#WeAreAllSeditious: Malaysian Activists and the Meme War Against Corruption

Overview

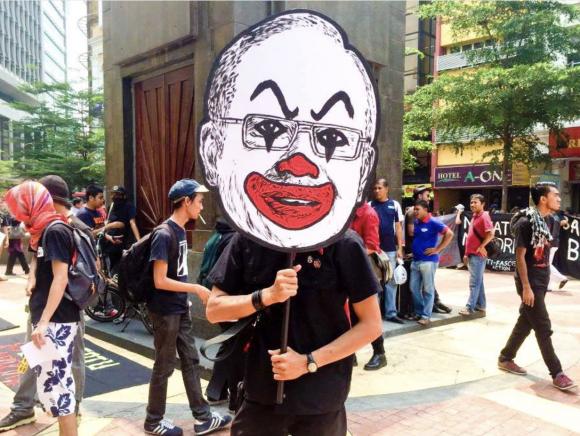

In early 2016, Malaysians and the international community became increasingly aware of the 1MDB corruption scandal, especially its links to the Malaysian government and then Prime Minister Najib Razak.1 As that awareness grew, artist and activist Fahmi Reza posted an image satirizing Najib and the country’s widespread corruption. It also criticized the colonial-era Sedition Act, which had been used multiple times in the previous years to censor and intimidate political opponents, dissidents, and activists in the country. The image and its subsequent reinterpretations were shared widely on social media, received press coverage both domestically and internationally, and was printed on t-shirts, stickers, buildings, and sign posts across the country. Although the government arrested, charged, and convicted Fahmi in a bid to contain its proliferation, the meme nonetheless continued to gain traction, becoming a symbol of resistance that is still used to this day.

- 1The 1MDB financial scandal is one of the world’s largest financial frauds with over US$4.5 billion in stolen funds, sparking multiple investigations by law enforcement agencies across the globe, including the United States, Singapore, Australia, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Switzerland, the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom. The scandal was largely broken by journalists and independent like The Edge Reports, Malaysiakini, and Sarawak Report, who risked their privacy and safety in doing so. Recommended reading: Billion Dollar Whale: The Man Who Fooled Wall Street, Hollywood, and the World by Bradley Hope and Tom Wright; The Sarawak Report: The Inside Story of the 1MDB Expose by Clare Rewcastle Brown; Heather Chen, Kevin Ponniah, and Mayuri Mei Lin, “1MDB: The Playboys, PMs and Partygoers around a Global Financial Scandal,” BBC News, August 9, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-46341603.

STAGE 1: Manipulation Campaign Planning and Origins

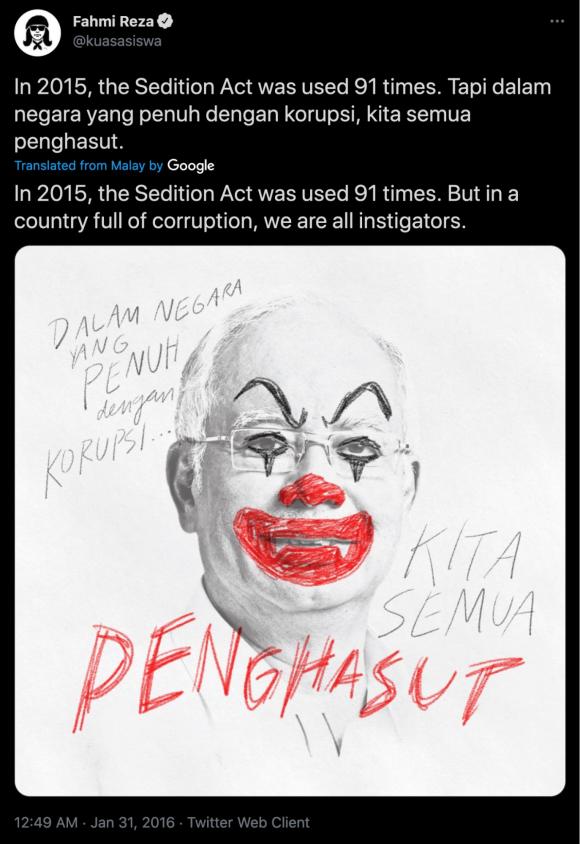

On January 31, 2016, graphic artist and activist Fahmi Reza posted a hand-drawn image of and then Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak as a clown (figure 1 below) on his personal Twitter and Facebook accounts.1 The accompanying text read, “In 2015, the Sedition Act was used 91 times. Tapi dalam negara yang penuh dengan korupsi, kita semua penghasut. [Translation: But in a country full of corruption, we are all agitators].”

The tweet and its underlying message immediately struck a chord with Malaysians angry at the country’s widespread corruption and garnered hundreds of retweets and likes within a few hours. The Prime Minister at the time was, and still is, embroiled in a billion-dollar financial scandal linked to a government investment company known as 1MDB. In 2015, the year prior, a report by the Wall Street Journal alleged that nearly $700 million from 1MDB had been channeled into Najib’s personal bank accounts.2 In response, Najib not only denied the allegations but also fired his then-deputy Muhyiddin Yassin and removed the attorney general responsible for investigating him.

In an interview a year later, Fahmi further explains that he initially posted the image as a reaction to two issues:

“First, to the news that the Malaysian attorney general cleared Najib of any corruption relating to the long-running financial scandal, absolving him from all wrongdoing. The level of absurdity that the government used to cover up the scandal and corruption is astounding. Second, it was a reaction to an Amnesty International report, which states that in 2015 alone there were 91 instances of the Sedition Act being used by the government to arrest, investigate, or charge individuals. In Malaysia, the government is very intolerant of dissent.”3

During this time, the Sarawak Report, a whistleblowing media outlet, was blocked, while two more newspapers were suspended over their reporting on the scandal.4 And as Fahmi mentions in his interview, the new Attorney General, Apandi Alli, had cleared Najib of any wrongdoing, claiming that the money in his bank accounts were a donation from the Saudi Arabian royal family.5 As tensions rose, thousands had already taken to the streets to protest and demand Najib’s resignation, turning the financial scandal into a political wedge issue that pit supporters of Najib and his coalition, Barisan Nasional (BN), against opposition politicians and much of .6 However, activists and opponents of Najib were not the only ones who took notice of Fahmi’s tweet.

- 1Fahmi Reza, “In 2015, the ruler of our country has used the Sedition Act 91 times as a weapon to arrest, investigate and indict the citizens of our country who dare to wake up speechless. They are labeled as agitators by the rulers. But in a country full of corruption, we are all instigators. Solidarity for all victims of the Sedition Act. #MansuhAktaHasutan,” , January 30, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/login/?next=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2Fkuasasiswa%2Fposts%2F953346978034070; Fahmi (@kuasasiswa) Reza, “In 2015, the Sedition Act was used 91 times. Tapi dalam negara yang penuh dengan korupsi, kita semua penghasut.,” , January 30, 2016, https://twitter.com/kuasasiswa/status/693672449058041856.

- 2WSJ com News Graphics, “Malaysia’s 1MDB Decoded: How Millions Went Missing,” The Wall Street Journal, November 22, 2015, http://graphics.wsj.com/1mdb-decoded.

- 3Roger Peet, “Fahmi Reza: We Are All Seditious,” Just Seeds, March 1, 2017, https://justseeds.org/fahmi-reza-we-are-all-seditious/.

- 4Beh Lih Yi, “Sarawak Report Whistleblowing Website Blocked by Malaysia after PM Allegations,” The Guardian, July 20, 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jul/20/sarawak-report-whistleblowing-website-blocked-by-malaysia-over-pm-allegations; Austin Ramzy, “Malaysia Suspends 2 Newspapers Covering Scandal at State-Owned Fund,” The New York Times, July 24, 2015, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/25/world/asia/malaysia-suspends-2-newspapers-covering-scandal-at-state-owned-fund.html.

- 5“Malaysian PM Cleared of Wrongdoing over $681m Donation,” Al Jazeera, January 26, 2016, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/1/26/malaysian-pm-cleared-of-wrongdoing-over-681m-donation.

- 6“Malaysia Protests against PM Najib Razak Draw Thousands,” BBC News, August 30, 2015, sec. Asia, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-34093338.

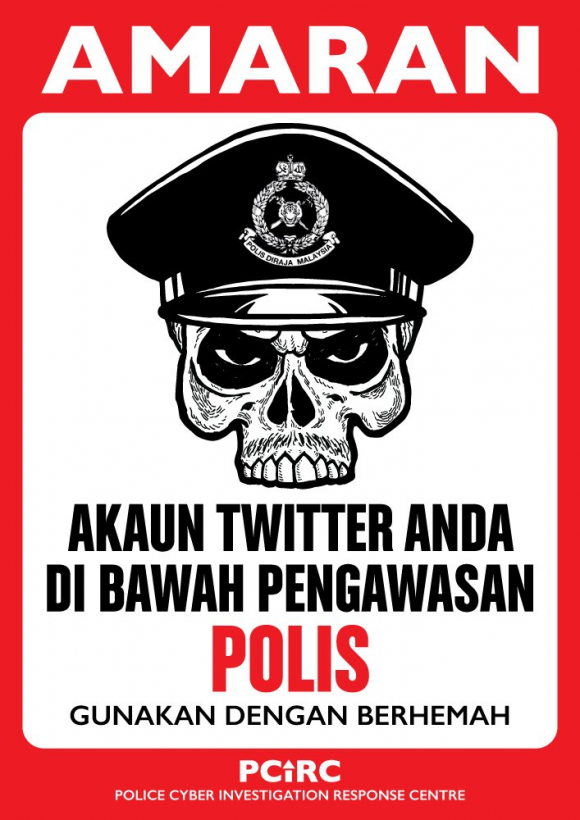

Approximately three hours after the initial tweet went up, the official Twitter account of the Malaysian Police Cyber Investigation Response Centre tweeted at Fahmi warning him that he was under surveillance due to his tweet and to watch what he posts from then on.1 Fahmi, in response, trolled the police by tweeting an image (figure 2 below) with the hashtag #BigBrotherIsWatchingYou, accompanied with the text, “WARNING! Your twitter account is under police surveillance. Use prudently.”2 He also posted to his Facebook page, “In a country that uses laws to protect the corrupt and oppress those brave enough to speak out, it is time that we stop being prudent when fighting against corrupt rulers."3 Had the authorities left Fahmi alone and ignored the initial post, the meme may have proliferated primarily within like-minded groups. However, by publicly warning Fahmi that his post was inappropriate and that his account would be subject to surveillance, the police escalated an otherwise irreverent social media post into a meme war.

- 1PCIRC OFFICIAL (@OfficialPcirc), “AccTwitter @kuasasiswa, acc anda dibwh pengawasan PDRM.Gunakan dgn berhemah&berlandaskan undang2.@KBAB51 @PDRMsia https://t.co/2SJ5ABEYkc,” Twitter, January 31, 2016, https://twitter.com/OfficialPcirc/status/693714261537763334; PCIRC OFFICIAL (@Officialpcirc), “AccTwitter @kuasasiswa, acc anda dibwh pengawasan PDRM.Gunakan dgn Berhemah&berlandaskan Undang2.@KBAB51 @PDRMsia,” Twitter accessed via archive.is, April 30, 2021, http://archive.is/pb3Mz.

- 2Fahmi (@kuasasiswa) Reza, “AMARAN! Akaun twitter anda di bawah pengawasan polis. Gunakan dengan berhemah. #BigBrotherIsWatchingYou https://t.co/vTRzobgqlJ,” Twitter, February 2, 2016, https://twitter.com/kuasasiswa/status/694338154417909760.

- 3Maddison Connaughton, “Meet the Malaysian Artist Fighting Government Corruption with a Cartoon,” Vice, April 4, 2016, https://www.vice.com/en/article/wdjy9n/meet-the-artist-facing-off-against-malaysias-corrupt-prime-minister.

STAGE 2: Seeding Campaign Across Social Platforms and Web

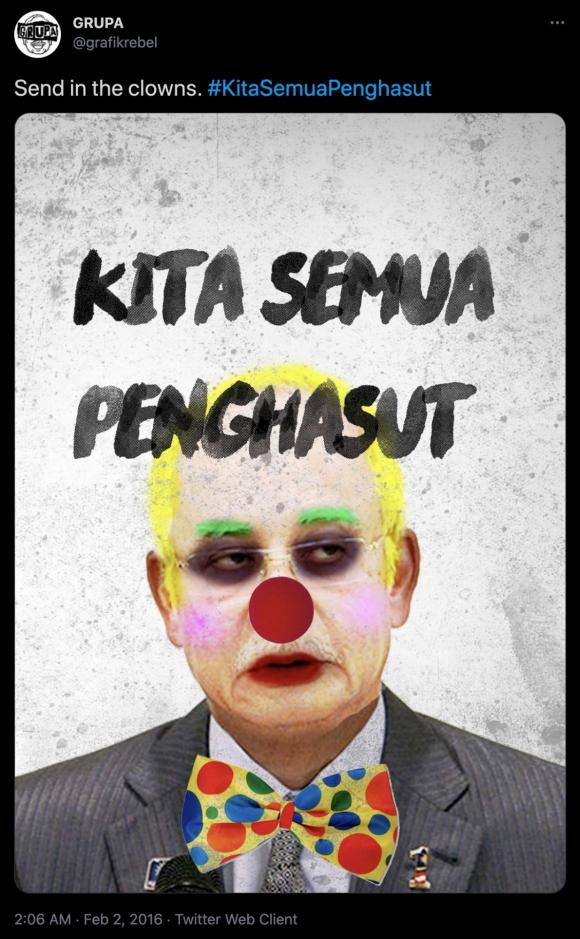

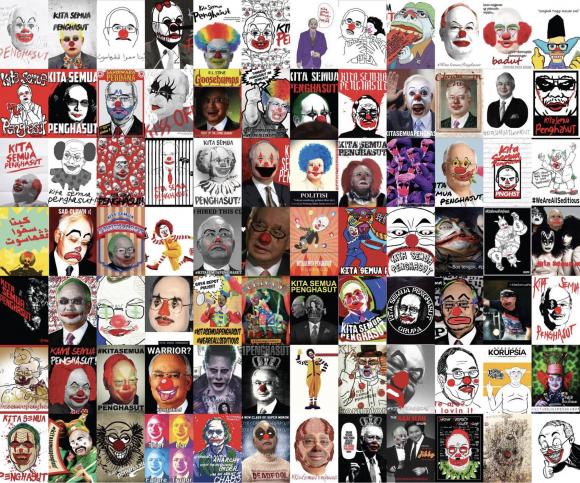

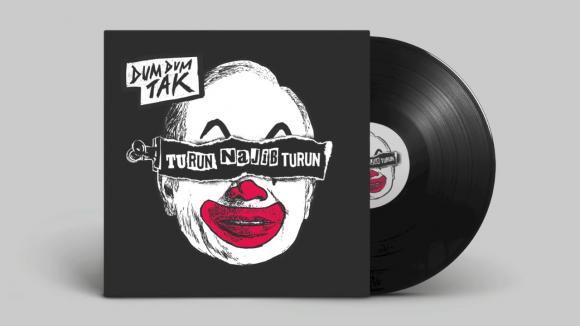

The perceived overreaction by the Malaysian Police Cyber Investigation Response Centre, sparked a response from other artists, activists, and partisan netizens, turning them into campaign participants. The police’s warning, far from deterring Fahmi and others from using the image, instead resulted in the image’s further distributed amplification and continual remixing. An art collective, Grafik Rebel Untuk Protes & Aktivisme (GRUPA), uploaded their own versions to Twitter and Facebook (figures 3 and 4 below),1 while punk band Dum Dum Tak uploaded a song to YouTube titled “Turun Najib Turun (Down Najib Down)” with the clown-faced Najib as the cover image (figure 5 below).2 In just a few days, the meme had spiraled into a grassroots campaign by activists and netizens alike and as the image gained steam, so did its accompanying viral slogan and hashtag, #KitaSemuaPenghasut (#WeAreAllSeditious).3

- 1GRUPA (@grafikrebel), “Send in the clowns. #KitaSemuaPenghasut,” Twitter, February 1, 2016, https://twitter.com/grafikrebel/status/694416555363336192; GRUPA. “Clowns... Clowns everywhere! 😳.” Facebook, February 16, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/grafikrebel/photos/a.877382295673878.1073741829.877323692346405/958147087597398/.

- 2Fahmi Reza, Dum Dum Tak - Turun Najib Turun - , 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WULrnUtpxz8.

- 3“We Are All Seditious, Graphic Artists Fight Back on Social Media,” The Edge Markets, February 5, 2016, http://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/we-are-all-seditious-graphic-artists-fight-back-social-media.

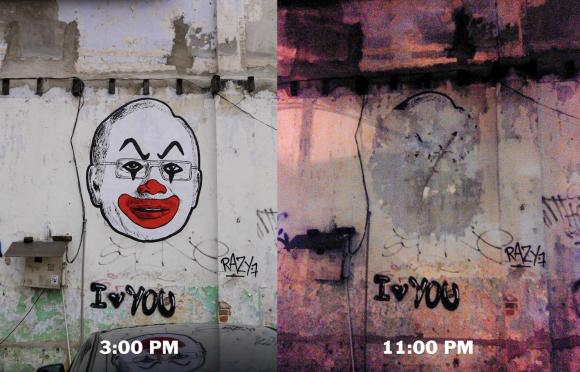

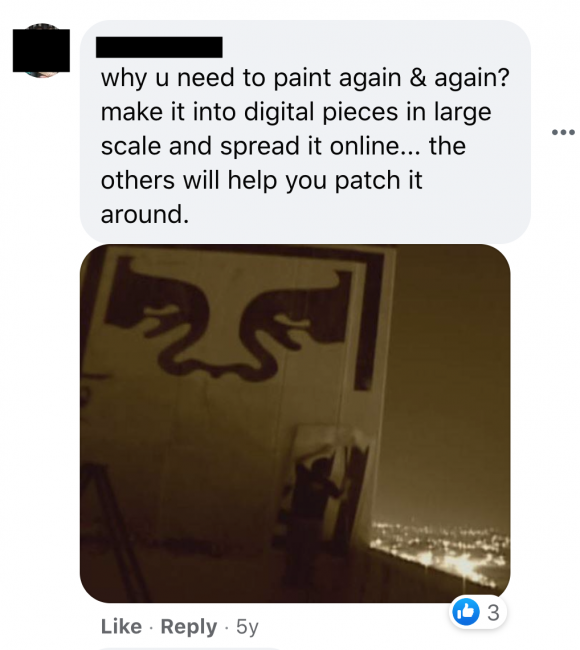

Fahmi, who saw his art as a “weapon”1 against a corrupt government, continued reiterating on the image, creating subsequent and imagery that were then posted on Facebook and Twitter,2 urging others to photoshop the image onto other images,3 as well as creating large-scale posters that were plastered across Kuala Lumpur.4 This shift from online to offline marked an escalatory move by Fahmi. Not only did he post images and updates in the lead-up to the actual poster, teasing his followers about what he was doing, he also commented on its subsequent removal. The first time he posted an image on the side of a building, it was removed just eight hours later (figure 6 below).

- 1“Malaysian Punk Artist Fahmi Reza Clowns with Scandal-Hit PM Najib,” The Straits Times, March 28, 2016, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/malaysian-punk-artist-fahmi-reza-clowns-with-scandal-hit-pm-najib.

- 2Fahmi Reza, “Dear Najib, you’re next. #KitaSemuaPenghasut,” Facebook, February 26, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=966796233355811.

- 3Fahmi Reza, “Kepada geng Penghasut yang pandai guna Photoshop, masa untuk kamu gunakan skill kamu untuk negara tercinta.,” Facebook, March 10, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=973242339377867.

- 4Fahmi Reza, “Apakah peranan pekerja seni dalam masyarakat? Bolehkah seni jadi senjata untuk melawan korupsi penguasa? #SeniSebagaiSenjata #KitaSemuaPenghasut,” Facebook, March 5, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=971193459582755.

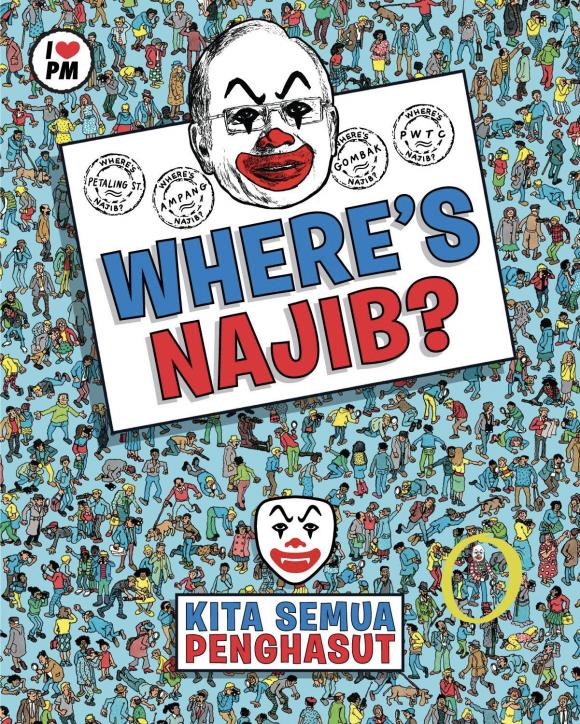

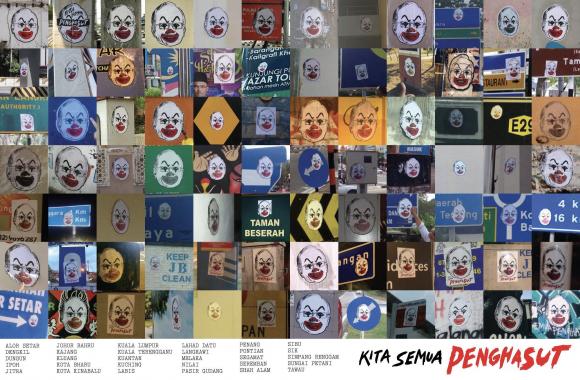

However, its removal—like the warning from the Malaysian police — only garnered more attention and copycats. Fahmi continued making and plastering the large images across Kuala Lumpur, inviting his followers to play “Where’s Najib?” and to try and find them throughout the city (figure 7 below). Others followed suit and plastered the image all throughout Malaysia on sign boards and buildings (figures 8 and 9 below).1 In an interview, Fahmi estimates around 80 were put up across Malaysia within a month.2 In addition to the posters, stickers and t-shirts were produced with all proceeds going to local NGOs.3 Fahmi approximates some 2,400 t-shirts were sold within weeks, whose buyers would then post photos of themselves wearing it on social media along with the hashtag #KitaSemuaPenghasut (figure 10 below).4

- 1Fahmi Reza, “The rebellion Is now spreading to Penang.,” Facebook, March 19, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=979286618773439; Fahmi Reza, “The rebellion Is now spreading to Johor!,” Facebook, March 28, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=987349831300451; Roger Peet, “Fahmi Reza: We Are All Seditious,” Just Seeds, March 1, 2017, https://justseeds.org/fahmi-reza-we-are-all-seditious/.

- 2 Roger Peet, “Fahmi Reza: We Are All Seditious.”

- 3Fahmi Reza, “SENARAI PENCETAK & PENJUAL T-SHIRT KITA SEMUA PENGHASUT,” Facebook, February 21, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/login/?next=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2Fkuasasiswa%2Fposts%2F964455536923214%3Ffbclid%3DIwAR0j-Knb6Qs8KwcR-tKVrk7kRhAA3BB0ttzOQ9K2jmKmHCgPU_7gjulDhws; “‘Clown-Faced Najib’ Will Now Raise Funds for Activism,” Malaysiakini, February 15, 2016, https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/330467.

- 4Maddison Connaughton, “Meet the Malaysian Artist Fighting Government Corruption with a Cartoon,” Vice, April 4, 2016, https://www.vice.com/en/article/wdjy9n/meet-the-artist-facing-off-against-malaysias-corrupt-prime-minister.

STAGE 3: Responses by Industry, Activists, Politicians, and Journalists

As the seeding and spreading of the meme and its multiple iterations continued on- and offline, mainstream international and local press took notice. Internationally, the story of Fahmi Reza, the meme, and the government’s response was covered in Australia,1 U.K.,2 France,3 Singapore,4 and the United States. Locally, it was covered by Bernama,5 the state’s press agency, as well as the Malay Mail,6 Malaysiakini,7 Says.com,8 and other local tabloids and news outlets. The meme and its subsequent reposting online and offline led many commentators to refer to the image as going “viral.”9

On March 29, 2016, Fahmi’s Twitter handle hit trending status in Malaysia.10 Two weeks later, he was interviewed by Vice, where he stressed, “...I will continue to fight against this authoritarian and corrupt regime using my art as my weapon. They can jail a rebel, but they can't jail the rebellion.”11 Aware of the attention he and the image were receiving, Fahmi frequently re-posted and commented on the press coverage he received on his own social media accounts.12

Outside of media exposure, politicians from both the ruling coalition and the opposition responded. On February 1, pro-Barisan Nasional (Najib’s coalition) leader Mohd Ali Baharom lodged a police report against Fahmi, stating that “[Fahmi’s] actions are an insult to the prime minister, cause public outrage and could influence the rakyat to hate the prime minister.”13 Meanwhile, Nurul Izzah Anwar, the vice president of the opposition People's Justice Party and daughter of Anwar Ibrahim, Najib’s political rival and former deputy prime minister of Malaysia, had uploaded the meme to her Instagram account. For this, the police also opened an investigation in which Nurul Izzah was questioned for an hour under Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 and Section 504 of the Penal Code.14

In addition to local activists supporting Fahmi and participating in the spread of the image, civil society organisations responded to the meme. Locally, Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM), a human rights organization, issued a statement condemning the government’s treatment of Fahmi, arguing that such tactics by the police “directly and indirectly prevent positive discourse on matters relating to national interest and jeopardize the democratic space and freedom of expression of all Malaysians.”15 The Electronic Frontier Foundation called out the Malaysian government’s ongoing use of censorship and network interference, citing Fahmi’s case as an example.16 Global Voices, an international network of anti-censorship bloggers and activists, also covered the meme and resulting state response.17

- 1“State of Fear,” Australian Broadcasting Company, obtained via Factiva transcripts, March 28, 2016.

- 2“PM Left Red Nosed by Censorship Protest,” BBC News, February 3, 2016, sec. Trending, https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-35486530.

- 3“Malaisie: un artiste caricaturant le Premier ministre en clown enflamme la Toile,” Le Point, March 28, 2016, https://www.lepoint.fr/monde/malaisie-un-artiste-caricaturant-le-premier-ministre-en-clown-enflamme-la-toile-28-03-2016-2028382_24.php.

- 4“Malaysian Punk Artist Fahmi Reza Clowns with Scandal-Hit PM Najib,” The Straits Times, March 28, 2016, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/malaysian-punk-artist-fahmi-reza-clowns-with-scandal-hit-pm-najib.

- 5“Police Investigate Nurul Izzah over Photo Insulting Najib,” Bernama Daily Malaysian News, March 7, 2016, https://www.astroawani.com/berita-malaysia/police-investigate-nurul-izzah-over-photo-insulting-najib-97765.

- 6A. Ruban, “Nurul Izzah under Police Probe for Reposting Activist’s Clown Face Sketch,” Malay Mail, March 7, 2016, https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2016/03/07/nurul-izzah-under-police-probe-for-reposting-activists-clown-face-sketch/1074903.

- 7“More Images of ‘clown-Faced’ Najib Emerge Online,” Malaysiakini, February 1, 2016, https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/329042.

- 8Nandini Balakrishnan, “Why The Man Who Drew Najib As A Clown Just Won’t Quit,” SAYS, June 23, 2016, https://says.com/my/lifestyle/why-the-man-fahmi-reza-who-drew-najib-as-a-clown-just-won-t-quit.

- 9“Malaysian Artist Jailed for Clown Caricature of PM Najib Razak,” South China Morning Post, February 20, 2018, https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/2133990/malaysian-artist-jailed-clown-face-caricature-pm-najib; David Leveille and Kierran Petersen, “Malaysian Street Artist Makes a Clown of Prime Minister,” The World from PRX, March 30, 2016, https://www.pri.org/stories/2016-03-30/malaysian-street-artist-makes-clown-prime-minister.

- 10Fahmi Reza, “Mampos! #KitaSemuaPenghasut,” Facebook, March 28, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=987412734627494.

- 11Maddison Connaughton, “Meet the Malaysian Artist Fighting Government Corruption with a Cartoon,” Vice, April 4, 2016, https://www.vice.com/en/article/wdjy9n/meet-the-artist-facing-off-against-malaysias-corrupt-prime-minister.

- 12Fahmi Reza, “Kenapa SAYS.COM tukar tajuk headline berita mereka tentang kempen sticker Penghasut?,” Facebook, March 19, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=979243555444412; Fahmi Reza, “Recently I was interviewed by a Malaysiakini journalist that asked me to share about my background and my journey from being a teenage punk rocker to a rebel graphic designer and visual activist.,” Facebook, March 20, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=979474158754685; Fahmi Reza, “Suratkhabar Berita Harian (Singapura),” Facebook, March 28, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=987228657979235; Fahmi Reza, “Suratkhabar Harian Kompas (Indonesia),” Facebook, March 28, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=987270874641680.

- 13“Ali Tinju Lodges Report over ‘Najib Clown Face’ Sketch,” Malaysiakini, February 1, 2016, https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/328989.

- 14Faisal Asyraf, “Police Record Nurul Izzah’s Statement over Post | New Straits Times,” NST Online, March 7, 2016, https://www.nst.com.my/news/2016/03/131519/police-record-nurul-izzahs-statement-over-instagram-post.

- 15Sevan Doraisamy, “Government of Malaysia Must Stop Threatening Freedom of Expression and Information,” Suaram, February 11, 2016, https://www.suaram.net/2016/02/11/government-of-malaysia-must-stop-threatening-freedom-of-expression-and-information/?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=70d920616200ae1fc73c35d8daef82d34fa878df-1621546153-0-AaMup_EyoSM_Ax6fSb2fP2lLJJWPm495OgL4A6U9dLAPvBGVY1buC-_XVeirS6kNKcywTrPHuaOwxVOC0mT_pJOUY1FIW2kkfSXQ4xSXF7JWh2C1t1UE_HvxP94OWhEUwR27cm8qRNGNZFSjDfWhY6bqDX_ilRqPP1KkeNQID6RISeyDafW73MlQmQK3YQwBkXpi0_KJkQB_F247xi_6o4X25iHQEbF4SKxfAKdoa23Kb4olSm9DZ_MyQQSWhyfE895C5ykKe6_0cazp9HYesJTB_8vJj6cKoezmlFn397cXK0jCUiR1QhVgXyIn4rU-b2BjWQChKO6Slh9PLLODLFI6YIvd9UB-wJqx_N6WIOGU-myzKMSxh0Nz8t6fkRFN_5zxnBTCB8xAeZPsznKzbhkKmc1ZlDWB1Gdw-j9OgAOj0bwZf0HuFBwRoviSlUJGr2Ibb8olu5d7PdvJQMmrfVoBU2w3U0UO0NTWTL9HkhLx450BaQQ-Mqd8lhBF6so9e-DHtSyuHA6ccjzCWMm-ia8.

- 16Jeremy Malcolm, “Malaysian Internet Censorship Is Going from Bad to Worse,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, March 7, 2016, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2016/03/malaysian-internet-censorship-going-bad-worse.

- 17Mong Palatino, “Malaysian Police Threaten Internet Users for Sharing Clown Memes of Prime Minister,” Advox, February 13, 2016, https://advox.globalvoices.org/2016/02/13/malaysian-police-threaten-internet-users-for-sharing-clown-memes-of-prime-minister/.

STAGE 4:

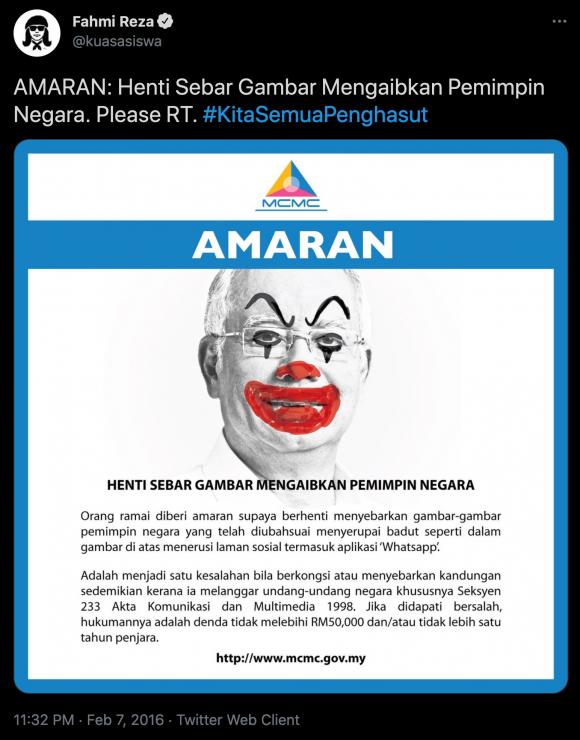

As the image spread across the internet and gained press coverage, the authorities ramped up their investigation against Fahmi Reza. Following the warning by the Malaysian police in January after his initial post on social media, Fahmi was served with a notice from the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) to remove his post on February 7th. As he did with the first warning, he turned the caution into a piece of satire by creating an edited version of an MCMC notice with the meme overlaid on top of it (figure 11 below). MCMC responded by issuing another warning to Fahmi and reiterated that he was still under investigation, stating, "We never released such advisories. Especially in such a manner. The fake notice which has been making its rounds since Saturday, depicted an edited photo of Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Tun Razak.”1

- 1Rahmah Ghazali, “MCMC to Investigate Clown Parody Notice,” The Star, February 9, 2016, https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2016/02/09/mcmc-to-investigate-clown-parody-notice.

Figure 11: Screenshot of Fahmi’s tweet in response to the take down notice he received from the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission. Tweet translation: “WARNING: Stop Spreading Images Disgracing National Leaders. Please RT. #WeAreAllSeditious.” Image translation: “WARNING: Stop Spreading Images Disgracing National Leaders. The public is warned against spreading edited pictures of the country's leaders in the form of clowns like the picture above on social media including through the Whatsapp application. It is an offence to share or spread such contents as it is against the laws especially Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act. If convicted, offenders will be fined a maximum of RM50,000 and/or a year's imprisonment.” Screenshot by TaSC.

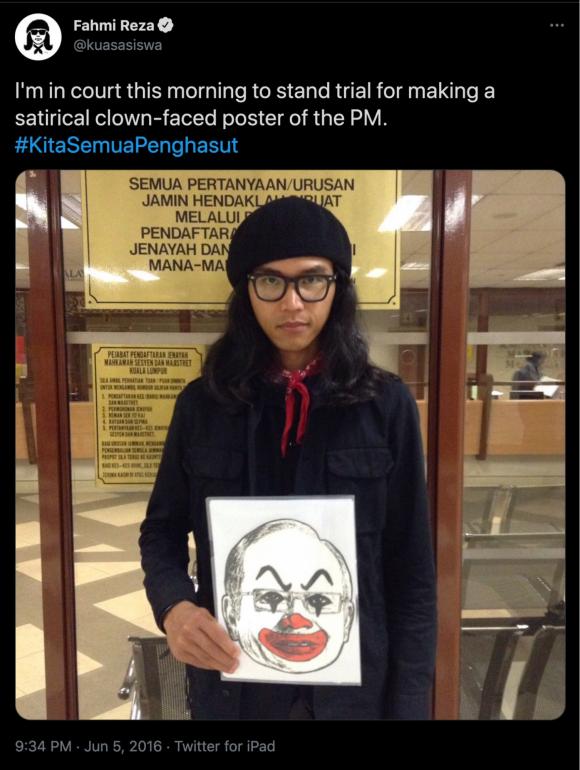

This attempt by the Malaysian government to contain the spread of the image again spurred more remixes and posts from Fahmi and others. As such, the authorities escalated the situation on June 4 by arresting him along with three others for selling t-shirts with the meme on it.1 On June 6, he was summoned to court to stand trial. Not wanting to waste another opportunity to share the image, he tweeted an image of himself with a print-out of the offending image (figure 12 below). On June 10, he was charged with two counts of violating the Communications and Multimedia Act, which criminalizes the creation and dissemination of content with an intent to "annoy, abuse, threaten, or harass."2 Fahmi pleaded not guilty. If found guilty, however, he would face jail time of up to a year, a fine of RM50,000 (approximately USD12,345 in 2016), or both.3 In addition, the police were investigating him for sedition. He was eventually released on bail on June 11.4

- 1M. Kumar, “Fahmi Reza, Three Others Arrested over #KitaSemuaPenghasut t-Shirts,” The Star, June 4, 2016, https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2016/06/04/fahmi-reza-two-others-sedition.

- 2“Malaysia: Fahmi Reza Sentenced to Prison and Fined,” Front Line Defenders, July 11, 2019, https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/en/case/fahmi-reza-sentenced-prison-and-fined; James Griffiths, “The Cartoonists Who Helped Take down a Malaysian Prime Minister,” CNN, May 28, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/style/article/malaysia-1mdb-najib-zunar-fahmi-reza-intl/index.html.

- 3“Malaysian Artist Fahmi Reza Charged for Depicting PM Najib as Clown,” The Straits Times, June 6, 2016, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/malaysian-artist-fahmi-reza-charged-for-depicting-pm-najib-as-clown.

- 4Fahmi Reza, “Aku dibebaskan dengan ikat jamin sementara menunggu masa untuk dibicara. Mengkritik penguasa korup dengan seni bukan satu kriminal. Punk adalah perlawanan. #KitaSemuaPenghasut #AktaSakitHati,” Facebook, June 10, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/login/?next=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2Fkuasasiswa%2Fposts%2F1030231313678969.

The arrest did not deter either Fahmi or other campaign participants from spreading the meme. Throughout the month of June, he continued posting on Facebook and Twitter iterations of the meme while speaking out against corruption and government overreach.1 On June 16, for example, he posted the following image and text (figure 13) explaining again why he chose to draw the image and what it means to him and to others who participate in its proliferation:

- 1Fahmi Reza, “Artikel 10 dalam Perlembagaan Persekutuan pada asasnya melindungi kebebasan dan hak asasi kita sebagai warganegara untuk bersuara dan berekspresi, termasuk menyuarakan kritikan dan ketidakpuasan hati kita kepada pemerintah.,” Facebook, June 21, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/login/?next=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2Fkuasasiswa%2Fposts%2F1036044493097651.

What’s more, the arrest did not stop mainstream media from resharing the image either. In an unusual turn of events, Utusan Malaysia, a media outlet owned by Barisan Nasional, the ruling coalition (and Najib’s coalition), published the story of his arrest in a straight-forward factual manner that outlined the events leading up to the arrest and the context without any of the expected anti-activist rhetoric. The article even included a photo of the offending meme. Fahmi posted a photo of the article on Facebook as an “Achievement Unlocked” post, noting “Today is one of the historic days of my life. For the first time in my 16-year history that I've been in the activism world, this is the first time my face came out in the Utusan Malaysia newspaper owned by the ruling party.” He continued to note that the reporting was fair and accurate and that they even included a link to his Instagram account, which, as Fahmi pointed out, “accidentally helped promote my Instagram account full of subversive pictures [translated].”1

“Secara tidak sengaja (atau sengaja), Utusan Malaysia telah membantu untuk menyebarkan gambar poster protes ini, dan ikut sama menghasut…. Nampaknya dalam negara yang penuh dengan korupsi, Utusan Malaysia pun jadi penghasut.”

Translation: “Inadvertently (or intentionally), Utusan Malaysia has helped to spread pictures of these protest posters, and joined in the incitement…. It seems that in a country full of corruption, Utusan Malaysia becomes an agitator.”

Although Fahmi was charged in 2016, he was not convicted until February 2018 for one of the charges. He was sentenced to one-month jail time and a RM30,000 fine by the Ipoh Sessions Court. He appealed the charge, and, although his jail time was postponed pending the appeal, he was forced to pay the fine immediately, which he crowdfunded within 18 hours.2 Eventually, one of the charges was dropped in October 2018,3 however, the second charge, which he filed an appeal against, was rejected on July 5, 2019.4 Throughout this time, images of the clown caricature continued to proliferate.

- 1Fahmi Reza, “Today is one of the historic days of my life. For the first time in my 16 year history I've been in the activism world, this is the first time my face came out in the utusan malaysia newspaper owned by the ruling party,” Facebook, June 7, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/login/?next=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2F100000763298189%2Fposts%2F1027836927251741%2F.

- 2“Fahmi Reza Raises RM30,000 in Just 18 Hours to Pay Court Fine,” Malay Mail, February 23, 2018, https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2018/02/23/fahmi-reza-raises-rm30000-in-just-18-hours-to-pay-court-fine/1584065.

- 3Nurbaiti Hamdan, “Fahmi Reza Acquitted over Najib Clown Sketch,” The Star, October 11, 2018, https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2018/10/11/fahmi-reza-acquitted-over-najib-clown-sketch.

- 4“Fahmi Reza Fails to Strike out Conviction for Publishing Najib Caricature,” The Star, July 5, 2019, https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2019/07/05/fahmi-reza-fails-to-strike-out-conviction-for-publishing-najib-caricature.

STAGE 5: Adjustments by Manipulators to New Environment

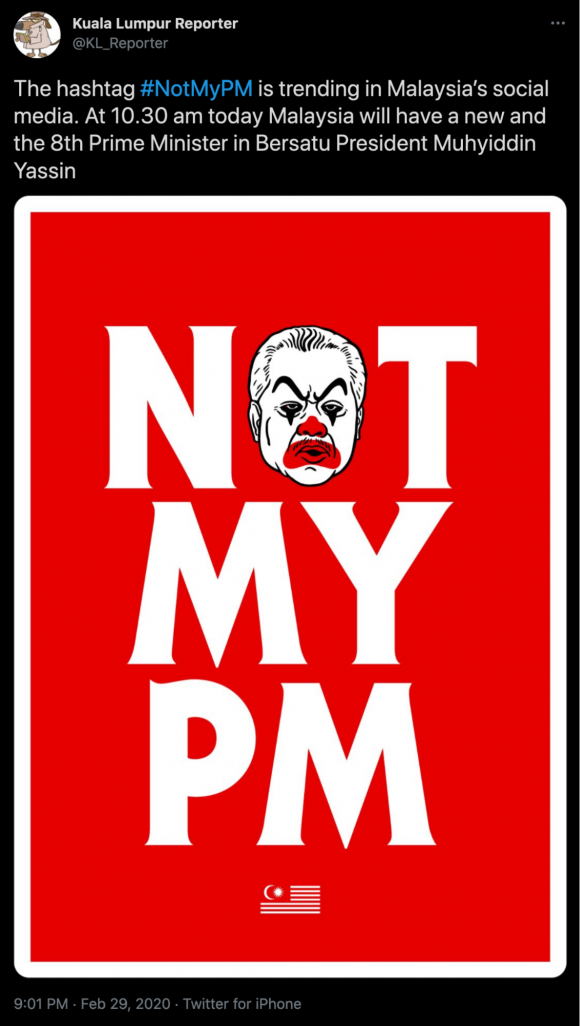

Despite his arrest in 2016, there was little success in mitigating the spread of the image. It continued to spread online and has since been redeployed for other political issues in Malaysia. In 2020 when Pakatan Harapan, the ruling coalition at the time who had previously ousted Barisan Nasional in a historic win in 2018, fell apart due to internal political divisions, a power grab triggered a new coalition to form under the now Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin. Because there was no election, however, Muhyiddin was seen by many as an illegitimate leader. #NotMyPM became a hashtag campaign on Twitter, reaching trending status on February 29, 2020 after his appointment was announced.1 The clown-faced imagery was repurposed but instead of Najib, the caricature was of Muhyiddin (see figure 14 below). Fahmi also joined in on the remixing.2

Despite the practical difficulties in censoring content on the internet, arrests in Malaysia using the Sedition Act and the Communications and Multimedia Act continue at time of writing. Most recently, on April 24, 2021, Fahmi was arrested by the police for a Spotify playlist that was deemed insulting to Malaysian royalty. Though the graphic artist knew it would provoke a strong reaction, he did not anticipate 20 police officers kicking a hole in his wall, barging in, seizing his laptop and phone, and leading him away in handcuffs.3 After one day in jail, he was released on bail.4 Unlike his posts on Twitter and Facebook, Spotify did comply with the Malaysian government’s wishes and removed the playlist repeatedly as Fahmi continuously tried to reupload the playlist.

- 1Amy (@1AmyChew) Chew, “#NotMyPm has trended to the top of Malaysia Twitter following the announcement of the appointment of Muhyiddin Yassin as the 8th Prime Minister of #Malaysia,” Twitter, February 29, 2020, https://twitter.com/1amychew/status/1233708676474494977.

- 2Fahmi (@kuasasiswa) Reza, “#NotMyPM,” Twitter, March 11, 2020, https://twitter.com/kuasasiswa/status/1237666371153973249.

- 3Heather Chen, “Malaysia’s Fahmi Reza Speaks Out About His Arrest and Being ‘Censored’ by Spotify,” Vice, April 27, 2021, https://www.vice.com/en/article/epndzw/malaysia-fahmi-reza-spotify-queen.

- 4Heather Chen, “Malaysia’s Fahmi Reza Speaks Out About His Arrest and Being ‘Censored’ by Spotify.”

Discussion

This was not the first time nor the last that Malaysia arrested and charged artists for their work. Previously, Zunar, a Malaysian cartoonist was banned from leaving the country, his works confiscated and banned, and was charged with sedition.1 In another case, Lena Hendry, a filmmaker, was charged under the Film Censorship Act after she organised a screening of a documentary about human rights violations in Sri Lanka.2 This is not an isolated phenomenon targeting just artists, however. Throughout the country’s history, opposition politicians and journalists have also been subjected to censorship and intimidation.

, therefore, becomes an important and often effective means of circumventing oppressive regimes of information control and gatekeeping. In such cases, “sowing ” and even distrust may not necessarily be detrimental to democracy, but rather, a much needed intervention. Attempts to game algorithms, bait journalists, and elicit reactions from mainstream press, the government, and other political and media elites—all acts of —can become a means to shed light on important issues, advocate for vulnerable communities, and seek redress in an otherwise skewed media ecosystem where only the wealthy and powerful have a voice.

This case study also points to the difficulty in mitigating the harms of , misinformation, and other information-based threats. The very same networks, tactics, and strategies common to disinformation campaigns are also used by civil society. Any policy proposals must therefore contend with the tension between protecting freedom of expression and protection from false information. The Malaysian Anti-Fake News Act that was enacted in 2018 mere months before the historic 14th General Election where Barisan Nasional and Najib lost (a first for the political coalition, which governed Malaysia since its independence from the British), is an example of how legislation can be manipulated for political means. Speaking to the press, then Deputy Communications and Multimedia Minister Jailani Johari called all unverified information pertaining to 1MDB “fake news,” and accused foreign news outlets reporting on 1MDB of peddling “fake news” in a bid to tarnish Najib ahead of the election.3

Journalists, media outlets, and activists were rightly worried that the Anti-Fake News Act would be used to silence criticism of the government.4

Fortunately, the law was eventually repealed after considerable outcry. However, censorship, arrests, and state-backed intimidation over online content still continue under existing laws, such as the Sedition Act and the Communications and Multimedia Act. In 2020, for example, Malaysia’s most prominent independent news outlet, Malaysiakini, was found to be legally responsible for five reader comments deemed insulting to the judiciary and ordered to pay a fine of nearly US$124,000.5 Steven Gan, the editor and co-founder of Malaysiakin, who was previously acquitted of the same charge, was disappointed with the verdict:

“What crime has Malaysiakini committed that we are forced to pay 500,000 when there are individuals charged with abuse of power for millions and billions who are walking free?”

Fortunately, Malaysiakini was able to fundraise the fine within hours.6 Like Fahmi, they continue to be an outspoken voice in Malaysia, despite threats of censorship and jail.

- 1James Griffiths, “The Cartoonists Who Helped Take down a Malaysian Prime Minister.”

- 2“Malaysia – Human Rights Defender Lena Hendry Convicted,” Front Line Defenders, December 14, 2017, https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/en/case/case-history-lena-hendry.

- 3“Malaysia’s Deputy Minister Warns Foreign Media against Spreading ‘fake News’ about 1MDB,” The Straits Times, March 11, 2018, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/malaysias-deputy-minister-warns-foreign-media-against-spreading-fake-news-about-1mdb.

- 4Gabrielle Lim, “SECURITIZE/ COUNTER-SECURITIZE: The Life and Death of Malaysia’s Anti-Fake News Act” (Data & Society, n.d.), https://datasociety.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Securitize-Counter-securitize.pdf.

- 5Richard C. Paddock, “5 Reader Comments Just Cost a News Website $124,000,” The New York Times, February 19, 2021, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/19/world/asia/malaysia-press-freedom-guilty.html.

- 6“Malaysiakini Exceeds RM500k Fundraising Target for Hefty Court Fine,” Malaysiakini, February 19, 2021, https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/563603.

Cite this case study

Gabrielle Lim, "#WeAreAllSeditious: Malaysian Activists and the Meme War Against Corruption," The Media Manipulation Case Book, June 13, 2022, https://casebook-static.pages.dev/case-studies/weareallseditious-malaysian-activists-and-meme-war-against-corruption.