maximum people...they should be treated like terrorists.”3 On April 6, officials attributed the doubling rate of infection in India to the gathering. “If it were not for the congregation, India’s rate of doubling— that is in how many days the cases have doubled — would have been at 7.4 days [instead of 4.1 days],” said Lav Agarwal, the joint secretary of India’s Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.4

The BJP’s adoption of the “coronajihad” narrative generated a tremendous amount of media exposure, which resulted in the widespread use of “Coronajihad” by many mainstream news outlets. Domestic media coverage largely advanced the same narrative as the BJT. On April 2, news outlet ABP Live ran a segment about the mosque that serves as Tablighi Jamaat headquarters, entitled “How Nizamuddin Markaz turned into corona bomb.”5 TV9 Bharatvarsh, a free-to-air TV news channel, broadcast an “investigative report” claiming that several Rohingya refugees were deliberately infected with COVID-19 at the Tablighi Jamaat congregation in March and then sent out to different parts of India to spread the infection on a large scale.6 On April 7, Amish Devgan, the managing editor of News18 India, claimed on his show Aar Paar to have “concrete information” that Pakistan was directly responsible for the coronavirus pandemic in India; this was later debunked by the news website NewsLaundry.7 Islamophobic articles from Indian outlets such as PGurus were published; one appeared on April 8 with the headline “How to deal with Novel Corona Jihad – Time for National crackdown.”8

This exploitation of this deeply held prejudice against Muslims during the active crisis of the COVID-19 outbreak led to mob violence against Muslims, resulting in 53 deaths and over 200 injuries.9

- 1admin, “‘This Is Corona Terrorism’, Says BJP’s Sangeet Som over Nizamuddin Markaz,” ABP Live, April 1, 2020, https://news.abplive.com/videos/news/india-this-is-corona-terrorism-says-bjps-sangeet-som-over-nizamuddin-markaz-1186833.

- 2ThePrint, This Is a “Talibani Crime” by Tablighi Jamaat: Naqvi on Nizamuddin Markaz Gathering, , 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4HxAg_zh0ag.

- 3Kapil Mishra (@KapilMishra_IND), “तबलीगी जमात के लोगों ने अब क्वारंटाइन केंद्रों के कर्मचारी और डॉक्टरों पर थूकना शुरु कर दिया स्पष्ट हैं, इनका इरादा ज्यादा से ज्यादा लोगों को कोरोना करना और उन्हें मारना है ये आतंकवादी हैं और इनका आतंकवादियों जैसा इलाज ही करना पड़ेगा They should be treated like Terrorists,” Twitter, April 1, 2020, https://twitter.com/KapilMishra_IND/status/1245359875598594051.

- 4Rhythma Kaul, “Covid-19 Cases Doubling in 4.1 Days, Jamaat Incident Worsened Coronavirus Spread: Govt,” Hindustan Times, April 5, 2020, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/covid-19-doubling-rate-in-india-at-4-1-days-govt/story-CcMgi8sSrZ7LnBp1oZ70OL.html.

- 5admin, “How Nizamuddin Markaz Turned into Corona Bomb,” ABP Live, April 2, 2020, https://news.abplive.com/videos/news/india-how-nizamuddin-markaz-turned-into-corona-bomb-master-stroke-1188020.

- 6Tapan Kumar Bose, “COVID-19: Rohingya Refugees in India Are Battling Islamophobia and Starvation,” The Wire, May 1, 2020, https://thewire.in/rights/india-rohingya-refugees-starvation-covid-19.

- 7Ayan Sharma and Chahak Gupta, “Audit of Bigotry: How Indian Media Vilified Tablighi Jamaat over Coronavirus Outbreak,” Newslaundry, April 27, 2020, https://www.newslaundry.com/2020/04/27/audit-of-bigotry-how-indian-media-vilified-tablighi-jamaat-over-coronavirus-outbreak.

- 8 Venkat Sudheendra, “How to Deal with Novel Corona Jihad - Time for National Crackdown,” PGurus (blog), April 8, 2020, https://www.pgurus.com/how-to-deal-with-novel-corona-jihad-time-for-national-crackdown/.

- 9Wazir, “Islamophobic Disinformation, Hate Speech Swamps Social Media during Pandemic.”

STAGE 4: Mitigation

International press coverage was largely critical. Foreign outlets reported widely on the use of #coronajihad online and seemed to condemn India and the BJP for its Islamophobia. Between March 31 and May 22, there were 150 stories in leading global English news sources discussing India’s Islamophobia and use of terms like “coronajihad,”1 featuring headlines such as “Islamophobia taints India’s response to the coronavirus” (The Washington Post),2 “Coronavirus conspiracy theories targeting Muslims spread in India” (The Guardian),3 and “Would-be-autocrats are using covid-19 as an excuse to grab more power” (The Economist).4

Politicians and NGOs around the world quickly criticized the anti-Muslim hysteria in India and urged the government to take action. On April 2, Sam Brownback, the US ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom, said it was “wrong by governments to do this” and urged them to “put this down and state very clearly that this is not the source of the coronavirus. It’s not the religious minority communities. And they should go out there in open messaging and say no, this is not what happened.”5 On April 6, the World Health Organization stated, “It is very important that we do not profile the cases on the basis of racial, religious and ethnic lines.” On April 7, over 50 international organizations sent a letter titled, “Stop the rapid spread of COVID-19 Islamophobic hate speech and disinformation” to Narenda Modi, Mark Zuckerberg, Jack Dorsey, and WHO Head Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.6 The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), the Kuwait government, a royal princess of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and a number of Arab activists issued public denunciations as well.7 On April 8, 109 members of civil society responded, releaseing a statement “condemning the communalization of COVID-19 spread in India” and explicitly referencing the Islamophobic coverage by the mainstream media and attempts to brand Muslims as the “superspreaders.”8

On April 19, India Prime Minister Narendra Modi attempted to minimize Islamophobia by urging solidarity, tweeting, “COVID-19 does not see race, religion, colour, caste, creed, language or borders before striking. Our response and conduct thereafter should attach primacy to unity and brotherhood. We are in this together.”9 Mohan Bhagwat, the leader of BJP’s ideological group, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, stated that communities couldn’t be blamed for “the mistakes of few individuals,” an apparent reference to the Tablighi Jamaat celebration.10

On June 22, the Telangana High Court issued a notice to Twitter to remove trending hashtags that were linking COVID-19 to Islam, including #coronajihad.11 On April 15, despite the popularity of the hashtag, its use on Twitter fell sharply overnight, from over 200 occurrences daily occurrences to only one.12 In August a Twitter representative reportedly told the court that the company had removed the content.13 As of September 22, 2020, a search on Twitter shows 21 results, most of which are critical of the hashtag and Islamophobia in India. However, some inflammatory and islamophobic tweets containing #coronajihad are still available, though they have been de-indexed from Twitter search results.14

Facebook made no announcements about . Users of the platform are still able to search for “coronajihad,” which yields results including content containing the hashtag “#coronajihad.” However, when users search for the hashtag “#coronajihad” itself, the platform returns zero results, indicating the hashtag has been de-indexed. Notably, when searching for “#coronajihad” Facebook briefly displays the text “13K people are posting about this," before changing to “We Didn't Find Anything / Make sure everything is spelled correctly, or try searching for a different hashtag.”15

- 1Media Cloud, search term: "coronajihad;" dates searched: March 20 - May 23, 2020, 2020; sources searched: global English-language sources; https://explorer.mediacloud.org/#/queries/search?qs=%5B%7B%22label%22%3A%22coronajihad%22%2C%22q%22%3A%22coronajihad%22%2C%22color%22%3A%22%231f77b4%22%2C%22startDate%22%3A%222020-03-20%22%2C%22endDate%22%3A%222020-05-23%22%2C%22sources%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B9272347%5D%2C%22searches%22%3A%5B%5D%7D%5D.

- 2 Rana Ayyub, “Islamophobia Taints India’s Response to the Coronavirus,” Washington Post, April 6, 2020, http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/04/06/islamophobia-taints-indias-response-coronavirus/.

- 3Hannah Ellis-Petersen and Shaikh Azizur Rahman, “Coronavirus Conspiracy Theories Targeting Muslims Spread in India,” The Guardian, April 13, 2020, sec. World news, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/13/coronavirus-conspiracy-theories-targeting-muslims-spread-in-india.

- 4“Would-Be Autocrats Are Using Covid-19 as an Excuse to Grab More Power,” The Economist, April 23, 2020, http://www.economist.com/international/2020/04/23/would-be-autocrats-are-using-covid-19-as-an-excuse-to-grab-more-power.

- 5Samuel Brownback, “Briefing With Ambassador at Large for International Religious Freedom Sam Brownback On COVID-19 Impact on Religious Minorities (April 2),” U.S. Embassy in Georgia, April 2, 2020, https://ge.usembassy.gov/briefing-with-ambassador-at-large-for-international-religious-freedom-sam-brownback-on-covid-19-impact-on-religious-minorities-april-2/.

- 6Equality Labs, “#StopCOVIDIslamophobia: COVID-19 Appeal Letter,” Medium, April 9, 2020, https://medium.com/@EqualityLabs/stopcovidislamophobia-covid-19-appeal-letter-c47dd0860ff1.

- 7Bilal Kuchay, “Why Arabs Are Speaking out against Islamophobia in India,” Al Jazeera, April 30, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/30/why-arabs-are-speaking-out-against-islamophobia-in-india/.

- 8The Wire Staff, “‘Finding a Scapegoat’: 109 Citizens Urge Govt, Media to Stop Communalising COVID-19,” The Wire, April 8, 2020, https://thewire.in/communalism/coronavirus-tablighi-jamaat-scapegoat-muslims.

- 9PMO India (@PMOIndia), “COVID-19 does not see race, religion, colour, caste, creed, language or borders before striking. Our response and conduct thereafter should attach primacy to unity and brotherhood. We are in this together: PM @narendramodi,” Twitter, April 19, 2020, https://twitter.com/PMOIndia/status/1251839308085915649.

- 10Kuchay, “Why Arabs Are Speaking out against Islamophobia in India.”

- 11“File Counter on Tweets Linking COVID-19 Spread to Islam: Telangana High Court to Twitter,” The New Indian Express, July 25, 2020, https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/telangana/2020/jul/25/file-counter-on-tweets-linking-covid-19-spread-to-islam-telangana-high-court-to-twitter-2174506.html.

- 12Frequency of use of #Coronajihad (or #Coronajihaad) on Twitter (Source: Author’s own analysis based on data collected through Twint from Jan 1, 2020 to May 22, 2020).

- 13TNN, “Islamophobic Hashtags Removed: Twitter,” The Times of India, August 21, 2020, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/hyderabad/twitter-islamophobic-hashtags-removed/articleshow/77664044.cms.

- 14Gautam Banerjee (@gbanerjee10), “They all need to be put into gas chamber...!! With every passing day...thet are becoming increasingly difficult to be handled with...those jihadi kathmollahs, seems to have only one motto, make entire India ill...!! #CoronaJihad,” Twitter, March 20, 2020, https://twitter.com/gbanerjee10/status/1241037698468417541; Caralisa Monteiro (@runcaralisarun), “These #Jamaatis causing #CoronaJihad.,” Twitter, May 13, 2020, https://twitter.com/runcaralisarun/status/1260483737495707652.

- 15The HTML source for the search results includes the text “13K people are posting about this." It is unclear what triggers the search results and display text to change.

STAGE 5: Adjustments by Manipulators to New Environment

Though appeals to inclusivity along with content removal and have shown to be effective in containing “Coronajihad,” individuals have adjusted to find ways to promote the term at a limited scale through other channels. For example, on May 8, an unofficial definition for “Coronajihad” was added to Urban Dictionary, which remains online.1 Videos using the term in an Islamophobic context are also available on YouTube at time of writing. Elsewhere, allegations of censorship and “whitewashing” can be found on and smaller outlets.2 Furthermore, because of Facebook and Twitter’s selective response to the term, coronajihad and #coronajihad are still available on the platforms.

- 1“Urban Dictionary: Coronajihad,” Urban Dictionary, May 8, 2020, https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=coronajihad.

- 2“R/IndiaSpeaks - Wikipedia Is Trying to Whitewash Corona-Jihad of a Jihadi Sympathizer Group Who Helped al-Qaeda for the 9/11 Attack.,” reddit, April 17, 2020, https://www.reddit.com/r/IndiaSpeaks/comments/g3c0c5/wikipedia_is_trying_to_whitewash_coronajihad_of_a/.

Cite this case study

Sanjana Rajgarhia, "Targeted Harassment: The Spread of #CoronaJihad," The Media Manipulation Case Book, July 7, 2021, https://casebook-static.pages.dev/case-studies/targeted-harassment-spread-coronajihad.